Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Three notable citizens – Part 1 of 3

by Mary Grow

George J. Mitchell

This writer hopes you-all aren’t tired of reading about people, because four more biographical pieces are coming your way. After some of the obscure Maine governors you probably never heard of, these four will be people born in or otherwise connected to the central Kennebec area whose names should be familiar. All of them have written about themselves or been written about, or both, so if you’re interested, you should be able to find out more about them than space permits in these pages.

George John Mitchell is usually referred to as Senator Mitchell, but that’s only one title earned by this Waterville native. His 2015 memoir is The Negotiator, another appropriate title; and one could add lieutenant (in the Army), chairman (of a variety of committees and boards), judge (federal district court in Maine), chancellor (of the Queen’s University of Belfast in Northern Ireland) and (honorary) Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire.

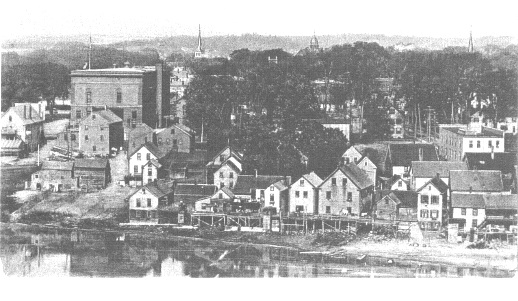

Mitchell was born Aug. 20, 1933, the youngest son of Lebanese immigrants George and Mary Mitchell, in the part of Waterville between the railroad tracks and the Kennebec River known as Head of Falls. His mother, like many other Lebanese (and French-Canadian) immigrants, worked in the textile mills that were important in Waterville’s economy; his father was a laborer for a utility company and later a janitor and groundskeeper at Colby College.

Mitchell’s three older brothers, Paul, Johnny (known as “Swisher” on the basketball court) and Robbie, were talented athletes with whom George tried to compete, with limited success. The youngest of the family is their sister Barbara, now Barbara Atkins, still a Waterville resident.

The whole family was hard-working. Mitchell remembers two jobs particularly: delivering newspapers when he was so young that a full bag was hard to lift, and picking green beans on local farms. Later, he worked his way through college, and later still held a full-time job while earning his law degree at night.

Mitchell’s father wanted all five children to be college graduates, and all of them were. Mitchell writes that because of his father’s encouragement, he started high school the September after his 13th birthday and graduated at 16.

With the help of a Bowdoin graduate from the utility company where Mitchell’s father had worked, Mitchell entered Bowdoin, graduating in 1954. In addition to working year-round, he played sports, joined a fraternity and joined the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

When the Army called him in December 1954, he attended its Intelligence School, in Baltimore, and in 1955 was made a second lieutenant and sent to Berlin, Germany. He and another newcomer went together to the office where assignments were handed out. Mitchell opened the office door and politely let the other man go in first. The officer assigned the first man to supply, the second to security, before he even asked who was who.

As a result of that act of courtesy at the door, Mitchell had an interesting 18 months’ service in Berlin, during which he worked with a graduate of Georgetown University’s law school in Washington. As Mitchell debated whether to stay in the army – he was a first lieutenant by then – or apply to graduate school in European history, his Bowdoin major, or go to law school, his friend urged him to go to law school, specifically Georgetown. Another fellow soldier with similar plans proposed they share an apartment.

Mitchell therefore entered law school at Georgetown in January 1957. Through that decision, he not only earned a law degree in 1961, but met his first wife, Sally, who lived near him while working in Washington. The two married in August 1959, had a daughter, Andrea, born in May 1965, and divorced amicably in March 1987, partly because Sally did not share her husband’s interest in politics.

That interest began in January 1962, when Mitchell was invited to join Maine Senator Edmund Muskie’s staff. He worked for Muskie, whom he admired and respected, in Washington until early 1965 when that commitment ended and he achieved a long-held wish to move back to Maine, joining a Portland law firm.

In Maine, from 1966 on, Mitchell chaired the state Democratic Party for two years and served on the national Democratic committee for eight years; ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1974, losing to Independent James Longley; served as United States Attorney in Maine from 1977 to 1979; and became a federal district judge in October 1979, presiding in Bangor.

The two federal appointments were the result of nominations by Muskie, then a United States Senator. Six months after Mitchell became a judge, at the end of April 1980, President Jimmy Carter chose Muskie as his new Secretary of State, creating a vacant Senate seat. Governor Joseph Brennan, elected in 1978 as Longley’s successor, appointed Mitchell to succeed Muskie in May 1980.

Mitchell finished Muskie’s term and won election in his own right in 1982 and again in 1988. In 1988 his fellow Democrats elected him majority leader. His memoir describes a Senate that worked hard to reconcile competing interests, with men (he mentions no women who played leading roles in the 1980s) who tried to serve their constituents’ interests within the national interest and who were often personal friends across political divisions.

Mitchell could have added “Justice” to his titles, but he rejected the opportunity. Early in March 1994 he had announced he would not seek another Senate term that fall; in April, Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackman announced his impending retirement. President Bill Clinton wanted to nominate Mitchell as his successor.

Mitchell wrote in his memoir that at that point, he thought it more important to stay as Senate majority leader to continue working on a health care bill the administration was sponsoring. He therefore declined the court appointment. (The health care bill did not pass; the President chose Stephen Breyer for the court seat.)

Mitchell gives multiple reasons for leaving the Senate after a bit more than two terms, the second as majority leader. He thought he was still popular with Maine voters and did not want to outstay his welcome. He found the job all-consuming and wanted more time for himself, especially since he and his second wife, Heather, planned to marry in December 1994. His dislike for the fund-raising that he learned was full-time, not just in election years, had not decreased, although by December 1993 he had achieved his $2 million fund-raising goal for a re-election campaign.

(Things have changed since 1993. According to recent press reports, as of June 30, 2020, Senator Susan Collins had raised $16.7 million for this year’s re-election campaign and spent a little over 12 million, though she had no challenger in the July 14 primary election. Sara Gideon, who won a three-way primary to become Collins’ opponent in November, raised almost $24.2 million and spent almost $18.8 million.)

Declining the Supreme Court nomination led to what many commentators consider the high point of Mitchell’s career, his role in the peace negotiations in Northern Ireland that culminated in the Easter Sunday agreement, signed April 10, 1998. The agreement ended centuries of violence, most recently 30 years of bloody warfare between Unionists or Loyalists, the mostly Protestant group that wanted Northern Ireland to stay in the United Kingdom with Britain, and Nationalists or Republicans, who wanted to unite with the Republic of Ireland.

A Britannica article on line estimates that between 1968 and 1998 the fighting killed 3,600 people and injured an additional 30,000 or more, including local fighters, innocent residents and British peacekeepers. By 1997, most of the parties on both sides had joined peace talks that Mitchell mediated. The 1998 settlement dealt with political power-sharing and continued cooperation, and although there have been bloody incidents and delays in implementation, on balance Mitchell’s work has held.

In appreciation of his mediation, Mitchell received an honorary degree from Queen’s University in July 1997, before he was invited to become chancellor. On March 17, 1999, President Clinton awarded him a Presidential Medal of Freedom; and on July 15 that year, Queen Elizabeth bestowed his honorary knighthood.

At the beginning of President Barack Obama’s first term in January 2009, Secretary of State, Hillary Rodham Clinton, asked Mitchell if he would become the president’s special envoy for Middle East peace. Though well aware the failure of previous efforts, Mitchell agreed to a two-year appointment. His memoir indicates that he talked often with leaders on both sides and within both sides (for neither the Israelis nor the Palestinians were totally united on policy), but made no significant progress.

Mitchell’s main post-Senate position was with a large Washington-based international law firm, where he was still when he wrote his 2015 memoir. He took leave in 2009 to serve as the Middle East negotiator, and has found time for numerous other activities. They include serving as chairman of the board of the Walt Disney Company; being a member of an investigating committee that looked into allegations of bribery in selecting cities to host international Olympic competitions; and twice assisting in investigating major-league baseball’s problems with performance-enhancing drugs (without, he writes, diminishing his love for the sport).

In addition to The Negotiator, Mitchell has written books about the environment and his work in Northern Ireland and the Middle East. He and former Republican Senator William Cohen co-wrote a book on the Iran-Contra hearings, published in 1988.

The legacy he talks about with pride toward the end of his memoir is the Mitchell Scholarship Fund, intended to help Maine high-school graduates go to college. Mitchell started it when he left the Senate: he asked donors to his $2 million re-election fund whether they wanted their money back or wanted it used to send Maine students to college.

The $1 million donors left with him, plus personal fund-raising, grants and other contributions, created the scholarship fund. As he finished his memoir, it had given more than $11 million to almost 2,300 students. In 2015 the award was $7,500; Mitchell wrote that he hoped it would soon be $10,000, and it now is, according to Mitchell Scholarship information on the Finance Authority of Maine website.

Main sources

Mitchell, George J., The Negotiator, 2015

Websites, miscellaneous

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!