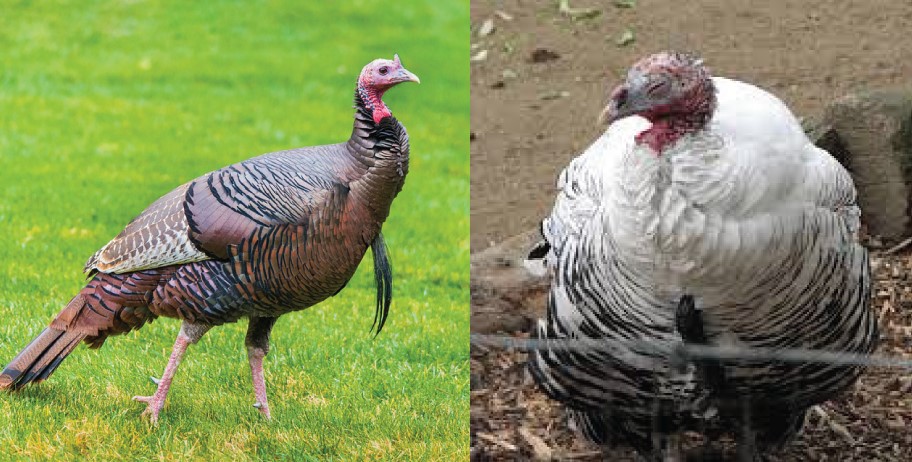

SCORES & OUTDOORS – The Thanksgiving turkey: wild vs. domesticated

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

Thanksgiving is here again, and is the unofficial kick off point for the holiday season. Turkeys are the main fare at the dinner table on that day. So what do we know about the wild gobbler?

The wild turkey (Meleagris gallopavo) is an upland ground bird native to North America. Although native to North America, the turkey probably got its name from the domesticated variety being imported to Britain in ships coming from the Levant via Spain. The British at the time, therefore, associated the wild turkey with the country Turkey and the name prevails.

Wild turkeys prefer hardwood and mixed conifer-hardwood forests with scattered openings such as pastures, fields, orchards and seasonal marshes. They seemingly can adapt to virtually any dense native plant community as long as coverage and openings are widely available.

Despite their weight, wild turkeys, unlike their domesticated counterparts, are agile, fast fliers. In ideal habitat of open woodland or wooded grasslands, they may fly beneath the canopy top and find perches. They usually fly close to the ground for no more than a quarter mile.

Wild turkeys have very good eyesight, but their vision is very poor at night. They will not see a predator until it is too late. At twilight most turkeys will head for the trees and roost well off the ground; it is safer to sleep here in numbers than to risk being victim to predators who hunt by night. Because wild turkeys don’t migrate, in snowier parts of the species’s habitat like the Northeast, it is very important for this bird to learn to select large conifer trees where they can fly onto the branches and shelter from blizzards.

Wild turkeys are omnivorous, foraging on the ground or climbing shrubs and small trees to feed. They prefer eating acorns, nuts and other hard mast of various trees, including hazel, chestnut, hickory, and pinyon pine as well as various seeds, berries such as juniper and bearberry, roots and insects. Turkeys also occasionally consume amphibians and small reptiles such as lizards and small snakes.

Turkey populations can reach large numbers in small areas because of their ability to forage for different types of food. Early morning and late afternoon are the desired times for eating.

Males are polygamous, mating with as many hens as they can. Male wild turkeys display for females by puffing out their feathers, spreading out their tails and dragging their wings. This behavior is most commonly referred to as strutting.

Predators of eggs and nestlings include raccoons, striped skunks, groundhogs, and other rodents. Avian predators of poults include raptors such as bald eagles, barred owl, and Harris’s hawks, and even the smallish Cooper’s hawk and broad-winged hawk.

Predators of both adults and poults include coyotes, gray wolves, bobcats, cougars, Canadian lynx, golden eagles and possibly American black bears

Occasionally, if cornered, adult turkeys may try to fight off predators, and large male toms can be especially aggressive in self-defense. When fighting off predators, turkeys may kick with their legs, using the spurs on their back of the legs as a weapon, bite with their beak and ram with their relatively large bodies and may be able to deter predators up to the size of mid-sized mammals. Occasionally, turkeys may behave aggressively towards humans, especially in areas where natural habitats are scarce. They also have been seen to chase off humans as well. However, attacks can usually be deterred and minor injuries can be avoided by giving turkeys a respectful amount of space and keeping outdoor spaces clean and undisturbed. Male toms occasionally will attack parked cars and reflective surfaces thinking they see another turkey and must defend their territory. Usually a car engine and moving the car is enough to scare it off.

At the beginning of the 20th century the range and numbers of wild turkeys had plummeted due to hunting and loss of habitat. When Europeans arrived in the New World, they were found from Canada to Mexico in the millions. Europeans and their successors knew nothing about the life cycle of the bird and ecology, itself, as a science would come too late, not even in its infancy, until the end of the 19th century whereas heavy hunting began in the 17th century. Deforestation destroyed trees turkeys need to roost in.

Game managers estimate that the entire population of wild turkeys in the United States was as low as 30,000 by the late 1930s. By the 1940s, it was almost totally extirpated from Canada and had become localized in pockets in the United States. In the northeast they were restricted to the Appalachians, only as far north as central Pennsylvania. Early attempts used hand reared birds, a practice that failed miserably as the birds were unable to survive.

Wild turkeys were once native to Maine but were extirpated in the early 1800s from overhunting and the clearing of forests along the coast. But in 1978, wild turkey were successfully reintroduced in Maine by state biologists – and the birds have thrived since.

But not everybody is so enthusiastic about the state’s success in reintroducing wild turkeys, which began back in the 1970s in York County. In fact, plenty of Mainers think we have far too many turkeys on the landscape and blame the birds for a variety of ills.

In some parts of the state, there are a lot of turkeys. And though the state deals with few calls about nuisance turkeys, there are places where efforts to limit the number of birds might make sense.

However, these big birds get a bum rap and are blamed for a variety of problems. If you see a flock of turkeys in a blueberry field at noontime, you might blame the birds for eating all the berries. But there are deer, bear, moose, foxes and other critters in that blueberry field at night, doing damage.

Do we have too many turkeys?

It all depends on whether the birds are eating your crops, or foiling your attempts to hunt them.

Had it been up to Benjamin Franklin, the turkey we carve for Thanksgiving dinner might have been our national bird. After the bald eagle won the honor instead, Franklin wrote to his daughter that the turkey was “more respectable” than the eagle, which he thought was “of bad moral character,” calling them lazy, opportunistic predators.

Franklin expressed admiration for the feisty way barnyard turkeys defended their territory, a trait he liked in Americans, too. It’s not clear, however, whether Franklin knew much about wild turkeys, which ran and hid from intruders instead of defending their turf. Indeed, some Apache Indians thought turkeys were so cowardly that they wouldn’t eat them or wear their feathers for fear of contracting the spirit of cowardice.

So Franklin probably wasn’t thinking about the wild turkey when he considered possible symbols of American courage. But the domestic or barnyard turkey he admired did have its origins in America’s wild turkey population.

Aztec Indian tribes had long domesticated wild turkeys for food. Early Spanish explorers discovered these domesticated turkeys and took a few of them back to Europe, where the birds were bred into yet another variety of domestic turkey.

Those European turkeys came to North America with English colonists and were used for food. They are the birds Franklin seems to have preferred over the native bald eagle for our national symbol.

So, even though the bald eagle is the official bird of the United States, much to the chagrin of Benjamin Franklin, it must be pointed out that on Thanksgiving day, the wild turkey is the national “bird of the day,” even though most of us actually consume domesticated turkeys.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

The Buffalo Bills appeared in four consecutive Super Bowls from 1990-1993. Have there ever been teams to appear in three in a row?