SCORES & OUTDOORS: What are crazy worms and where did they come from?

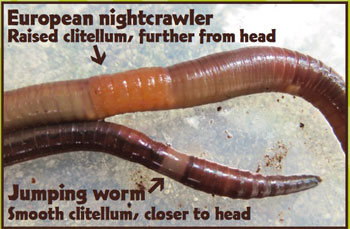

The common earthworm, top, and the crazy worm, below. Note the difference in the clitellum (a raised band encircling the body of worms, made up of reproductive segments), and its location on the two species. (photo courtesy of Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources)

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

Did you know there are no native earthworms in Maine? Here in the Northeast where glaciers scrubbed our bedrock bare a few years back we have no native earthworms. Non-native earthworms from Europe (such as nightcrawlers) have become well established here through early colonial trading. Though they are beneficial to our gardens, earthworms can have destructive effects on our forests.

Are you tired of hearing about new invasive species. Yeah – right there with you. Aside from the fact that there’s too much bad news around as it is, we’re still working on a solution for those good old-fashioned pests that rival the common cold in terms of eluding conquest. Japanese beetles, European chafers, buckthorn, wild parsnip, Japanese knotweed – enough already.

And now, there is another species of worms out there that are not so welcome.

Crazy worms are a type of earthworm native to East Asia. (Here we go with Asian invaders, again. It seems every invasive species, of any kind, originates in Asia). They are smaller than nightcrawlers, reproduce rapidly, are much more active, and have a more voracious appetite. This rapid life cycle and ability to reproduce asexually gives them a competitive edge over native organisms, and even over nightcrawlers. They mature twice as fast as European earthworms, completing two generations per season instead of just one. And their population density gets higher than other worms. And they can get to be eight inches in length, longer than a nightcrawler. When disturbed, crazy worms jump and thrash about, behaving like a threatened snake.

Crazy worms are known and sold for bait and composting under a variety of names including snake worms, Alabama jumper, jumping worms, Asian crazy worm. They are in the genus Amynthas, and distinguishing between the several species in the genus can be difficult. All species in this genus are considered invasive in Maine. It is illegal to import them into Maine (or to propagate or possess them) without a wildlife importation permit from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MDIFW). For more information, visit MDIFW’s Fish & Wildlife in Captivity webpage.

Crazy worms are native to Korea and Japan, and are now found in the United States from Maine to South Carolina and west to Wisconsin. Crazy worms were first collected from a Maine greenhouse in 1899, though an established population of this active and damaging pest was not discovered here until about 2014 when two populations were discovered in Augusta (one at the Viles Arboretum) and two populations were found in Portland. They have also been found in a rhododendron display at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, in Boothbay. It is believed that crazy worms are not yet widespread in Maine, but they have been discovered in some new locations since 2014, including nursery settings. If allowed to spread, crazy worms could cause serious damage to horticultural crops and the forest ecosystem in Maine.

So, why are crazy worms a problem? Crazy worms change the soil by accelerating the decomposition of leaf litter on the forest floor. They turn good soil into grainy, dry worm castings (a/k/a poop) that cannot support the native understory plants of our forests. Other native plants, fungi, invertebrates, and vertebrates may decline because the forest and its soils can no longer support them. As native species decline, invasive plants may take their place and further exacerbate the loss of species diversity.

In nurseries and greenhouses, crazy worms reduce the functionality of soils and planting media and cause severe drought symptoms. After irrigating or rains, you may find these worms under pots. These worms may be inadvertently moved to new areas with nursery stock, or in soil, mulch, or compost.

Many of Maine’s forests are already under pressure from invasive insect pests, invasive plants, pathogens, and diseases. Crazy worms could cause long-term effects on our forests.

When handled, these worms act crazy, jump and thrash about, behaving more like a threatened snake than a nightcrawler. They may even shed their tail when handled. Annual species, tiny cocoons overwinter in the soil, and the best time to find them is late June to mid-October. In nurseries, they can often be found underneath pots that are sitting on the ground or on landscape fabric. In forests, they tend to be near the surface, just under accumulations of slash or duff.

There are precautions you can take.

Do not buy or use crazy worms for composting, vermicomposting, gardening, or bait. Do not discard live worms in the wild, but rather dispose of them (preferably dead) in the trash. Check your plantings – know what you are purchasing and look at the soil. Buy bare root stock when possible. Be careful when sharing or moving plantings, cocoons may be in the soil.

What ever happened to just having regular nightcrawlers or “trout worms”?

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

In 2008, which Boston Red Sox rookie stole 50 bases?

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!