Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Palermo residents – Part 2

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

In case readers have not had enough genealogical confusion, this article continues with information about Palermo’s first three school committee members, elected in January 1805, and their families. Christopher Erskine, Stephen Marden and Samuel (or Samual) Longfellow were leaders among Palermo’s early settlers.

Millard Howard wrote that Erskine was in Palermo by 1788. In 1803, he owned 200 acres, when most landowners who had dealt with the Kennebec Proprietors (including Longfellow and Marden) had 100 acres.

Howard called Erskine “one of the most prominent citizens.” His Turner Ridge lot included some of the town’s “best farm land”; by 1801, he “was running a tavern” there. Erskine was the man charged with convening the Jan. 9, 1805, town meeting at Robert Foye’s house. He was elected town treasurer, as well as a school committee member.

This Erskine was most likely the one named on line as Christopher Erskine III, born Feb. 27, 1761, in Alna (Find a Grave), or Feb. 27, 1763, in Pownalborough (FamilySearch).

Find a Grave says his first wife, married Jan. 2, 1789, in Wiscasset, was Sarah Elizabeth Dickey (born Aug. 12, 1766, in Palermo). They had five sons and one daughter (Find a Grave) or five sons and four daughters (FamilySearch).

Find a Grave says the last child was Abiel Wood Erskine, born in 1806. FamilySearch calls Abiel, born May 9, 1806, the youngest son and says the last child was Cynthia, born on Nov. 3, 1808. She married, had at least seven children and died in February 1894.

Sarah Dickey Erskine died Nov. 10, 1818, in Palermo.

According to Find a Grave, on June 20, 1806, Christopher took as his second wife Ruth (Cox) Erskine, widow of William Erskine (1752 – 1800), of Bristol. (Neither William nor Christopher is listed as the other’s brother in any source your writer found.)

Where did Sarah go? And what about Cynthia, allegedly born to Christopher and Sarah two years after Christopher married Ruth?

Ruth Cox was born July 21, 1757, according to WikiTree. She married first husband William in 1776. Between 1777 and 1798, they had two daughters and five (Find a Grave), eight (WikiTree) or nine sons (FamilySearch).

When Christopher married Ruth on June 20, 1806, WikiTree says four of her sons were young enough to be at home. William, born in 1792 (no month given), would have been about 14; Robert, born Jan. 3, 1795, was almost 11 and a half; and twins Jonas and James, born June 27, 1798, were eight.

On Christopher’s side, FamilySearch says seven of his children by Sarah were under 15 on June 20, 1806. John was born Jan. 31, 1792; Sarah, Feb. 19, 1794; Elizabeth, Nov. 3, 1795; Henry, Aug. 28, 1798 (making him two months younger than his twin step-brothers); Alexander, Feb. 7, 1801; Rebecca, April 18, 1803; and Abiel, May 9, 1806, six weeks before his father’s remarriage.

Did Ruth’s children come with her? Or had she, widowed, given them up to someone better able to care for them?

Did Christopher’s children stay with him and their stepmother? Or did some or all go with Sarah, wherever she went?

How did the 11 children and two adults blend, if they did?

* * * * * *

Also on that 1805 Palermo school committee was Stephen Marden, probably the Stephen Marden (or Stephen Marden, Jr.), born Sept. 13, 1771, in Chester, New Hampshire, son of a Stephen Marden born in 1736.

Howard quoted at length from an account by Stephen’s younger brother, John (born Feb. 15, 1779), which was reprinted in Alan Goodwin’s earlier Palermo history. John wrote that in 1781, in New Hampshire, his father was killed by a falling tree, leaving a widow and eight children; a ninth child was born in September.

John came to Great Pond Settlement in the District of Maine in January 1793, when he was 14. He worked with Stephen until he was 22, when he bought his own farm.

Milton Dowe, in his Palermo history, added a third brother, Benjamin (the one born Sept. 29, 1781, WikiTree says). Dowe wrote that about 1800, the “iron parts of a water wheel” were sent from New Hampshire to Augusta, whence the three brothers brought them to Palermo to power a saw and a machine to build hand rakes (which they sold for 25 cents each).

If dates are accurate, Stephen Marden came with his new bride: WikiTree says he married Abigail Black (born Oct. 29, 1768) in Chester on Jan. 1, 1793.

One WikiTree page lists two children of the marriage, a daughter named Mary, born Sept. 19, 1795, and a son named Albra, born about 1812. Both died in Palermo, Albra on Nov. 16, 1877, and Mary (by then the widow of John Spiller, by whom she had had nine children) on Sept. 3, 1878.

Find a Grave says Stephen and Abigail’s children were Benjamin, born Oct. 26, 1798, and Albra, born April 12, 1812. This site has photos of Benjamin and Albra’s gravestones in Palermo’s Smith cemetery.

Another WikiTree page says Stephen and Abigail had 11 children, starting with a son named Stephen.

(Perhaps a generational mix-up? Find a Grave says Stephen and Abigail’s son Albra and his wife Hannah had eight sons and three daughters, born between 1838 and 1859. The fourth son, born in 1847, was named Stephen.)

Howard wrote that when the Massachusetts legislature, in February 1802, approved a plan to reconcile the Palermo settlers with the Kennebec Proprietors who sold the settlers their land, Stephen Marden was one of three Palermo commissioners chosen to determine how much the settlers owed.

Voters at the Jan. 9, 1805, town meeting elected Marden a school committee member, constable and tax collector. In his discussion of the meeting, Howard called Marden “one of the most prominent resistance leaders,” apparently meaning resistant to the Proprietors and supportive of the settlers.

Marden died on Feb. 2 or Feb. 7, 1825, and his widow, Abigail, on Sept. 26, 1834, both in Palermo. They, and John and his wife Eunice, are buried in Palermo’s Dennis Hill Cemetery (Find a Grave lists no Benjamin there).

Find a Grave says Stephen and Abigail’s son Benjamin bought John Spiller’s farm on Marden Hill. (By combining lists from two sources, an imaginative reader can make John Spiller Benjamin’s brother-in-law, husband of Mary.)

This site says the younger Benjamin was a farmer, a blacksmith and a “practical wheelwright” (builder of wooden wheels). It calls him “a man of more than usual intelligence and looked up to by his neighbors, who bore for him the highest respect.”

Find a Grave credits this Benjamin Marden with an interest in town affairs and an active role in organizing the town’s first library, “the Palermo and China Social Library.” Howard called the library organizer Benjamin Marden, 2nd, and said the library, opened “around mid-century,” was “apparently at his home on Marden Hill.”

* * * * * *

At that Jan. 9, 1805, town meeting that made Samuel Longfellow a school committee member, he was also elected meeting moderator and one of Palermo’s first three selectmen.

Longfellow was born in Hampton, New Hampshire, in 1756. He and his younger brother, Stephen, born in 1760, came to Palermo in 1788, Howard said.

Find a Grave says they were second cousins, twice removed, of poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Feb. 27, 1807 – March 24, 1882). Samuel served in the Revolutionary War from 1775 to 1779.

He married Mary Perkins (born July 5, 1759, in Kensington, New Hampshire) on March 28, 1779, in Kensington. Find a Grave names four children.

First was Mary “Polly,” born in 1781. In 1799 she married Samuel Fuller (1775 – 1853), by whom she had four daughters and a son between 1799 and 1820.

Second was Green, born Jan. 18, 1786, in Palermo. In 1805, Green married Sarah Jane Foy (1787 – 1848), with whom he had four sons and two daughters between 1809 and 1826 (Find a Grave) or eight sons and three daughters between 1806 and 1832 (Ancestry).

Find a Grave says Green had a second wife, Melinda Foster Fisher Palmer, born in Alna, Nov. 7, 1793. (Foster and Fisher were maiden names; her first husband had been John Palmer.) Melinda gave birth to a son and two daughters between 1826 and 1831; Find a Grave lists their last names as Palmer, not Longfellow (their names do not match the last three of Sarah’s children on the Ancestry list).

Find a Grave gives no marriage date for Green and Melinda, nor does it explain what happened to Sarah.

Howard wrote that in 1835, Green (maybe Green, Jr., born in 1811?) built Palermo’s District 2 schoolhouse, for $110. In March (1836?), district voters paid him $2 “for furnishing the room to keep school in the past winter.”

In 1847, two Longfellows, Green (probably Green, Jr.) and Dearborn (Green, Jr.’s brother, born in 1809), each had three students in the District 2 school.

Samuel and Mary’s third child was Jonathan Perkins Longfellow, born Dec. 15, 1795, in Palermo. Jonathan married Betsy Edwards (1799 – 1882); they had four sons (including another Samuel) between 1818 and 1837.

Fourth was Olive B., born in 1798. Find a Grave says she married twice. If dates are correct, her first husband, whom she married in 1841, was the Samuel Fuller who was her older sister Mary’s former husband. WikiTree says Mary died May 25, 1837.

Samuel died Jan. 3, 1853, and Olive married Capt. Edward Lawry, born in 1799. The Isleboro Historical Society’s on-line information says they married Dec. 2, 1853, in Searsmont.

Olive was Lawry’s second wife; his first was Pamelia W. Arnold (1804 – 1852), with whom he had two daughters and three sons in the 1830s and 1840s. The youngest son, Andrew, was listed in the 1870 census as a farmer in Searsmont, age 24 or 25, living with his father and stepmother.

* * * * * *

Two of Samuel and Mary’s granddaughters, Mary (Longfellow) Fuller’s daughters, married back into the Longfellow family. The second Fuller daughter, Louisa (born July 6, 1807), married Dearborn Longfellow, son of Green Longfellow and Sarah Jane Foy, in 1834 (according to FamilySearch, which gives her name as Leorina Louise Fuller).

Her older sister, Mary Louise (born Nov. 30, 1799), on May 15, 1823, married Nathan Longfellow, son of Samuel Longfellow’s brother and sister-in-law Stephen and Abigail.

Stephen Longfellow was born in 1760 in Hampton, New Hampshire. He and Abigail (born in 1766) were married May 3, 1785, in Newcastle; they had four sons and eight daughters, starting with Mary, born Aug. 10, 1785. (Mary was the Longfellow readers met briefly last week, who married John Cain.)

John and Mary’s son Page Cain/Kane, born Jan. 21, 1834, married Martha Longfellow on March 2, 1861. Martha was another of Samuel and Mary (Perkins) Longfellow’s granddaughters, son of Jonathan, born in Palermo in 1795, and his wife Betsy (Edwards).

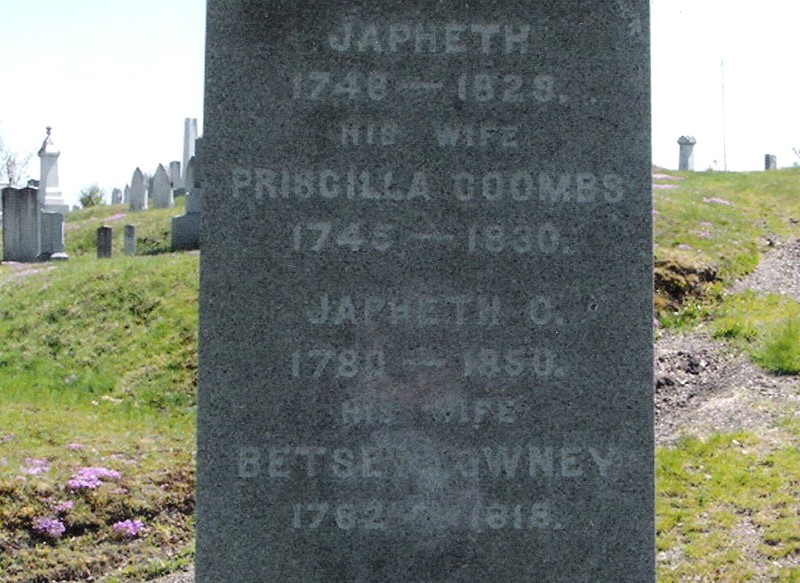

Stephen Longfellow died Jan. 31, 1834, and his brother, Samuel Longfellow, died Feb. 3, 1834. Stephen’s widow, Abigail, died May 13, 1843; Samuel’s widow, Mary, died April 6, 1849.

Samuel and Mary are buried under the same stone in Palermo’s Old Greeley Corner Cemetery, which also has graves of several descendants. Your writer did not find a burial location for Stephen or Abigail.

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1804 (1954).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Websites, miscellaneous.