Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Early land titles

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

The lawyers discussed in this series earlier this spring were undoubtedly important in the lives of European settlers in the central Kennebec Valley. Before the lawyers, and equally if not more important, were another group of professional men: the surveyors.

Several surveyors’ names appear in 18th-century records, usually because the men were hired by the Plymouth Company/Kennebec Proprietors, the Boston-based companies with deeds to large parts of the area. Those most often mentioned include, in birth order, Ephraim Ballard (May 6 or May 17, 1725 – Jan. 7, 1821), John McKechnie (about 1730/1732 -– 1782), John Jones (c. 1743 – Aug. 16, 1823) and Nathan Winslow (April 1, 1743 — ? [after January 1807]).

Ballard is named as the surveyor of part of Albion, an area Henry Kingsbury, in his 1892 Kennebec County history, said the proprietors had given to Nathan Winslow; and part of Palermo. He was the husband of Martha Ballard, whose diary was made famous by Laurel Thacher Ulrich’s 1990 book titled A Midwife’s Tale.

McKechnie also surveyed part of Albion, in 1769; and the Town of Winslow.

Jones surveyed the west side of Sidney, beyond Winslow’s riverfront lots, in 1774; the area east of Vassalboro, including what became China, in the fall of 1773 and spring of 1774, with Abraham Burrell or Burrill (who became one of the first settlers around China Lake).

Nathan Winslow laid out lots in Vassalboro, including the part on the west side of the river that became Sidney, in 1761.

Among other surveyors mentioned less often in histories of the settlement of the central Kennebec valley are Paul Chadwick, General Joseph Chandler, Isaac Davis, Charles Hayden, John Howe, Josiah Jones, Bradstreet Wiggin or Wiggins and Dr. Obadiah Williams.

* * * * * *

Alice Hammond included in her history of Sidney a summary history of land titles in the area that became Maine, and more specifically in the valley of the Kennebec River. A summary of her summary might help readers sort out who owned what when.

The Augusta lawyer named Wendall Titcomb who wrote the chapter on Sources of Land Titles for Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history said that “…the Crown of England is the source to which trace all lines of title to lands within the county of Kennebec.” Hammond agreed.

She started with King James I’s 1606 grant giving the London Company the southern part and the Plymouth Company the northern part of North America between latitude 34 degrees and latitude 45 degrees.

The 45-degree line runs east-west through Maine north of present-day Skowhegan and Bangor. The 34-degree line runs through the southern United States, including Georgia, South Carolina and extreme southeastern North Carolina.

While the London Company settled Jamestown, Virginia, Plymouth Company representatives began trading with Natives and establishing fishing ports, but made no permanent settlements.

In 1620, Hammond wrote, a British stock company named the Council for New England, “successor to the Plymouth Company,” got a grant covering the territory between 40 and 48 degrees. Titcomb gave the full title: “The Council Established at Plymouth in the County of Devon for the planting, ruling and governing New England in America.” This company sponsored the 1620 Pilgrim settlement at Plymouth, Massachusetts.

One of the colonists, William Bradford, served as the colony’s governor for part of the time. He petitioned the Council for more land to support the colony’s growing population, and on Jan. 13, 1629, got the Kennebec or Plymouth Patent.

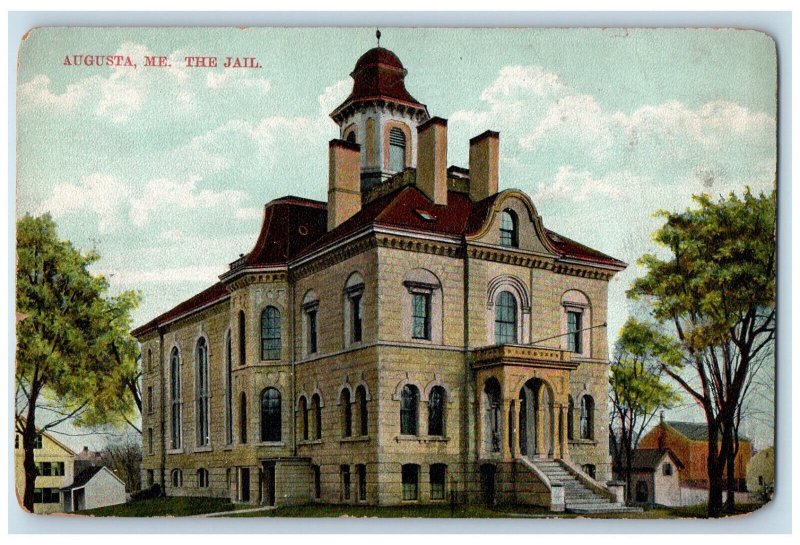

This grant covered 15 miles on both sides of the Kennebec River from the coast inland beyond present-day Skowhegan, about 1.5 million acres. It included the right to establish three trading stations, the one farthest upriver at Cushnoc (later Augusta).

Profits from the Kennebec trade declined over the years. On Oct. 17, 1661, Titcomb said, Boston businessmen Antipas Boyes (Boyce, Boies), Thomas Brattle, Edward Tyng and John Winslow bought the land along the Kennebec, for 400 pounds. These men organized themselves as the Kennebec Proprietors.

(Kingsbury added a footnote: the deed for the 1661 transaction was executed on Oct. 15, 1665, and “recorded in the York County registry in 1719.”)

Mostly because of wars with the Natives and their French allies who helped them from farther north, the so-called French and Indian Wars (1688 to 1763), the Proprietors did not develop their holdings. Over almost a century, their shares in the organization were divided among heirs, some ending up with 1/192 of a share, Hammond wrote.

The first of four separate French and Indian wars historians call King William’s War; it began in 1688 and was formally ended by the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick. The second war, known as Queen Anne’s War, or Dummer’s War, started in 1702 and ended with the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht.

James North, in his history of Augusta, wrote that the group he called the Pejepscot Proprietors took advantage of the post-1713 peaceful interlude to hire Joseph Heath to survey 111 miles of the Kennebec, as far inland as Norridgewock. Heath’s plan is dated May 16, 1719, North said.

(Joseph Heath, sometimes called Captain or Colonel, worked as a surveyor in several parts of Maine early in the 1700s, before the British settlements in the central Kennebec Valley. On-line documents refer to his plans for part of Brunswick [1717]; the Plymouth Patent [1719]; and a 1719 map and description of Norridgewock. North said Heath was “probably” the first commander at Fort Richmond, built in 1719 on the Kennebec below Gardiner.)

In August 1749, after the third of the four wars (King George’s War, or the War of Jenkins’ Ear) had ended with the October 1748 Treaty of Aix la Chapelle, some of the hereditary proprietors met and re-organized themselves as, Hammond wrote, “The Proprietors of the Kennebec Purchase from the late colony of New Plymouth,” aka either the Kennebec(k) Company/Proprietors or the Plymouth Company.

(This organization is the subject of a scholarly 1975 book by Gordon E. Kershaw titled The Kennebeck Proprietors 1749-1775. Kershaw focused on the group’s financial and legal interactions with the British government, in Massachusetts and in London.)

These men thought permanent settlements on the Kennebec River would be the way to profit from their holdings. North wrote that an early step was to get an exact understanding of what they owned. They hired their first surveyor pursuant to a December 1749, vote; and a surveyor named John North (later identified as Capt. John North) in October 1750.

North was again hired in 1751, and in that year and the next made a plan of the river and its tributaries and laid out at least some lots to be sold, from the ocean to Cushnoc (that is, inland as far as southern Augusta).

North mentioned repeatedly that the native inhabitants of the Kennebec Valley, egged on by the French from the north, tried to deter the expanding British settlements. The Proprietors and the Massachusetts authorities cooperated to build two forts on the east bank of the river in 1754.

Fort Halifax, built by British troops under General John Winslow (see box) was at the mouth of the Sebasticook, near the native village called Ticonic. Fort Western at Cushnoc served as a supply depot for and link to the upriver fort.

The fourth and final of the French and Indian Wars (the French and Indian War [singular], or the Seven Years’ War) broke out in 1754. Fighting in North America was over by 1760, although the formal peace treaty between Great Britain and France was not signed until Feb. 10, 1763 (Treaty of Paris).

With the Kennebec valley at peace, more people were willing to move there, and skilled surveyors able to establish precise lot lines became even more important.

A man named Winslow who was not a surveyor

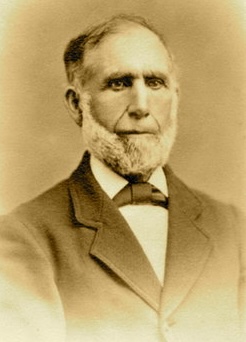

The Town of Winslow was named after British General John Winslow (May 10, 1703 – April 17, 1774), not surveyor Nathan Winslow. Your writer found no evidence the two were related.

General Winslow, according to Barry M. Moody’s article in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography (found on line), was a member of a prominent New England family, descendant of two former governors of the Plymouth Colony (Edward and Josiah Winslow).

Winslow was born May 10, 1703, in Marshfield, Massachusetts. In February, 1725, he married Mary Little, born in Marshfield in September 1704 (according to Wikipedia). They had three sons, Josiah, Pelham and Isaac. (Moody said only two sons; and added that Winslow took a second wife, Bethiah [Barker] Johnson [no date] – possible, since, according to Wikipedia, Mary died in 1772.)

Winslow’s first military experience was on an unsuccessful 1740 British expedition to Cuba, as a captain in a provincial militia company. He then joined the regular British army, serving in eastern Canada.

Moody said he briefly abandoned the army and returned to Massachusetts, where he represented Marshfield in the state legislature in 1752-53.

In 1754, Massachusetts Governor William Shirley made Winslow a major-general in charge of the 800-man force sent to the Kennebec to combat French and Native opposition to British settlements. There he oversaw construction of Fort Halifax.

Rev. Edwin Whittemore, in his 1902 Waterville centennial history, said Winslow left 300 men to build the fort and led the other 500 upriver as far as Norridgewock. In late summer, after the fort’s stockade and first buildings were finished, Whittemore wrote that Governor Shirley came north to inspect it “and highly commended Gen. Winslow and his men.”

(In a later chapter in Whittemore’s history, Aaron Appleton Plaisted commented on the varied spellings of “Ticonic.” Among them he listed Governor Shirley’s “Taconett” and General Winslow’s “Ticonnett.”)

The 1754 project in the Kennebec Valley “added greatly to his [Winslow’s] popularity, and he was thus a natural choice as the lieutenant-colonel of a provincial regiment raised by Shirley in 1755 to aid Lieutenant Governor Charles Lawrence of Nova Scotia in his attempts to sweep French influence from the province,” Moody wrote.

Winslow spent the spring and summer of 1755 in New Brunswick, Canada, where reducing French influence included heading the expulsion of the French Acadian settlers. Moody quoted from Winslow’s diary that the work did not please him; but “he carried out his orders with care, military precision, and as much compassion as circumstances allowed.”

Winslow returned to Massachusetts in November 1755. The next year, he “reached the high point of his military career” when Governor Shirley sent him to upstate New York to fight the French there.

On both expeditions, Winslow quarreled with his superior officers. Moody suggested both sides were to blame.

Back in Massachusetts by 1757, Winslow left the army. He again represented Marshfield in the Massachusetts legislature in 1757-58 and from 1761 to 1765.

Around 1766 Winslow moved about 15 miles to Hingham, Massachusetts. He died there in 1774.

Main sources

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.