COMMUNITY COMMENTARY: My life with history

COMMUNITY COMMENTARY

by Bob Bennett

In all of the lives of human beings, the one factor that can never be changed is our history. It is there in all of its glory or shame. The deeds of those who came before us, and ourselves from the moment they are carried out, are forever in place. So, if it can’t be altered why is history important? The short answer to this question is that knowledge of the past, if used as a learning experience, can and should have a positive impact on those who are still alive and all of those who follow in our future. We should accept, but not repeat mistakes, live with the results but attempt to repair errors, and without question try and ensure that the faults and mistakes of our predecessors are not blessed or repeated. And yet, we all know that these ideas do not always occur; a perfect world does not and will never exist.

I have revered history throughout my entire life. This means that I started with the stories my dad told me when I was a toddler. He loved Zane Grey’s novels and knew a lot about the old west. When I was a couple of years older, my parents bought a full set of Colliers Encyclopedias, including the yearly update volumes, and I was really off and running. I would spend hours paging through those heavy books reading anything that caught my attention. Maybe this is a little over the top, but I loved every moment and learned tons of stuff.

Starting my secondary education in South Portland Junior High School in 1961, I was fortunate to have great history teachers all the way through high school. I wasn’t afraid to ask questions and at a time when many kids were bored with learning names, dates and places, I was in heaven. My freshman history teacher, Charles Cahill, had been in the OSS (pre-CIA) during World War II and even though he told us that he couldn’t really tell us what his actions involved, he could always keep us awake with his stories. Other teachers in high school were good, too, but it was in my college career at the University of Maine in Orono that I really “hit it big.”

My advisor and professor in a number of classes was Clark G. Reynolds. Dr. Reynolds had taught at the U.S. Naval Academy before arriving at UMO. He was the ultimate example of the teacher who knew the stories relating to history that made the classwork incredibly interesting. He had been closely involved with major World War II figures like Admirals Halsey and Nimitz and knew all of the details of their decisions and actions. He had also met many other players in the war. On December 7, 1970, he marched into our classroom with a Christmas card he had just received from a former Japanese naval officer, Minoru Genda, who had largely put together the attack on Pearl Harbor (December 7,1941); talk about timing! We’ll talk more about Dr. Reynolds later.

After college graduation in 1971, I began a 38-year career in education as a history teacher and also a 20-year semi-career in the 195th Army Band of the Maine National Guard. In both of these lives I was exposed to history in different ways. As a teacher, I was very consistent in relating what I was presenting to my students to events that had similarity to both the past and present. I tried to begin every single class session with at least a couple of current events, including something that had some relation to the history we were covering. Some days those events might take more time than I anticipated but I managed to get most everything on the day’s agenda addressed. As a member of an extremely well-regarded army band, I had the opportunity to travel to Puerto Rico, Canada and a number of American states. As a drum major leading a Mardi Gras parade in New Orleans, meeting and talking with Canadian World War II veterans at Gagetown, NewBrunswick, and seeing Robert E. Lee’s first Corp of Engineering project at Ft. Monroe, Virginia, were all great and eye opening experiences.

I moved from one school system to another, Portland to SAD #3 in 1978, got married in 1984 and it was at Mount View High School, in Thorndike, that I reconnected with Dr. Reynolds. One morning during a prep period I looked him up on line and found that he was at the College of Charleton, in South Carolina. On a whim I called the college, charging the cost to my home phone back then, and discovered that he was coming to Orono for a seminar in the following week. I set up a time to meet on campus. When I arrived at the building I went down the appropriate hallway, following the sound of his great, booming voice. When he concluded his presentation, we drove downtown to Pat’s Pizza and had a fantastic, several hour discussion about everything historic. This meeting helped confirm everything I felt about the value of history in one’s life and the need to keep up with all of its pieces.

As my teaching career continued, another opportunity arose and I switched to Erskine Academy, in South China. The location is just around the corner from where we live in South China; I walked to work most days rather than driving 50 mile round trips to Thorndike. While at EA, I was able to see a lot of history in a new part of the world. I chaperoned on five trips to Europe in my seven years teaching mostly Advanced Placement U.S. History. There really isn’t anything like walking through the U.S. Cemetery, in Normandy, and exploring Omaha Beach. The Colosseum, in Rome, is neat, too. When I retired in 2012, my formal teaching was done but I am a firm believer in “once a teacher, always a teacher.” I substitute taught and continued to pass on my knowledge ’till COVID arrived. I volunteered at the Boothbay Railway Museum and enlightened visitors with my wealth of railroad history.

Oh yeah, I forgot to mention that I am a nearly life-long model railroader. One of the best aspects of this hobby for me is the research into railroad history to build accurate models and scenes. To help other modelers, I have written more that 100 articles for various national publications, This has helped me stay active intellectually and to continue to share my ideas and passions, Also, in a rail-related venue, I was a summer conductor for 14 years on the Belfast and Moosehead Lake R.R. I shared tons of history with thousands of passengers during those times.

And so, this is my life exploring, enjoying and passing on history. The past is such a vital part of everyones’ existence and I really feel that ignoring it is almost inhuman. For parents, teach your kids about your past and experiences. For students, listen to your history teachers. Ask questions about what intrigues you and get involved in organizations that highlight learning about, and memories of what, has come before. It is absolutely true that once the ideas and memories of long ago are forgotten, they can never be recovered. It is our task to help preserve them forever.

This essay was composed to help inspire continued interest in and growth of the newly-resurrected China Historical Society.

by Elizabeth Byrd Wood

by Elizabeth Byrd Wood

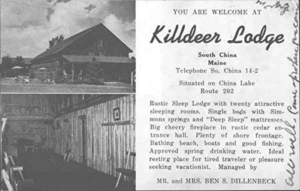

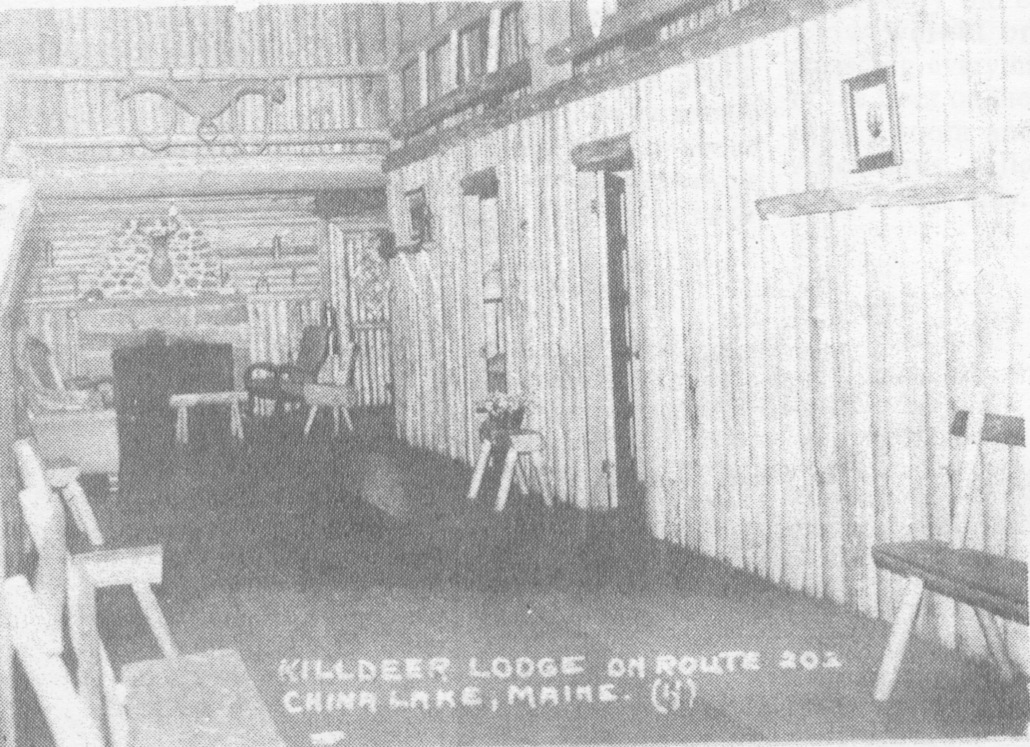

With the demise of the old Killdeer Lodge recently, which over the years had fallen into disrepair, the following article represents a history of the lodge, from its inception in 1929, to the razing in 2018.

With the demise of the old Killdeer Lodge recently, which over the years had fallen into disrepair, the following article represents a history of the lodge, from its inception in 1929, to the razing in 2018.