Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Granges – Part 7

by Mary Grow

Hinckley Grange

Last week’s article was on the two Fairfield Grange organizations, still-active Victor Grange, in Fairfield Center, and no-longer-active Hinckley Grange, with its Hall across the Kennebec River from Fairfield, in Clinton. There is one more connection between the Grange and the town of Fairfield, a connection that brings us back to the National Register of Historic Places.

Maine State Grange voted at its 22nd meeting, held in Bangor in 1895, to raise money to build and equip a “cottage” for the new “Girls’ Farm” at what was then Good Will Homes, in Hinckley, one of Fairfield’s original seven villages.

Good Will Homes, for a while Goodwill Home-School-Farm and now Goodwill-Hinckley, is a charitable organization dedicated to helping orphaned and at-risk children and young adults. Its multi-building campus stretches along about two miles of Route 201 between Nye’s Corner to the south and Pishon’s or Pishons Ferry to the north.

Connecticut native George Walter Hinckley (1853-1950) founded the institution in 1889 as a home for boys, with the girls’ division added not long afterward. By the time Hinckley died, Wikipedia says, the school owned 3,000 acres, had 45 buildings and was serving thousands of young people.

The original Grange Cottage was dedicated on Dec. 20, 1897, according to an on-line source. The building burned in 1912 and was promptly replaced. On-line photos on the mainememory site, from the L. C. Bates Museum collection, include a 1908 photo of the first cottage and a 1912 photo of the second cottage.

Both buildings were two full stories high with third-floor windows in front and side gables. Each had an open front porch and appeared to have a basement, though in the 1912 photo the foundation is hidden by the snow around the building.

The 1912 building was designed by Augusta architect, Charles Fletcher. It was larger than the first one, and the larger third-floor windows imply more usable space in the gables. The front porch wrapped around part of one side.

(Charles Fletcher also designed the 1890 Doughty Block, at 265 Water Street, in Augusta. See the Feb. 10 issue of The Town Line.)

The second Grange Cottage burned in 1987 and was replaced by a third building.

According to the 2009 Journal of Proceedings of the One Hundred Thirty Sixth Annual Convention of the Maine State Grange, Goodwill-Hinckley had just discontinued its residential program and the use of Grange Cottage. The state Grange’s Committee on Women’s Activities was holding money intended for the building, which Goodwill-Hinckley owned; the meeting report says the money would be “redirected if the program does not start up again.”

Grange Cottage is in the section of the Goodwill-Hinckley campus described in the application for National Register listing (completed in November 1986; the property was added Jan. 9, 1987). The area designated as historic includes 33 buildings (two are complexes of buildings), “the original historic core” of the Hinckley Home-School-Farm, on about 525 acres.

Martin Stream, a major tributary that drains northern Fairfield into the Kennebec, divides the historically significant area. The application says the main campus, including the first cottages for boys, is south of the stream; the area where the first girls’ cottages were built is north of it.

Historian Frank Beard, writing the application for the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, explained the significance of Goodwill-Hinckley in two ways. Socially, he wrote, it was “an early home,” perhaps the first in the United States, for “indigent and homeless children.” Architecturally, its buildings, constructed between 1889 and 1930, “represent an important concentration of period buildings.”

The description of Grange Cottage in the application is of the 1913 building, the one that burned soon after the campus was added to the National Register.

Another among the 33 buildings is on the National Register of Historic Places separately, the L. C. Bates Museum, listed Oct. 4, 1978 (see below).

The other buildings include three schools, (Charles E.) Moody (built in 1905-1906), Edwin Gould (built in 1926-27) and (George C.) Averill (built in 1930); Moody Memorial Chapel (built in 1897 and enlarged in 1927); Carnegie Library (built in 1906-1907); Prescott Memorial Administration Building (built in 1916 and substantially remodeled in 1921-22); Kent Woodworking Shop (built in 1919); and residential buildings.

The earliest residential building is Golden Rule Cottage, designed by architect Henry Dexter, of Dexter, and built in 1891. Beard described it as a two-and-a-half-story Queen Anne style wood-frame building with a “veranda” and a “rear porch with fan-shaped brackets.”

The newest residence on the list, Pike Cottage, dates from 1935 (and is the only building in the historic area constructed after 1930). Colonial Revival style, wooden, two and a half stories, it has a gable roof and an east-side veranda.

Beard called three cottages, Gifford House, Hinckley House and Price House, part of “teachers’ row.” They were all built in 1904, presumably as faculty housing.

Also in the historic area are Easler Cottage and a cluster of buildings identified as Easler Farm. The late-19th-century Easler Farm includes two wooden barns, a metal-sided animal barn and a garage.

Beard described Easler Cottage, built in 1900, as Queen Anne style, two-and-a-half stories, with a “pedimented veranda supported on turned posts with corner brackets and spindle work.” He listed with the cottage a story-and-a-half barn with a gable roof and a cupola.

The sole nameless building listed in the application is a story-and-a-half mid-19th-century wood frame “house.”

The L. C. Bates Museum is in the 1903 Quincey Building, designed by Lewiston architect William Robinson Miller (1866-1929). The brick building is an example of the elaborate Romanesque architecture in which he specialized.

The application for National Register listing mentions the building’s “hipped roof, dormers, recessed round-arched entry, [and] symmetrical round stairwell towers on principal (east) elevation.” A Wikipedia article adds its “distinctive terracotta egg and dart ornamentation, and arched windows.

Inside, the museum has 32 Maine dioramas painted by American Impressionist Charles Daniel Hubbard (1876-1951); impressive natural history collections, from mammals to minerals; and Native American baskets, archaeological artifacts and other Maine historical items.

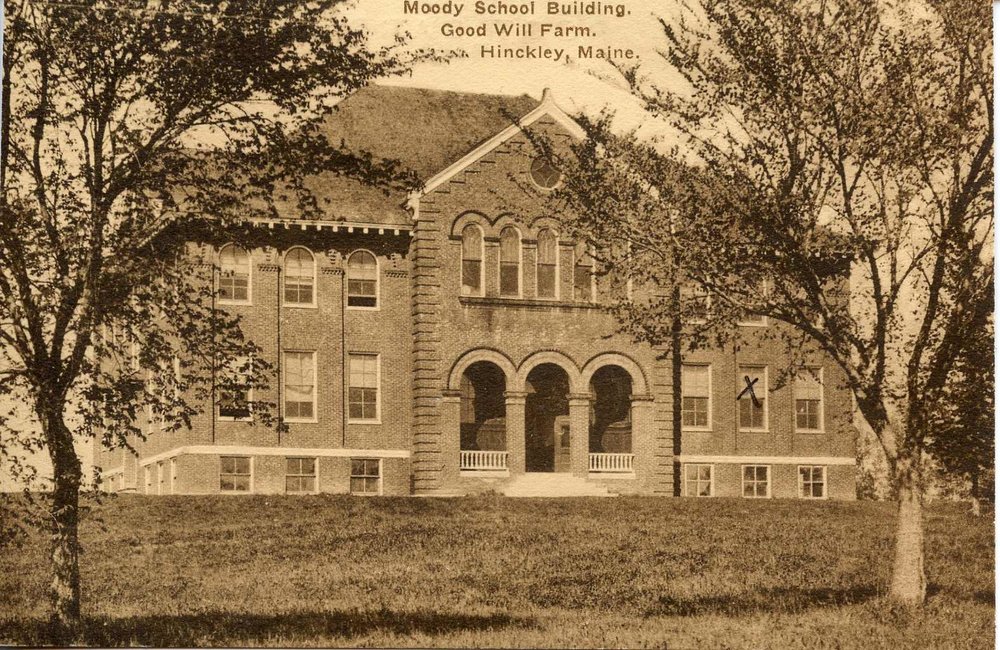

The Moody School, architect Miller’s earlier building on the campus, honors Charles Eckley Moody, of Bath. A Goodwill-Hinckley web page says Hinckley visited Moody’s two sisters, Mary and Frances, in 1894, a year after Moody died. The visit reminded them that their late brother had favored Hinckley’s project, so they donated $25,000 to build the school. Dedicated Jan. 1, 1896, it was the first brick building on campus.

(The Rev. Albert Teele Dunn, D. D., is quoted as calling the dedication “one of the proudest, happiest days” in Hinckley’s life. Dunn later was honored in Portland by naming Dunn Memorial Church after him, because he organized its congregation shortly before he died in 1904. The church later became Central Square Baptist Church and is now Deering Center Community Church.)

Beard described the two-story Moody School building as Renaissance style, “with hipped roof,…central pavilion with arcaded recessed entry, square-headed and round-arched windows.”

The Edwin Gould School was added in 1926-1927 with funds donated by railroad and Wall Street tycoon Edwin Gould (1866-1933), after he read of the need for a girls’ school on the Goodwill campus. According to on-line sources, the name honors his son, Edwin Gould, Jr., who died in 1917 in a hunting accident.

The building was designed by the Portland architectural firm of Miller, Mayo & Beal, whose members were William Miller, doing his third Goodwill-Hinckley project; Miller’s former head draftsman, Raymond J. Mayo; and Miller and Mayo’s former head draftsman, Lester I. Beal. The firm specialized in school buildings.

An on-line photo from the L. C. Bates Museum’s collection and historian Beard’s description of the Gould School depict a two-story brick Georgian Revival building with chimneys on each end. The building had two entries, one near each end, “sheltered by Doric porticos,” and a wooden cupola atop the middle.

On-line information about the Gould School says it closed in 2009 and stood vacant or was used for storage for four decades. In 2012, officials decided to reopen the building.

By then, there were holes in the roof “leading to severe water damage and rot.” The need for taller rooms on the ground floor required excavation and control of water under the building. Original masonry and interior and exterior trim were restored.

(Gould Academy, in Bethel, originally organized by local citizens as Bethel Academy, was renamed after Rev. Daniel Gould willed it $842 in 1843. Gould Academy’s website says annual tuition is currently $38,650 for commuting students and $62,700 for boarders. This information has nothing to do with Goodwill-Hinckley.)

Colonial Theater update

The restored decorative element, now completed, on top of the Augusta Colonial Theater. Caught at a moment by Dave Dostie – 2021. May.

In the May 14 Central Maine newspapers, the Kennebec Journal and The Morning Sentinel, reporter Keith Edwards continued his description of the reconstruction of the Colonial Theater in Augusta, specifically the elaborate decorations on the front (see The Town Line, Feb. 4).

The Water Street theater has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1914. Edwards wrote that the façade work is part of a restoration project started “several years ago,” after the building had been vacant since 1969. Organizers turned to Maine artisans who had the skills to replicate work originally done in the 1920s.

Total cost of the restoration is estimated at up to $8.5 million. Donations are welcome; they may be made via the website, augustacolonial.org, or by mail to Augusta Colonial Theater Offices, 70 State Street, Augusta, Maine 04330.

People wanting to read Edwards’ article in the Central Maine newspapers should look for the headline “Augusta’s Colonial Theater topped by work of artisans.”

Main sources

Websites, miscellaneous.

Next week: more Goodwill-Hinckley buildings.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!