The views of the author in the following column are not necessarily those of The Town Line newspaper, its staff and board of directors.

On the ballot this November is a question that has the potential to revolutionize internet access for residents of China. The question is also long, at over 200 words, a bit confusing and filled with legalese. As a resident of China, a technophile, and a reporter for The Town Line newspaper, I wanted to understand this initiative, figure out exactly what it’s attempting to accomplish, and try to find out what residents of China think about the future of local internet access.

In order to understand the issue, I attended two of the recent information sessions held by the China Broadband Committee and also sat down with Tod Detre, a member of the committee, who I peppered with questions to clear up any confusions I had.

I also created a post in the Friends of China Facebook group, which has a membership of more than 4,000 people from the town of China and neighboring communities, asking for comments and concerns from residents about the effort. Along with soliciting comments, I included in my post a survey question asking whether residents support the creation of a fiber optic infrastructure for internet access in China. (I should be clear here and point out that the question on the November ballot does not ask whether we should build a fiber optic network in China, only whether the selectboard should move forward with applying for financing to fund the initiative if they find there is sufficient interest to make the project viable. But for my purposes, I wanted to understand people’s thoughts on the goals of the effort and how they felt about their current internet access.)

My Facebook post garnered 86 comments and 141 votes on the survey question. One hundred and twenty people voted in favor of building a fiber optic network in China and 21 people opposed it. (This, of course, was not a scientifically rigorous survey, and the results are obviously skewed toward those who already have some kind of internet access and regularly utilize online platforms like Facebook.)

Before we get into the reasons why people are for or against the idea, let’s first take a look at what exactly the question on the ballot is and some background on what has led up to this moment.

The question before voters in November does not authorize the creation of a fiber optic network in China. It only authorizes the selectboard to begin the process of pursuing the financing that would be required to accomplish that goal – but only if certain conditions are met. So, what are those conditions? The most important condition is one of participation. Since the Broadband Committee’s goal is to pay for the fiber optic network solely through subscriber fees – without raising local taxes – the number of people who sign up for the new service will be the primary determining factor on whether the project moves forward.

If the question is approved by voters, the town will proceed with applying for financing for the initiative, which is projected to have a total estimated cost of about $6.5 million, paid for by a bond in the amount of $5.6 million, with the remainder covered through a combination of “grants, donations and other sources.” As the financing piece of the project proceeds, Axiom, the company the town plans to partner with to provide the internet service, will begin taking pre-registrations for the program. Although the length of this pre-registration period has not been completely nailed down, it would likely last anywhere from six months to a year while the town applies for financing. During this period, residents would have an opportunity to reserve a spot and indicate their interest in the new service with a refundable deposit of $100, which would then be applied toward their first few months’ of service once the program goes live. Because the plan for the initiative is for it to be paid for by subscriber fees rather than any new taxes, it is essential that the project demonstrates sufficient interest from residents before any work is done or financing acquired.

With approximately 2,300 structures, or households, that could potentially be connected to the service in China, the Broadband Committee estimates that at least 834 participants – or about 36 percent – would need to enroll in the program for it to pay for itself. Any number above this would create surplus revenue for the town, which could be used to pay off the bond sooner, lower taxes, reduce subscriber fees or for other purposes designated by the selectboard. If this number is not reached during the pre-registration period, the project would not proceed.

One of the problems this initiative is meant to alleviate is the cost of installing internet for residents who may not have sufficient internet access currently because bringing high speed cable to their house is cost prohibitive. The Broadband Committee, based on surveys they have conducted over the last several years, estimates that about 70 percent of residents currently have cable internet. The remaining 30 percent have lower speed DSL service or no service at all.

For this reason, for those who place a deposit during the initial signup period, there would be no installation cost to the resident, no matter where they live, including those who have found such installation too expensive in the past. (The lone exception to this guarantee would be residents who do not have local utility poles providing service to their homes. In those rare instances, the fiber optic cable would need to be buried underground and may incur an additional expense.) After the initial pre-registration period ends, this promise of free installation would no longer be guaranteed, although Axiom and the Broadband Committee have talked about holding rolling enrollment periods in the future which could help reduce the installation costs for new enrollees after the initial pre-registration period is over.

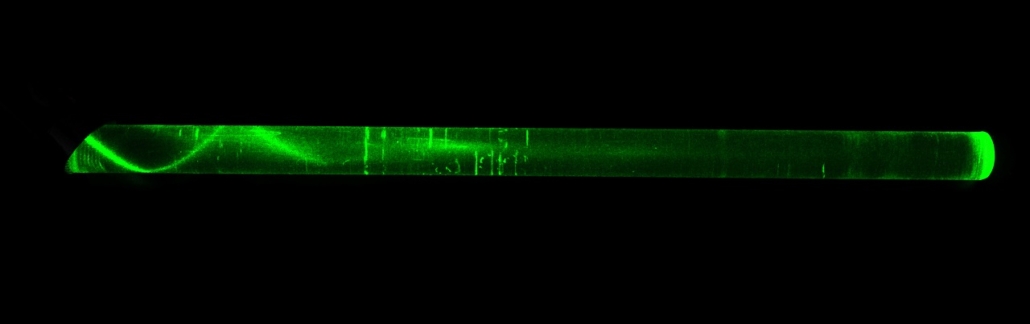

What are the benefits of the proposed fiber optic infrastructure over the cable broadband or DSL service that most residents have currently? Speed and reliability are the most obvious benefits. Unlike the copper cable used currently for cable internet, which transmits data via electrical pulses, fiber optic cable transmits data using pulses of light through fine glass fibers and does not run into the same limitations as its copper counterpart. The speed at which data can be transmitted via fiber optic cable is primarily limited by the hardware at either end of the connection rather than the cable itself. Currently, internet service travels out from the servers of your internet provider as a digital signal via fiber optic cable, but then is converted to an analogue signal as it is passed on to legacy parts of the network that do not have fiber optics installed. This process of conversion slows down the signal by the time it arrives at your house. As service providers expand their fiber optic networks and replace more of the legacy copper wire with fiber optics, the speed we experience as consumers will increase, but it is still limited by the slowest point along the network.

The proposed fiber optic network would eliminate this bottleneck by installing fiber optic cable from each house in China back to an originating server with no conversion necessary in between.

Both copper and fiber optic cable suffer from something called “attenuation,” which is a degradation of the strength of the signal as it travels further from its source. The copper cables we currently use have a maximum length of 100 meters before they must be fed through a power source to amplify their signal. In contrast, fiber optic cables can run for up to 24 miles before any significant weakening of the signal starts to become a problem. Moving from copper cable to fiber optics would virtually eliminate problems from signal degradation.

Another downside to the present infrastructure is that each of those signal conversion or amplification boxes require power to do their job. This means that when the power goes out, it shuts off the internet because these boxes along the route will no longer function to push the signal along. The infrastructure proposed by the China Broadband Committee would solve this problem by installing fiber optics along the entire signal route leading back to a central hub station, which would be located in the town of China and powered by a propane generator that will automatically kick on when the power goes out. With the proposed system, as long as you have a generator at your house, your internet should continue to work – even during a localized power outage.

There’s an additional benefit to the proposed fiber optic network that residents would notice immediately. The current cable internet that most of us use is a shared service. When more people are using the service, everyone’s speed decreases. Most of us know that the internet is slower at 5 o’clock in the afternoon than it is at 3 in the morning. The proposed fiber optic network is different however. Inside the fiber optic cable are hundreds of individual glass strands that lead back to the network source. A separate internet signal can ride on each of these strands without interfering with the others. Hawkeye Connections, the proposed contractor for the physical infrastructure part of the project, would install cable with enough individual strands so that every house along its path could be connected via a different strand within the cable. This means that no one would be sharing a signal with anyone else and internet slowdown and speed fluctuations during peak usage should become a thing of the past.

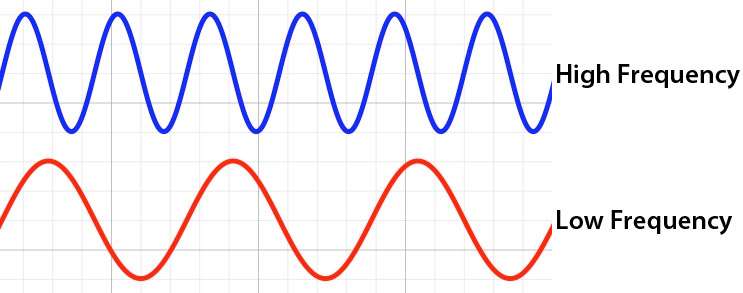

Another change proposed by the CBC initiative would be to equalize upload and download speeds. Presently, download speeds are generally higher than upload speeds, which is a convention in the industry. This is a legacy of the cable TV networks from which they evolved. Cable TV is primarily a one-way street datawise. The video information is sent from the cable provider to your home and displayed on your TV. Very little data is sent the other way, from your home back to the cable provider. This was true of most data streams in the early days of the internet as well. We downloaded pictures, videos and webpages. Nearly all the data was traveling in one direction. But this is changing. We now have Zoom meetings, smart houses and interactive TVs. We upload more information than we used to, which means upload speed is more important than ever. This trend is likely to continue in the years ahead as more of our lives become connected to the internet. The internet service proposed by the Broadband Committee and Axiom, the company contracted to provide the service, would equalize upload and download speeds. For example, the first tier of the service would offer speeds of 50 megabits up and 50 megabits down. This, combined with the other benefits outlined above, should make Zoom meetings much more bearable.

What about costs for the consumer? The first level service tier would offer speeds of 50 megabits download and 50 megabits upload for $54.99 a month. Higher level tiers would include 100/100 for $64.99/month, 500/500 for $149.99/month, and a gigabit line for businesses at a cost of $199.99/month.

Now that we’ve looked at some of the advantages and benefits of the fiber optic infrastructure proposed by the China Broadband Committee, what about the objections? A number of residents voiced their opposition to the project on my Facebook post, so let’s take a look at some of those objections.

One of the most common reasons people are against the project is because they think there are other technologies that will make the proposed fiber optic network obsolete or redundant in the near future. The technologies most often referenced are 5G wireless and Starlink, a global internet initiative being built by tech billionaire and Tesla/SpaceX CEO Elon Musk.

While new 5G cellular networks are currently being rolled out nationwide, it’s not clear when the technology will be widely available here in China. And even when such capability does become available to most residents, it will likely suffer from similar problems that our existing cell coverage suffers from now – uncertain coverage on the outskirts of town and in certain areas. (I still can’t get decent cell reception at my home just off Lakeview Drive, in China Village.) Further, while 5G is able to provide impressive download speeds and low latency, it requires line of sight with the broadcasting tower and can easily be blocked by anything in between like trees or buildings. Residents of China who currently suffer from poor internet service or cell phone reception today would likely suffer from the same problems with 5G coverage as well. Fiber optic cable installation to those residents would solve that problem, at least in terms of internet access, once and for all.

Starlink is a technology that aims to deliver internet access to the world through thousands of satellites in low-earth orbit, but it is still years away from reaching fruition and there is no guarantee it will deliver on its potential. When I spoke with the Broadband Committee’s Tod Detre, he said he applied to be part of the Starlink beta program more than six months ago, and has only recently been accepted (although he’s still awaiting the hardware required to connect). There is also some resistance to the Starlink project, primarily from astronomers and other star gazers, who worry how launching so many satellites into orbit will affect our view of the night sky. As of June, Starlink has launched approximately 1,700 satellites into orbit and currently services about 10,000 customers. The initiative is estimated to cost at least $10 billion before completion. At the moment, the company claims to offer speeds between 50 and 150 megabits and hopes to increase that speed to 300 megabits by the end of 2021, according to a recent article on CNET.com. To compare, copper-based networks can support data transfer speeds up to 40 gigabits, and fiber optic wires have virtually no limit as they can send signals at the speed of light. Of course, these upper speeds are always limited by the capabilities of the hardware at either ends of the connection.

While both 5G and technologies like Elon Musk’s Starlink hold a lot of potential for consumers, 5G service is likely to suffer from the same problems residents are already experiencing with current technology, and Starlink is still a big unknown and fairly expensive at $99/month plus an initial cost of $500 for the satellite dish needed to receive the signal. It’s also fairly slow even at the future promised speed increase of 300 megabits. As the Broadband Committee’s chairman, Bob O’Connor, pointed out at a recent public hearing on the proposed network, bandwidth needs have been doubling every ten years and likely to continue increasing in a similar fashion for the near future.

Another objection frequently voiced by residents is that the town government should not be in the business of providing internet service to residents. O’Connor also addressed this concern in a recent public hearing before the China selectboard. He said that residents should think about the proposed fiber optic infrastructure in the same way they view roads and streets. (This is a particularly apt comparison since the internet is often referred to as the “information superhighway.”) O’Connor says that although the town owns the roads, it may outsource the maintenance of those roads to a subcontractor, in the same way that the town would own this fiber optic infrastructure, but will be subcontracting the service and maintenance of that network to Axiom.

The Broadband Committee also points out that there are some benefits that come with the town’s ownership of the fiber optic cable and hardware: if residents don’t like the service they are receiving from one provider they can negotiate to receive service from another instead. The committee has said that although Axiom would initially be contracted for 12 years, there would be a service review every three years to see if we are happy with their service. If not, we could negotiate with another provider to service the town instead. This gives the town significant leverage to find the best service available, leverage that we would not have if the infrastructure was owned by a service provider like Spectrum or Consolidated Communications (both of whom have shown little interest in the near term for upgrading the China area with fiber optic cable).

There are certainly risks and outstanding questions associated with the committee’s proposal. Will there be enough subscribers for the project to pay for itself? Could another technology come along that would make the proposed infrastructure obsolete or less attractive in the future? Will proposed contractors like Axiom and Hawkeye Connections (who will be doing the installation of the physical infrastructure) provide quality and reliable service to residents long-term? Can we expect the same level of maintenance coverage to fix storm damage and outages that we experience now?

On the other hand, the potential benefits of the project are compelling. The internet, love it or hate it, has become an essential part of everyday life and looks only to become more essential in the years ahead. Having a reliable and high speed infrastructure for residential internet access is likely to play an important role in helping to grow China’s economy and to attract young families who are looking for a place to live and work.

Ultimately, voters will decide if the potential benefits outweigh the possible risks and pitfalls come this November.

Contact the author at ericwaustin@gmail.com.

More information is also available on the CBC website, chinabroadband.net.

Read all of The Town Line’s coverage of the China Broadband Committee here.

by Eric W. Austin

by Eric W. Austin