SCORES & OUTDOORS: Take precautions against browntail moth hairs when working outdoors

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

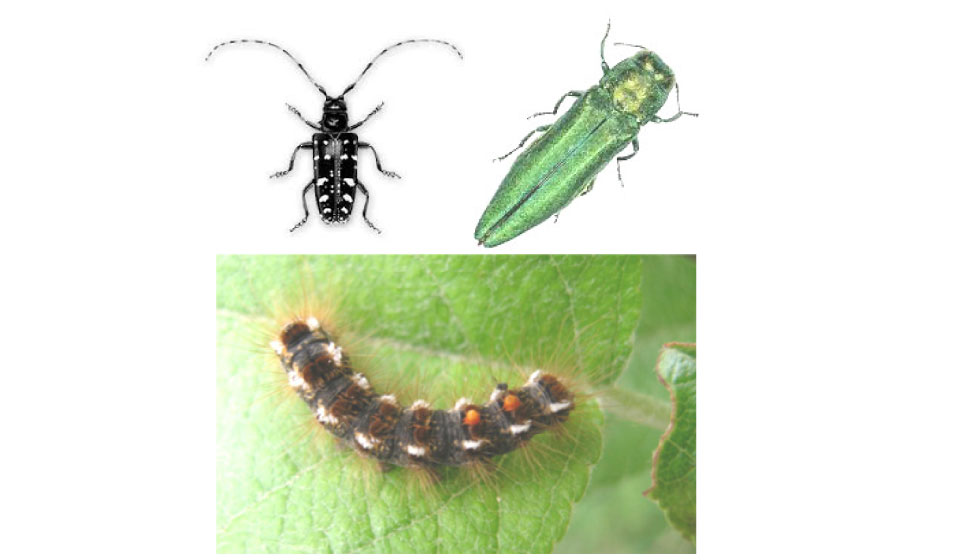

Last weekend while closing camp for the season, I had an encounter with the hickory tussock caterpillar. Although I didn’t touch it, but merely flicked it off a cleaning bottle, I think I stirred up its hairs and came down with a mild rash on my forearm. It lasted a little over a day.

Later in the week, I heard complaints from other people who have mysteriously developed a rash on their forearms or legs. That led me to thinking they had probably come in contact with the hickory tussock or, even more possible, the browntail moth caterpillar.

A couple of days ago, I received a press release from the Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Maine Forest Service, about the browntail moth caterpillar.

At this time, I will share that news release with you.

Maine Center for Disease Control and Prevention (Maine CDC), Maine Forest Service (MFS), and 211 Maine remind the public that browntail moth hairs remain in the environment and can get stirred up during fall yardwork. Tiny hairs shed by the caterpillars can cause a skin reaction similar to poison ivy. They can also cause trouble breathing and other respiratory problems.

The caterpillars are active from April to late June/early July.

“While browntail moth caterpillars might not be as noticeable at this time of the year, their hairs remain toxic and in the environment for one to three years,” said Maine CDC Director Nirav D. Shah. “It is important that Mainers take the proper prevention measures when working outside this fall.”

The hairs can lose toxicity over time. Hairs blow around in the air and fall onto leaves and brush. Mowing, raking, sweeping, and other activities can cause the hairs to become airborne and result in skin and breathing problems.

To protect yourself from browntail moth hairs while working outdoors:

- Wear a long-sleeve shirt, long pants, goggles, a dust mask/respirator, a hat and disposable coveralls.

- Rake or mow when the ground is wet to prevent hairs from becoming airborne.

- Cover your face and tightly secure clothing around the neck, wrists, and ankles.

- Do not rake, mow the lawn, or use leaf blowers on dry days.

- Use pre-contact poison ivy wipes to help reduce hairs sticking into exposed skin.

- Take extra care when working under decks or in other areas that are sheltered from rain.

- Take cool showers and change clothes after outdoor activities to wash off any loose hairs.

- Use caution with firewood stored in areas with browntail moths, especially when bringing it indoors.

Most people affected by the hairs develop a localized rash that lasts for a few hours up to several days. In more sensitive people, the rash can be severe and last for weeks. Hairs can also cause trouble breathing, and respiratory distress from inhaling the hairs can be serious. The rash and difficulty breathing result from both a chemical reaction to a toxin in the hairs and a physical irritation as the barbed hairs become stuck in the skin and airways.

Most people affected by the hairs develop a localized rash that lasts for a few hours up to several days. In more sensitive people, the rash can be severe and last for weeks. Hairs can also cause trouble breathing, and respiratory distress from inhaling the hairs can be serious. The rash and difficulty breathing result from both a chemical reaction to a toxin in the hairs and a physical irritation as the barbed hairs become stuck in the skin and airways.

There is no specific treatment for the rash or breathing problems caused by browntail moth hairs. Treatment is focused on relieving symptoms.

For more information:

- Contact 211 Maine for answers to frequently asked questions on browntail moths, such as browntail moth biology, management, pesticide options, health concerns, and reducing toxic hair exposure:

- Dial 211(or 1-866-811-5695)

- Text your ZIP code to 898-211

- Email info@211maine.org

- To see Maine CDC’s browntail moth frequently asked questions page, visit: https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-borne/browntail-moth/browntail-moth-faq.shtml

- To see Maine Forest Service’s browntail moth exposure risk map, visit: https://www.maine.gov/dacf/mfs/forest_health/documents/browntail_moth_risk_map.pdf.

I know that some of the suggestions of what to wear when doing yard work, or when to do it, doesn’t quite fit into your routine or schedule, but there is the old saying, “an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Who was the last Boston Red Sox left handed pitcher to win 20 games in a season?