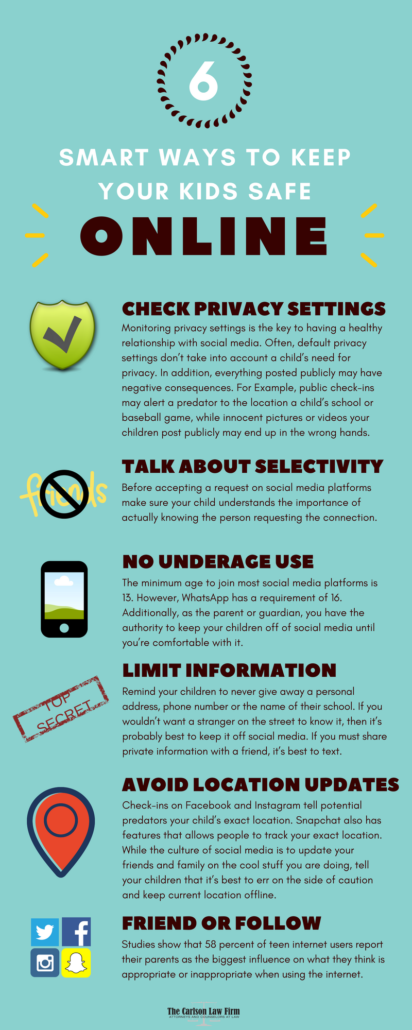

ERIC’S TECH TALK – Deepfake: When you can’t believe your eyes

A screenshot from the fake Obama video created by researchers at the University of Washington.

by Eric W. Austin

by Eric W. Austin

Fake news. Fake videos. Fake photos. The way things are heading, the 21st century is likely to be known as the Fake Century, and it’s only going to get worse from here.

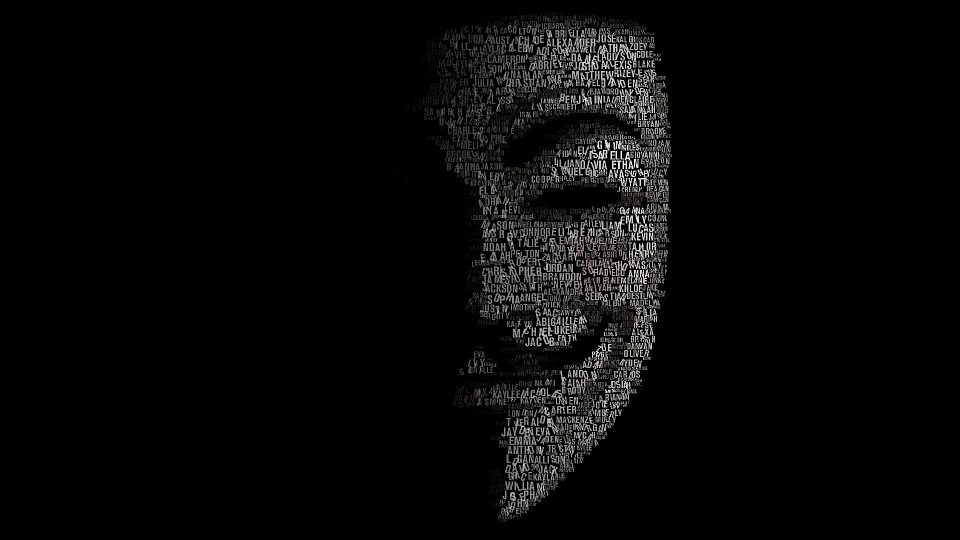

About a year ago, I came across a short BBC News report. It talked about an initiative by researchers at the University of Washington to create a hyper-realistic video of President Obama saying things he never said. On Youtube, they posted a clip of the real Obama alongside the fake Obama the researchers had created. I couldn’t tell the difference.

Welcome to the deepfake future.

“Deepfake” is probably not a term you’ve heard a lot about up ‘til now, but expect that to change over the next few years. The term is derived from the technology driving it, deep learning, a branch of artificial intelligence emphasizing machine learning through the use of neural networks and other advanced techniques. When Facebook tags you in a photo uploaded by a friend, that’s an example of deep learning in action. It’s an effort to replicate human-like information processing in a computer.

Artificial intelligence is not just getting good at recognizing human faces; it’s becoming good at creating them, too. By feeding an A.I. thousands of images or video of someone, for example a public figure, the computer can then use that information to create a new image or video of the person that is nearly indistinguishable from the real thing.

Of course, this sort of fakery has been around for a long time in photography. Do an unfiltered Google image search for any attractive female celebrity, and you’re likely to find a few pictures with the celebrity’s head photoshopped onto the body of a porn actress in a compromising position. Search for images of UFOs or the Lock Ness Monster, and you’ll find dozens of fake photos, many of which successfully fooled the experts for years.

But what we’re talking about here is on a completely different level. Last year I wrote about a new advancement in artificial intelligence allowing a computer to mimic the voice of a real person. Feed the computer 60 seconds of someone speaking and that computer can re-create their voice saying absolutely anything you like.

Deepfake is the culmination of these two technologies, and when audio and video can be faked convincingly using a computer algorithm, what hope is there for truth in the wild world of the web?

If the past couple years have taught us anything, it’s that there are deep partisan divides in this country and each side has a different version of the truth. It’s not so much a battle of political parties as it is combat between contrasting narratives. It’s a war for belief.

Conspiracy theories have flourished in this environment, as each side of the debate is all too willing to believe the worst of the other side — whether it’s true or not. I have written several times about the methods Russia and others have used to influence the U.S. electorate, but it’s this willingness to believe the worst about our fellow Americans that is most often exploited by our adversaries.

Communist dictator Joseph Stalin was infamous for destroying records and altering images to remove people from history after they had fallen out of favor with him.

Likewise, when the Roman sect of Christianity gained ascendancy in the early 4th century CE, they set about destroying the gospels held sacred by other groups. This was done in order to paint the picture of a consistently unified church without divisions (“catholic” is Latin for “universal”).

In both these cases, narratives were shaped by eliminating any information that contradicted the approved version of events. However, with the advent of the Internet and a mostly literate population, that method of controlling the narrative just isn’t possible anymore. Instead, the technique has been adjusted to one which floods the public space with so much false and misleading information that even intelligent, well-meaning people have trouble telling the difference between fact and fiction.

If, as Thomas Jefferson once wrote, a well-informed electorate is a prerequisite to a successful democracy, these three elements – our willingness to believe the worst of our political opponents, the recent trend of controlling the narrative by flooding the public consciousness with misinformation to obscure the truth, and the advancements of technology allowing this fakery to flourish and spread – are combining to create a challenge to our republic like nothing we’ve experienced before.

What can you do about the coming deepfake flood? Let me give you some advice I take myself: Make sure you rely on a range of diverse and credible sources. Regularly read sources with a bias different from your own, and stay away from those on the extreme edges of the political divide. Consult websites like AllSides.com or MediaBiasFactCheck.com to see where your favorite news source falls on the political spectrum.

We have entered the era of post-truth politics, but that doesn’t mean we have to lose our way in the Internet’s labyrinth of lies. It means we need to develop a new set of skills to navigate the environment in which we now find ourselves.

The truth hasn’t gone away. It’s just lost in a where’s Waldo world of obfuscation. Search hard enough, and you’ll see it’s still there.

Eric W. Austin writes about technology and community issues. He can be reached by email at ericwaustin@gmail.com.

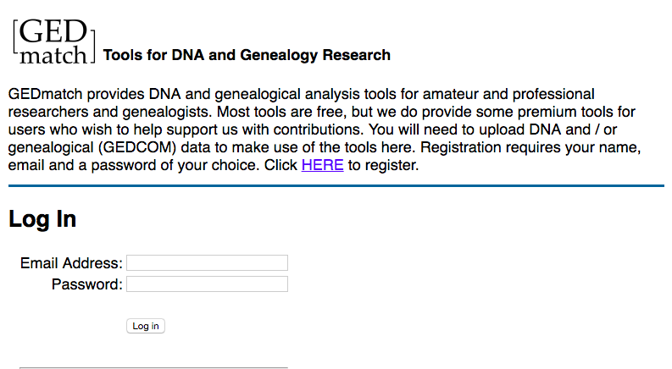

This is the service investigators used to finally track down the Golden State Killer. The suspect hadn’t uploaded his own genetic profile to the database, but distant relatives of his had. Once the investigation could identify individuals related – however distantly – to the suspect, it took only four months to narrow their search down to the one person responsible. Then it was a simple exercise of obtaining a DNA sample from some trash the suspect discarded and matching it to samples from the original crime scenes.

This is the service investigators used to finally track down the Golden State Killer. The suspect hadn’t uploaded his own genetic profile to the database, but distant relatives of his had. Once the investigation could identify individuals related – however distantly – to the suspect, it took only four months to narrow their search down to the one person responsible. Then it was a simple exercise of obtaining a DNA sample from some trash the suspect discarded and matching it to samples from the original crime scenes. The availability of genetic testing for the average consumer was just a distant dream when HIPAA passed in 1996. The internet was still in its infancy. A lot has changed in the last 22 years, and our laws have not kept up.

The availability of genetic testing for the average consumer was just a distant dream when HIPAA passed in 1996. The internet was still in its infancy. A lot has changed in the last 22 years, and our laws have not kept up.

For small papers like The Town Line, which offers the paper for free and receives little income from subscriptions, this is an especially hard blow: more people are reading the paper, and there’s a great demand for content, but there is also less income from advertising to cover operating costs.

For small papers like The Town Line, which offers the paper for free and receives little income from subscriptions, this is an especially hard blow: more people are reading the paper, and there’s a great demand for content, but there is also less income from advertising to cover operating costs.