Around the Kennebec Valley: Augusta education – Part 1

by Mary Grow

The town – now city – of Augusta was created on Feb. 20, 1797, when the Massachusetts legislature, responding to a local petition, divided the town of Hallowell.

The downriver third remained Hallowell. The upriver two-thirds became Harrington, renamed Augusta on June 9, 1797.

Harrington lasted long enough for voters to hold their first town meeting on April 3, where they raised $400 for education (and $1,250 for highways and another $300 for all other responsibilities).

In that first year, Captain Charles Nash wrote in his chapters on Augusta in Kingsbury’s 1892 Kennebec County history, Augusta officials re-created the eight school districts they inherited from Hallowell. Reflecting the current population distribution, numbers 1 and 2 were on the east side of the Kennebec and the other six across the river.

The traditional three-man district school committees continued, and in addition, Nash said, members of a seven-man town committee were expected “to visit schools,” presumably as overseers.

“This action was twenty-seven years in advance of statute legislation, and nearly a quarter of a century before Maine became a state and required it by law,” Nash commented.

A ninth school district was created in 1803.

James North wrote in his 1870 history of Augusta that 1803 was also the year that an “association of citizens” banded together to start the first post-primary school in town, buying shares to fund a brick grammar school building in the northwest corner of the intersection of Bridge and State streets, on the west side of the Kennebec.

(Bridge Street goes up the hill from the west end of the Calumet Bridge and intersects State Street at a right angle several blocks north of the state capitol complex. State Street roughly parallels the river.)

The building was finished in 1804, North said, and the association hired a Mr. Cheney (not further identified) as “preceptor” for a year, at a salary of $450. Courses included what Nash labeled “dead languages” (Greek and Latin).

Students were shareholders’ children, or children to whose parents a shareholder had “let” a share. Each share admitted one student.

North wrote that the school “flourished” until the building burned on March 16, 1807.

(Disastrous fires were not uncommon; in the next few pages North mentioned the Feb. 11, 1804, burning of a large Augusta building in which an early newspaper, the Kennebec Gazette was printed; the Jan. 29, 1805 (Nash said 1804), burning of the building that housed Hallowell Academy; the Jan. 8, 1808, burning of two adjacent blacksmith shops on Water Street; and the March 16, 1808, burning of the jail [a fire set by an inmate].)

By 1810, North wrote, Augusta was thriving; population and wealth had increased, and $1,000 was raised for schools (also $1,500 for roads and another $1,500 for “Poor and other necessary charges”).

Two years later, due to the War of 1812 with Great Britain, the Kennebec Valley economy was in distress. North talked about prices rising and stores closing, but he said nothing about the effect on education or other tax-dependent activities.

* * * * * *

North’s next educational reference was to 1815, when Judge Daniel Cony (see box) started building what looked like a house – but, North said, people asked why he wanted another house there? – at the intersection of Bangor and Cony streets on the east side of the Kennebec.

Adding a tower to the structure led to surmise that it was intended as a meeting-house for worship – and why did the Judge want a meeting-house?

When “seats and desks began to go in,” people concluded the building was a school. They were right; Judge Cony announced it would house Cony Female Academy. On Christmas Day, 1815, the Judge gave the building and lot to five men he had chosen as trustees; they organized themselves as a board on Jan. 5, 1816, and opened the school that spring.

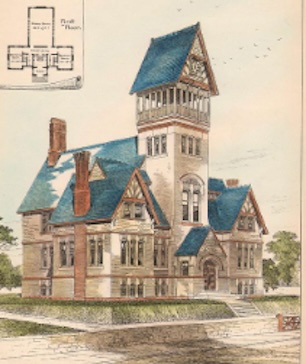

A picture of the building on line (at stcroixarchitecture.com) shows a three-story main block with a steeply pitched roof that provided space for a fourth floor. On each front corner was a two-story ell with third-story windows under its pitched roof.

The center of the front was a square tower topped with two levels of lattice-work under another steep roof two stories above the main roof. On the front of the base of the tower, a single-story entrance had another peaked roof, an arched door and two side windows.

The roofs were a medium blue, a contrast to the pale beige bricks. Medium-brown chimneys rose higher than the rooftops on the back of the main building and the side of each ell; the color matched the trim on the gables.

As Cony directed, his Academy offered free education to “worthy” orphans and other girls younger than 16. It also accepted tuition-paying students. North wrote that income soon covered expenses, and by 1820 Cony Female Academy “had a sum of money on hand in excess of expenses.”

Meanwhile, on Feb. 10, 1818, the Massachusetts legislature approved a charter for the Academy. In June of that year, North wrote, Cony gave the trustees a bell for the building; “maps and charts” for classes; and 10 shares in the Augusta Bank. He directed them to use five-sixths of the income from the bank shares to educate orphans and the remainder to buy prizes – medals or books – for “meritorious pupils.”

Kingbury wrote that 50 girls were Academy students in 1825. Their tuition was $20 a year; board was $1.25 a week.

In February 1827, North said, the by-then-Maine legislature gave the Academy a half township farther north in Maine (after an 1826 charter amendment gave the legislature a role in adding to or limiting the trustees’ powers). In February 1832 the trustees sold the land for $6,000.

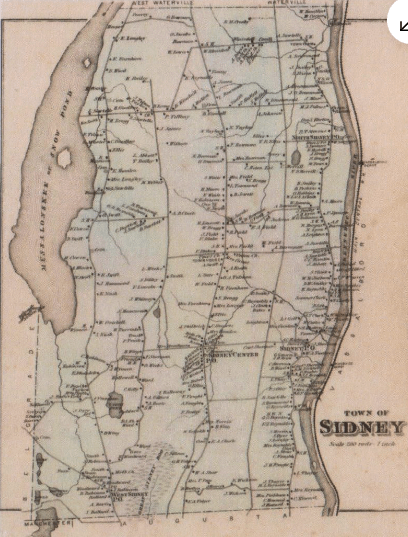

In 1827, a Bostonian named Benjamin Bussey donated land in Sidney, which the trustees sold for $500. That year, too, the trustees oversaw construction of a brick dormitory at the intersection of Bangor and Myrtle streets, two blocks north of the main building, which was still standing in 1870.

Another on-line site quoted an 1828 advertisement that listed courses offered: “orthography, reading and writing, arithmetic, grammar, rhetoric and composition, geography, History and Chronology, Natural History, Natural Philosophy and Astronomy, use of the globes, Drawing Maps, and also Drawing, penciling, and painting, and a variety of needlework.”

The school’s library, which in 1829 had 1,200 volumes, was “considered by some historians to be the best in the area at the time,” the stcroixarchitecture.com writer said.

The Academy’s second classroom building, after the school outgrew the original one, was the nearby former Bethlehem church at the intersection of Cony and Stone streets (built in the summer of 1827). The Academy trustees voted to buy it in November 1844 for $765; it, too was still standing in 1870. (They sold the original Academy building for $500, to Rev. John H. Ingraham, who made it into a house.)

North listed the Academy’s preceptresses and preceptors (teachers), usually one but occasionally two, over the years, starting with Hannah Aldrich in 1816 and ending with Mrs. Arthur Berry in 1857, the last year of operation. A minority were men.

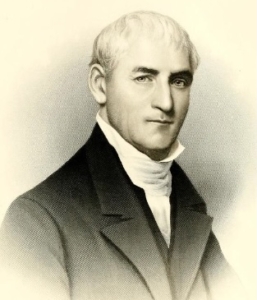

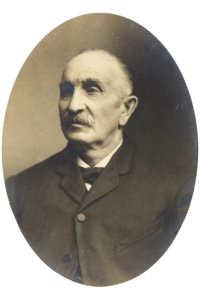

Daniel Cony

(See also the Feb. 23, 2023, issue of The Town Line.)

Daniel Cony (Aug. 3, 1752 – Jan. 21, 1842) was born in Stoughton, Massachusetts, south of Boston. He studied medicine in Marlboro, west of Boston, under Dr. Samuel Curtis.

When the British marched from Boston to Lexington on April 19, 1775, Cony was practicing medicine in Tewksbury, north of Boston (Find a Grave says Shutesbury, half-way across the state and therefore likely an error), and was a lieutenant in the local company of Minutemen. North reported that he was awakened at 2 a.m. by a knock on his door and the shouted message “American blood has been spilled and the country must rally.”

Cony and the rest of the company were on the way to Cambridge by sunrise; North did not say what they did there.

Later in the war, Cony served as adjutant in an infantry regiment (the 6th New Hampshire, according to Find a Grave) under General Horatio Gates, at Saratoga, New York, where, North wrote, he once led soldiers through an area commanded by a British battery to assist another company. He was present when British General John Burgoyne surrendered his army to Gates on Oct. 17, 1777.

Meanwhile, on Nov. 14, 1776, Cony had married Dr. Curtis’s niece, Susanna Curtis (May 4, 1752 – Oct. 25, 1733), in Sharon, Massachusetts. He left the army and in 1778 he and Susanna and their first daughter, Nancy (born in 1777), came to Hallowell, where his father, Deacon Samuel Cony, had moved the previous year and where Nancy died the year they arrived.

The couple had four more daughters (no sons): Susan (1781 -1851), Sarah (1784 – 1867), Paulina (1787 -1857) and Abigail (1791 -1875). All married local men.

Historians generally agree that Judge Cony created the Academy in appreciation of his own daughters and, since by 1816 all four were past school age, as a charitable exercise.

The family lived on the east side of the Kennebec. North said their second house, downhill from “the hospital” (the insane asylum) was still standing in 1870. Their third one, built around 1797 on Cony Street, burned in 1834 and was succeeded by “the present brick edifice on the same lot,” where Cony lived the rest of his life.

Cony practiced medicine in the area, was a member of the Massachusetts Medical Society and corresponded with other doctors, North said. In 1825-26, he was one of the founders of Augusta’s Unitarian Church.

He served as “representative, senator, and counsellor [member of the executive council]” in the Massachusetts legislature. Before 1820, he held judgeships in Kennebec County, Massachusetts. He was one of Augusta’s three delegates to the October 1819 Maine constitutional convention, and after statehood, was a Maine Judge of Probate until 1823, when he “resigned by reason of age.”

North wrote that until 1806, Cony frequently moderated Hallowell and Augusta town meetings. In 1830, after some years of not even attending them, he showed up – and was immediately and unanimously elected moderator. The meeting record showed a vote of thanks for “the able, impartial, and dignified manner in which he discharged the arduous duties of this day as moderator” at the age of 77 years and seven months.

In addition to creating Cony Female Academy, North wrote that Cony was “instrumental” in getting legislative charters for Hallowell Academy in 1791 and Bowdoin College in 1794. He was a trustee of Hallowell Academy and a Bowdoin overseer. He supported public education “by the exercise of a constant and healthful influence in its favor.”

Find a Grave displays Cony’s short death notice in the Augusta Age, published the day after his death. It mentions his Revolutionary service and goes on to describe him as a man who had “discharged various and important civil trusts, and was long and honorably connected with the settlement and growth of this section of the State.”

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Websites, miscellaneous.