Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Trolleys

by Mary Grow

Not long after finishing the piece about street railways that appeared in The Town Line, Sept. 10, this writer came across a small paperback book published in 1955. Written by O. R. (Osmond Richard) Cummings, it is titled Toonervilles of Maine, the Pine Tree State.

(The title refers to Fontaine Fox’s comic strip called Toonerville Folks that Wikipedia says first appeared in the Chicago Post in 1908 and last appeared in 1955. Toonerville was a suburban community with an assortment of oddball characters. One was Terrible-Tempered Mister Bang, who drove the Toonerville Trolley that met all the trains, Wikipedia explains.)

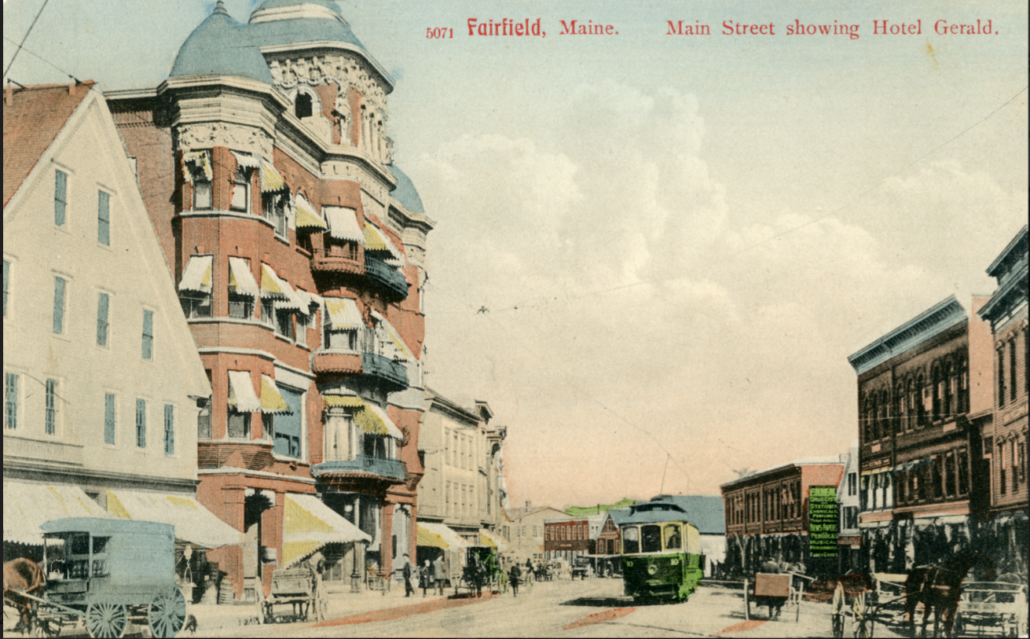

Additionally, the Connecticut Valley Chapter of the National Railway Historical Society’s April-December 1965 Transportation Bulletin, available on line, includes a well-illustrated article Cummings wrote about the Waterville & Fairfield and other area street railways. Cummings and the Fairfield history both have information on trolleys in Fairfield, but they do not always agree. Cummings’ work is much more detailed, with information from multiple historical records.

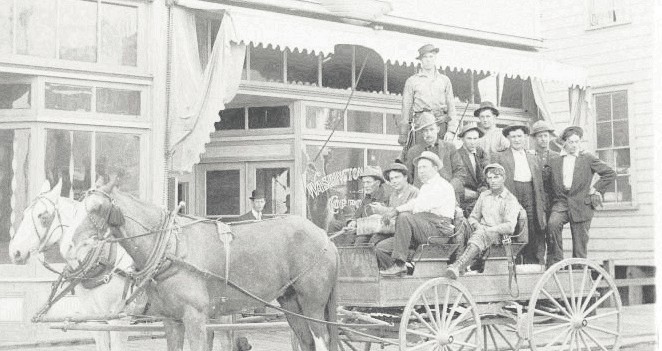

The Waterville & Fairfield Railroad, which was initially powered by horses, is described in both books. Cummings wrote that it was incorporated on Feb. 24, 1887, and authorized to run horse-drawn cars the three and a third miles from Waterville to Fairfield. With $20,000 in bond sales and $20,000 borrowed, Amos F. Gerald, of Fairfield, and the other organizers acquired four cars and six horses. They oversaw the laying of tracks along the west side of the Kennebec roughly where College Avenue now runs and construction of a wooden carhouse for the cars and stable for the horses in Fairfield.

One online photo shows an elaborate open passenger car, rather precariously balanced on two sets of small wheels under its middle third, drawn by two white horses. Two women in floor-length skirts stand on the sidewalk in front of a row of large-windowed two-story brick buildings on Main Street, in Fairfield. The car is identified as Horse Car No. 1, and the estimated date is opening day, June 23, 1888 (the Fairfield historians wrote that service began June 24, 1888).

Cummings said the open cars had eight benches and could accommodate 40 passengers. Another photo shows a closed car outside the Fairfield carhouse; the closed cars had space for 20 passengers, according to the text.

The railway soon had 24 horses. The Railroad Commissioners’ 1889 report, quoted by Cummings, said the horses “are well fed and kindly treated.”

The Waterville & Fairfield was well-patronized, Cummings wrote, carrying almost 95,000 passengers between its June 1888 opening and Sept. 30 that year. In its first full year, Sept. 30, 1888, to Sept. 30, 1889, there were 232,684 passengers, and despite having to buy snow-moving equipment and repair tracks in the spring, the line made a profit: $657, of which stockholders got $600 as dividends.

The next two years saw deficits almost $1,400. Nonetheless, early in 1891 two things happened indicating the railway was considered a going concern.

First, Cummings wrote, Gerald and other local men organized the Waterville & Fairfield Railway & Light Company, chartered by the Maine legislature on Feb. 12 and approved to buy the Waterville & Fairfield and two electric companies, in Waterville and Fairfield. The two railway companies became one on July 1, 1891.

The second event was that on March 4, the legislature authorized the Waterville & Fairfield to build a line through Winslow to North Vassalboro and to become an electric railroad.

The next year, horses were replaced by electricity, a conversion that involved adding poles and overhead wires, large generators at both ends of the line and new equipment in the cars. The first electric cars ran July 20, 1892. Cummings wrote that residents were excited and every car was full on opening day.

13-bench open car #11 of the Waterville, Fairfield & Oakland Railway, with conductor William McAuley, standing left, and motorman John Carl, on Grove St., in Waterville, near Pine Grove Cemetery.

The Waterville & Fairfield was the first of several street railways serving the area from the late 19th century well into the 20th century. Another that the Fairfield history describes was the Benton & Benton Falls Electric Railroad. It opened Dec. 7, 1898, and extended its tracks to Fairfield in July 1900. Cummings wrote about the Benton & Fairfield Railway, which had been operating a shorter line before it connected Benton to Fairfield in 1901. (The writer suspects the two were the same, perhaps going by slightly different names and owners’ names at different times.)

The Benton & Fairfield, Cummings wrote, was owned by Kennebec Fibre Company and served primarily to carry pulpwood delivered on Maine Central freight cars to Benton and Fairfield paper mills. Its first three miles of track, all in Benton, opened Dec. 7, 1898. Extensions in 1899 and 1900 brought the line across the Kennebec to Fairfield and increased mileage to a little over four miles.

Cummings wrote that the railroad made a profit in only nine of its 32 or so years, and state railway commissioners were frequently dissatisfied with its maintenance. What little passenger service was offered ended in 1928, and the railroad went out of business around 1930, Cummings found.

The Fairfield & Shawmut connected those two villages in 1906 (Fairfield history) or October 1907 (Cummings). Amos Gerald was among its founders. It was primarily intended to serve passengers; Cummings wrote that its schedules were designed to let people transfer to the Waterville & Fairfield. The fare was five cents; the three-mile trip took 15 minutes, and cars ran every half hour.

The line, a little more than three miles long, served Keyes Fibre Company near Shawmut and Central Maine Sanatorium on Mountain Avenue between downtown Fairfield and Shawmut. There was a waiting room for sanatorium visitors at the foot of the avenue, Cummings wrote.

Like the other electric railroads Cummings described, the Fairfield & Shawmut was partly built with borrowed money — $30,000, in this case. Cum—mings wrote that when the 20-year bonds came due July 1, 1927, there wasn’t enough money to redeem them. The bondholders chose a receiver who got approval to abandon the railroad; the last trolleys ran July 23, 1927.

The Waterville & Fairfield met the lines from Benton and from Shawmut in Fairfield, and provided electricity for both.

As the Waterville & Fairfield grew, local businessmen formed the Waterville & Oakland Street Railway. (Yes, one was Amos F. Gerald, and Cummings lists him as the railway’s first general manager.) It was chartered in 1902, despite opposition from the Maine Central Railroad that also connected the two towns. Construction began in April 1903; the line from downtown Waterville to Snow Pond opened July 2, 1903, Cummings wrote.

High trestle over the Messalonskee Stream, in Oakland, with one of the Duplex convertibles crossing at the Cascade Woolen Mill.

The new line required two bridges across Messalonskee Stream, one in Oakland and one off Western Avenue in Waterville. The railway and the city split the cost of the Waterville bridge, which Cummings said was 53 feet long and 28 feet wide.

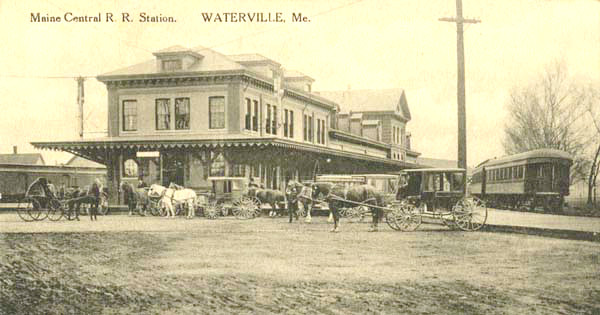

The Waterville & Fairfield and Waterville & Oakland met in Waterville. Thence passengers could travel to Fairfield and connect for Benton or Shawmut.

By 1910, the Waterville & Fairfield tracks had been extended into the southern part of Waterville, out Grove Street to Pine Grove Cemetery and out Silver Street. There might have been a plan to connect the two lines at the foot of what is now Kennedy Memorial Drive; if so, it was never achieved.

The Waterville & Fairfield and Waterville & Oakland consolidated in 1911 under the auspices of Central Maine Power Company (which owned two other street railways in Maine). As of December of that year, Cummings wrote, the new Waterville, Fairfield & Oakland had 10.5 miles of track plus sidings.

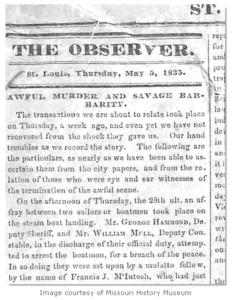

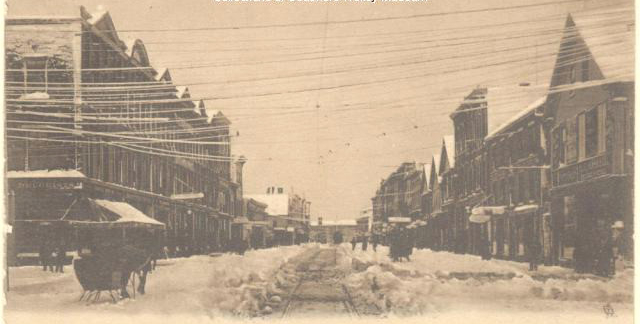

A postcard showing Main St., in Waterville, after an ice storm with iced lines and plowed Waterville, Fairfield & Oakland trolley tracks running the middle of the street, on March 10, 1906.

The line through Winslow and Vassalboro was eventually built by the Lewiston, Augusta & Waterville Street Railway. This company opened a railway from Winslow to East Vassalboro on June 27, 1908, and continued it from East Vassalboro to Augusta by November 1908.

The Lewiston and Waterville lines were connected by an arched concrete bridge across the Kennebec between Winslow and Waterville that opened Dec. 15, 1909, Cummings found. He wrote that after the 1936 flood took out the highway bridge, the trolley bridge was temporarily the only local way to cross the Kennebec (except by the footbridge).

The trolley bridge had survived its builders. The Lewiston, Augusta & Waterville became the Androscoggin & Kennebec in 1919 and stopped running July 31, 1932.

Cummings described in some detail routes, equipment, power sources and facilities. Fairfield’s two carhouses were on High Street (plus a smaller one on Main Street for the Fairfield & Shawmut); Benton had one, at Benton Falls; Waterville had one, at the Waterville Fairgrounds; and Oakland had elegant Messalonskee Hall, on Summer Street at the foot of Church Street near the lake. Cummings wrote that the Hall’s ground level accommodated three trolley tracks; the basement had a restaurant and a boathouse; and on the second floor were a dance hall and dining room.

The trolley fare remained a nickel until 1918, rose to seven cents that year and later to 10 cents, Cummings wrote; but regular riders could buy tickets in bulk and get a discount. Children rode for half price.

Schedules called for a trolley-car every half hour on each of the various routes. Cummings commented that as more and more automobiles and trucks competed for space on the streets, staying on schedule became increasingly challenging.

The Waterville, Fairfield & Oakland surrendered on Oct. 10, 1937. On its final day, passengers again filled the cars, as when the first electric cars ran more than 45 years earlier. Cummings wrote that the last trip over the Waterville to Oakland line began at 10:35 p.m. on Oct. 10; the last run to Fairfield began at 12:40 a.m. on Oct. 11. Bus service began at 5:15 that same morning.

Main sources

Cummings, O. R. , Toonervilles of Maine The Pine Tree State (1955)

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Websites, miscellaneous.