Effort underway to improve cottontail habitat

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

I was encouraged to hear recently of the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife’s renewed effort to create more habitat for the New England Cottontail.

New England cottontails, Sylvilagus transitionalis, were once a common sight along the coast, but as old fields turned to forest, and farmland became developed, habitat for this distinctively New England species diminished and their numbers declined. New England cottontails need shrub lands and young forests to thrive.

At one time, the New England cottontail was the only rabbit east of the Hudson River, until the Eastern cottontail was introduced in the late 1800s.

Until the 1950s, the New England cottontail was considered the more abundant species in New England. By the 1960s, biologists noticed that the Eastern cottontail was replacing the New England cottontail throughout New England.

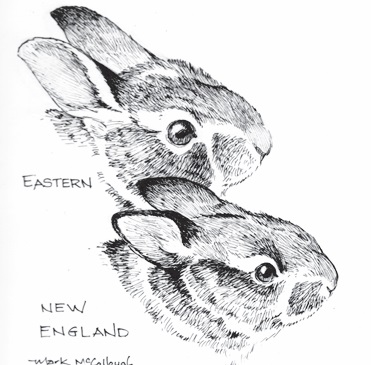

New England Cottontail

Today, the Eastern cottontail is far more abundant, except in Maine, where the New England cottontail remains the only rabbit. But, it is confined to southern Maine. It is still found in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and New York, however, the species range had been reduced by more than 80 percent by 1960. Today, the New England cottontail’s range is 86 percent less. The numbers are going in the wrong direction.

Because of this decline in numbers, the New England cottontail is a candidate for protection under the Endangered Species Act. Cottontail hunting has been restricted in some areas where the Eastern and New England cottontails coexist in order to protect the New England cottontail populations.

According to at least one study the cottontails’ historic range also included a small part of southern Québec, from which it is extirpated.

In order to merely survive, a single New England cottontail requires at least two-and-a-half acres of suitable habitat. For long-term security and persistence, 10 rabbits need at least 25 acres. Over the last 100 years, forests throughout New England have aged. As shade from the canopy of mature trees increases, understory vegetation thins and no longer provides sufficient New England cottontail habitat.

Eastern Top, New England below

It’s not easy to distinguish the difference between Eastern and New England cottontails. The New England cottontail has shorter ears, slightly smaller body size, a black line on the anterior edge of the ears, a black spot between the ears and no white spot on the forehead. The skulls of the two species are also quite different and are a reliable means of distinguishing the two.

The major factor in the decline of the New England cottontails is habitat destruction from the reduced thicket habitat. Before Europeans settled, the New England cottontails were likely found along river valleys, where disturbances in the forest, such as beaver activity, ice storms, hurricanes and wildfires promoted thicket growth. Development has eliminated a large portion of that habitat.

However, there are other factors in the equation:

- The introduction of more than 200,000 Eastern cottontails, mostly by hunting clubs, greatly harmed the New England cottontail because the Eastern cottontails are more diverse in their diet. They also have a slightly better ability to avoid predators. Known predators of the New England cottontail include birds of prey, coyotes, Canadian lynx and bobcats. To avoid predators, New England cottontails run for cover, “freeze” and rely on their cryptic coloration; or, when running, follow a zig-zag pattern to confuse the predator. Because New England cottontail habitat is small and has less vegetative cover, they must forage more often in the open, leaving them vulnerable.

- The introduction of invasive plant species such as multiflora rose, honeysuckle bush anbd autumn olive in the 20th century may have displaced many native species that provided food for the New England cottontails.

- An increase in population and density of white-tailed deer in the same range as the New England cottontails also damaged populations, because deer eat many of the same plants and damage the density of understory plants providing vital thicket habitat.

That’s why the plan to create more habitat for the New England cottontail in the Scarborough Marsh Wildlife Management Area is a step in the right direction to restore the species to its historic numbers.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!