ERIC’S TECH TALK – My life in video games: a trip through gaming history

by Eric W. Austin

by Eric W. Austin

It was sometime in the mid-1980s when my father took me to a technology expo here in Maine. I think it was held in Lewiston, but it might have been some other place. (Before I got my driver’s license, I didn’t know where anything was.) This was at a time when you couldn’t buy a computer down at the local department store. You had to go to a specialty shop (of which there were few) or order the parts you needed through the mail. Or you could go to a local technology expo like we were doing.

They didn’t have fancy gadgets or shiny screens on display like you might see today. No, this was the age of hobbyists, who built their own computers at home. It was very much a DIY computer culture. As we walked through the expo, we passed booths selling hard drives and circuit boards. For a twelve-year-old kid, it wasn’t very exciting stuff. But then we passed a booth with a pile of videogames and my interest immediately piqued.

My father didn’t have much respect for computer games. Computers were for work in his view. Spreadsheets and taxes. Databases and word processing. But I was there for the games.

I dug through the bin of budget games and pulled out the box for a game called King’s Quest III: To Heir is Human. The game was released in 1986, so the expo must have taken place a year or two after that. The King’s Quest games were a popular series of adventure games released by the now defunct developer, Sierra On-Line.

Somehow I convinced my father to buy it for me, but when I got home I found to my disappointment that it was the PC DOS version of the game and would not play on my Apple II computer. I never did get a chance to play To Heir is Human (still one of the cleverest titles for a game ever!), but I never lost my fascination with the digital interactive experience of videogames.

The first videogames did not even involve video graphics. They were text adventure games. I remember playing The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy Game (first released in 1984), which was a text adventure game based on the book series of the same name by Douglas Adams, on a PC in the computer lab at Winslow High School. These games did not have any graphics and everything was conveyed to the player by words on the screen. You would type simple commands like “look north” and the game would tell you there was a road leading away from you in that direction. Then you would type “go north” and it would describe a new scene. These games were like choose-your-own-adventure novels, but with infinitely more possibilities and endless fun. Who knew a bath towel could save your house from destruction or that you could translate alien languages by sticking a fish in your ear?

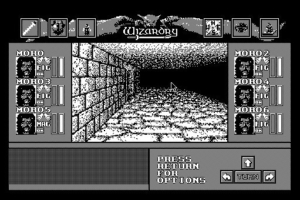

One of my first indelible gaming experiences was playing Wizardry VI: Bane of the Cosmic Forge (released 1990) in my father’s office on a Mac Lisa computer with a six-inch black and white screen. These sorts of games were commonly called “dungeon crawlers” because of their tendency to feature the player exploring an underground, enclosed space, searching for treasure and killing monsters. As was common for the genre at the time, the game worked on a tile-based movement system: press the forward key once, and your character moved forward one space on a grid. The environments for these types of games typically featured a labyrinthine structure, and part of the fun was getting lost. There was no in-game map system, so it was common for players to keep a stack of graph paper and a pencil next to their keyboard. With each step, you would draw a line on the graph paper and using this method you could map out your progress manually for later reference. Some games came with a map of the game world in the box. I remember that Ultima V: Warriors of Destiny (1988) came with a beautiful cloth map, which I thought was the coolest thing ever included with a game.

As I grew up, so did the videogame industry. The graphics improved. The games became more complex. As their audiences matured, games flirted with issues of violence and sexuality. Games like Leisure Suit Larry (1987) pushed into adult territory with raunchy humor and sexual situations, while games like Wolfenstein 3D (1992) had you killing Nazis in an underground bunker in 1940s Germany, depicting violence like never before. These games created quite the controversies in their day from people who saw them as corrupt indicators of coming societal collapse.

In 1996, I bought my first videogame console, the original PlayStation. At the time, Sony was taking a giant gamble, releasing a new console to compete with industry juggernauts like Nintendo and SEGA. The first PlayStation console was the result of a failed joint-effort between Sony and Nintendo to develop a CD-ROM peripheral for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), a console released in 1991 in North America. When that deal fell through, Sony decided to develop their own videogame system, and that eventually became the PlayStation.

There was a lot of debate during these years about the best medium for delivering content — solid-state cartridges, which were used for the SNES and the later Nintendo-64 (released 1996), or the new optical CD-ROMs used by Sony’s PlayStation. The cartridges used by Nintendo (and nearly every console released before 1995) featured faster data transfer speeds over optical CDs but had a smaller potential data capacity. Optical media won that debate, as the N-64 was the last major console to use a cartridge-based storage format for its games. Funnily enough, this debate has come full-circle in recent years, with the resurgence of cartridge-based storage solutions like flash drives and solid state hard drives. Those storage limitations of the past have mostly been solved, and solid state memory still offers faster data transfer rates over optical options like CD-ROMs or DVDs (or now Blu-Ray).

The PlayStation was also built from the ground up to process the new polygonal-based graphic technology that was becoming popular with computer games, instead of the old sprite-based graphics of the past. This was a graphical shift away from the flat, two dimensional visuals that had been the standard up to that point. This shift was an evolution that had taken place over a number of years. First, there was something called vector graphics, which were basically just line drawings in three-dimensional space. I remember playing a Star Wars arcade game (released 1983) with simple black and white vector graphics down at the arcade that used to be located next to The Landing, in China Village, when I was a kid. The game simulated the assault on the Death Star from the original 1977 movie and featured unique flight-stick controls that were very cool to a young kid who was a fan of the films.

Videogame consoles have changed a lot over the years. My cousin owned an SNES and used to bring it up to my house in the summers to play Contra and Super Mario World. Back then, the big names in the industry were Nintendo, SEGA and Atari. Nintendo is the only company from those days that is still in the console market.

Up until the late 1990s, each console was defined by its own unique library of games, with much of the development happening in-house by the console manufacturers. This has changed over the years so that nearly everything today is made by third-party developers and released on multiple platforms. In the early 2000s, when this trend was really taking off, many people theorized it would spell doom for the videogame console market because it was removing each console’s uniqueness, but that has not turned out to be the case.

Videogames are usually categorized into genres much like books or movies, but the genres which have been most popular have changed drastically over the years. Adventure games, usually focused on puzzles and story, ruled the day in the early 1980s. That gave way to roleplaying games (RPGs) through the mid-’90s, which were basically adventure games with increasingly complex character progression systems. With the release of Wolfenstein 3D from id Software in 1992, the world was introduced to the first person shooter (FPS) genre, which is still one of the most popular game types today.

The “first person perspective,” as this type of game is called in videogame parlance, had previously been used in dungeon crawlers like the Wizardry series (mentioned above) and Eye of the Beholder (1991), but Wolfenstein coupled this perspective with a type of action gameplay that proved immediately popular and enduring. Another game I played that would prove to be influential for these type of games was Marathon, an alien shooter game released in 1994 for the Apple Macintosh and developed by Bungie, a studio that would later go on to create the incredibly popular Halo series of games for Microsoft’s Xbox console.

One of the things I have always loved about videogames is the way the industry never sits still. It’s always pushing the boundaries of the interactive experience. Games are constantly being driven forward by improving technology and innovative developers who are searching for new ways to engage players. It is one of the most dynamic entertainment industries operating today. With virtual reality technology advancing quickly and promising immersive experiences like never before, and creative developers committed to exploring the possibilities of emergent gameplay afforded by more powerful hardware, I’m excited to see where the industry heads in the coming decades. If the last thirty-five years are any indication, it should be awesome!

Eric W. Austin writes about technology and community issues. Contact him by email at ericwaustin@gmail.com.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!