SCORES & OUTDOORS: In case you hadn’t noticed, tick season has already arrived in central Maine

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

It’s the time of year when you start to hear horror stories about deer ticks. I have already heard more than I really want to this early.

People have told me about letting their dogs out, only to come back covered in ticks. My granddaughter’s husband told me he went to cut up some downed trees, and came home to pick 10 ticks off himself. Neighbors at camp are all bundled up as they do outdoor clean up. Long-sleeved shirts, sweatshirts, pants tucked into socks. Not exactly what I would call a fashion show, especially when they are wearing striped socks.

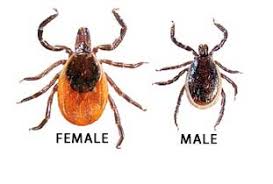

The deer tick’s actual name is black-legged tick, Ixodes scapularus.

It is all too well known that the deer tick can transmit the painful Lyme disease, but can also pass on anaplasmosis, babesiosis, deer tick virus encephalitis, and a relapsing fever illness caused by a different spirochete spiral-shaped bacteria.

Deer ticks first appeared in Maine in the southern counties in the 1980s. They advanced along the coast and then found their way inland. It can now be encountered in northern Maine. They are prominent in mixed forests and along the woodland edges of fields and suburban landscapes. They are present nationally throughout northeast and in north-central states. They are present in the south, but because they feed primarily on non-infectious hosts there, Lyme disease is far less common.

A mated adult female deer tick, after having obtained a blood meal from a white-tailed deer, dog, cat or other large mammal in the fall or early spring, can lay as many as 3,000 eggs in late May and early June. Uninfected larvae emerge in mid-summer and soon seek a blood meal, primarily from mice, other small mammals and certain songbirds. Many of the animals they feed on, particularly mice and chipmunks, will have been previously infected with Lyme, and other tick-borne diseases; it is from these “reservoir hosts” that deer ticks become infected.

A mated adult female deer tick, after having obtained a blood meal from a white-tailed deer, dog, cat or other large mammal in the fall or early spring, can lay as many as 3,000 eggs in late May and early June. Uninfected larvae emerge in mid-summer and soon seek a blood meal, primarily from mice, other small mammals and certain songbirds. Many of the animals they feed on, particularly mice and chipmunks, will have been previously infected with Lyme, and other tick-borne diseases; it is from these “reservoir hosts” that deer ticks become infected.

After over-wintering, larvae molt to nymphs which seek a second blood meal in the spring, passing on the infections they acquired as larvae to the next year’s crop of small mammal/avian hosts.

Nymphs may also feed on humans, dogs and horses, and other hosts. Their tiny size and painless bites may allow them to remain undetected through the approximately 36 hours it takes for the infection to be transmitted from a feeding tick. Once they’ve had their fill of blood, deer tick nymphs drop to the leaf litter, and in early fall molt to adult males and females.

Most human Lyme disease results from the bite of undiscovered nymphs in the summer. In Maine, nymphs peak in late June and July, which is when approximately 65 percent of the human cases of Lyme disease are reported. Dogs and other domestic animals are more frequently infected in the fall and spring by adult ticks which escape detection.

The life cycle of a deer tick generally lasts two years. During this time, they go through four life stages: eggs, six-legged larva, eight-legged nymph, and adult. Once they hatch, they must have a blood meal at every stage to survived.

Ticks can’t fly or jump, instead they wait for a host, resting on the tips of grasses and shrubs in a position known as “questing.” While questing, ticks hold onto leaves and grass by their lower legs. They hold their upper pair of legs outstretched waiting to climb onto a passing host. When a host brushes the spot where a tick is waiting, it quickly climbs aboard. It then finds a suitable place to bite its host.

Depending on the tick species and its life stage, preparing to feed can take from 10 minutes to two hours. When the tick finds a feeding spot, it grasps the skin and cuts into the surface. The tick then inserts its feeding tube. Many species also secrete a cement-like substance that keeps them firmly attached. Some have barbs which help keep the tick in place. Ticks also secrete a small amount of saliva with anesthetic properties so the animal or person can’t feel that the tick has attached itself. If the tick is in a sheltered spot, usually around the hairline, it can go undetected.

If the host animal has certain blood-borne infections, such as the Lyme disease agent, the tick may ingest the pathogen and become infected, then in turn, later feeds on a human, that human can become infected.

Following the feeding, the tick drops off and prepares for the next life stage. At its next feeding, it can then transmit the infection to the new host. Once infected, a tick can transmit infection throughout its life.

Removing the tick quickly, within 24 hours, can greatly reduce your chances of getting Lyme disease. It takes time for the tick to transmit the infection, so the longer the tick is attached, the more chances a human is of contracting Lyme disease.

Over the years, I have been fortunate to have dealt with only four deer ticks, especially where I spend so much time outdoors. For the first one I went to the emergency room to have it removed. The other three were quickly dispatched upon discovering them. If you spend a lot of time outdoors, it is wise to do a complete check once you move indoors. It’s never too early to pull off a deer tick once it is found.

Information for this column was acquired from the Maine Medical Center Research Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Which boxer inflicted Muhammad Ali’s first defeat in professional boxing?

FLYING SQUIRREL: A couple of weeks ago I wrote about flying squirrels in Maine. Their existence was confirmed by Kimberly Chase Hutchinson who shared this photo with the comment, “Yup, had one in my Christmas tree this past Christmas.”

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!