Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Taking care of paupers

Bidding out was done at town meetings, where officials and voters discussed each needy person or family publicly by name. Residents bid for a poor person, asking a specific sum from the town for a year’s room, board and care, in the pauper’s home or the bidder’s home.

by Mary Grow

The earliest settlers in the Kennebec Valley, as elsewhere in New England, were for the most part able-bodied and self-supporting. But within a generation or two, a settlement would be likely to have residents who were unable to support themselves.

Some might be physically or mentally disabled. Older people might lose their ability to do manual labor and outlive their resources. Children might be left without a caring family.

A bad economy might send people into poverty. Different historians mention the near-destruction of export-dependent businesses (lumbering, for example) and the dramatic increase in prices of food and other necessities caused by the embargo during the War of 1812. Bad weather was another factor; farmers lost crops and income in 1816, the Year without a Summer.

Whatever the cause, if someone was a pauper and had no supportive relatives, caring for the poor was a town responsibility, as evidenced by the expression “going on the town” – becoming dependent on local taxpayers for the means of existence.

An on-line source says going on the town was a last resort and a humiliation. The writer gave three reasons: paupers lost the right to vote or to hold office; town officials might have authority to sell paupers’ property to fund their care; and townspeople looked down on those whom their taxes supported.

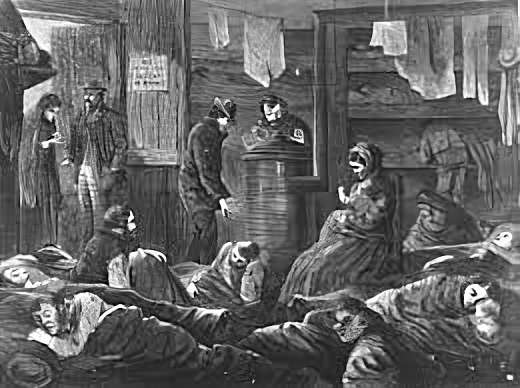

Maine towns had at least two ways of caring for their poor. One system was called “outdoor relief:” paupers were either supported financially on their own properties, or bid out to live with more prosperous neighbors.

Bidding out was done at town meetings, where officials and voters discussed each needy person or family publicly by name. Residents bid for a poor person, asking a specific sum from the town for a year’s room, board and care, in the pauper’s home or the bidder’s home.

An alternative was for voters to leave placement decisions to town officials. Officials for this purpose were the selectmen, whose titles included, and in many Maine towns still include, overseers of the poor.

The other option for a town was to buy a piece of property for a town poor house or poor farm, where paupers would be housed and cared for. “Farm” was almost always literal; the residents helped raise crops and tend livestock.

In her history of Sidney, Alice Hammond listed another method a person or family who owned property but was facing insolvency could use: the property could be deeded over to the town, on condition that the town would care for the donor(s) for life. Hammond mentioned real estate records showing Sidney had thus become owners of several farms that town officials later sold.

Town officials were careful not to spend their residents’ tax money on other towns’ paupers. Local histories occasionally mention lawsuits between towns to settle which is responsible for a person or family.

The following paragraphs will offer more specific information on how municipalities in the Central Kennebec Valley area took care of their poor before the present era of homeless shelters and homeless encampments.

This topic is one for which your writer’s self-imposed restriction to secondary sources available in books or on line (you’ll remember that this history series started early in the pandemic, when visiting town offices was discouraged) is limiting. Not all towns’ records are available on line, and some town historians wrote nothing about paupers. Others, however, provided enough information to intrigue your writer and, she hopes, her readers.

* * * * * *

At Augusta’s first town meeting, on April 3, 1797 (after Augusta separated from Hallowell in February 1797 and briefly became Harrington), Kingsbury reported that voters approved spending $1,250 for roads, $400 for roads and $300 for everything else, including supporting the poor.

The first poor house was approved at a March 11, 1805, meeting, according to Kingsbury and to James North’s Augusta history. Selectmen were not to spend more than $300. Voters at the annual meeting in 1806 elected George Reed or Read as its first superintendent.

Kingsbury described the location by 19th-century landmarks: north of Ballard’s corner (probably the current intersection of Bond and Water streets), and just south of the Curtis residence in 1805, and in 1892 marked by a “well on the east side of the road and an old sweet apple tree.”

By 1810, according to North, municipal spending had increased in the three categories Kingsbury listed in 1897: the appropriation for roads was $1,500, “payable in labor”; for schools, $1,000, and for everything else (both historians lump the poor “and other necessary charges”), another $1,500.

In 1833, North wrote, Augusta voters authorized selectmen to decide how to care for paupers. Neither he nor Kingsbury explained why there was evidently dissatisfaction with the poor house.

A special meeting in January 1834 made the authorization more specific: after the current contract with David Wilbur (the poor house superintendent?)) expired, town officials were to consider whether to buy a farm, contract or think up “some other mode.”

The five-man committee created to carry out this instruction reported at an April 21 meeting that while the legislature was in session they had talked with people from other parts of Maine and found unanimous support for “thePoor House system, both as regards economy and comfort and the prevention of pauperism.”

This committee recommended a second committee be appointed to look for “a suitable piece of land.” Charles Williams, from the first committee, and four new members of the second committee agreed with the first in advising that the farm be “near the village”; they recommended a third committee to buy a suitable property.

This third committee, which consisted of John Potter from the second committee and four more newcomers, reported to a Sept. 9 town meeting an agreement to buy Church Williams’ farm for $3,000. Their action was approved and yet another committee, chaired by Potter, appointed to build a house on the property.

The building went up by the end of 1834, North wrote. By 1870, he said, it had been “enlarged from time to time to the dimensions of the present commodious and convenient almshouse.”

A century after the building was finished, an on-line report on the Depression-era New Deal’s Federal Emergency Relief Administration’s work relief project describes repairs planned in 1934 and done in 1935. The writer said they were much needed: “Very few people realized the condition of this building and the unsanitary conditions and the inmates were living in.”

By then the building consisted of four floors over a large basement, “all of which were deteriorating rapidly.” Early steps were to reinforce a ceiling and put a partial new foundation “to keep the kitchen and range from falling into the basement.”

“The entire building was so infested with cockroaches and bedbugs that a special machine had to be hired along with an operator to exterminate these insects. All beds and bedding including blankets, mattresses, pillows and sheets were destroyed and replaced.”

Interior walls were replastered or repapered or painted; plumbing and heating systems were totally updated; the building was completely rewired; all the stairways were replaced, as were 20 doors and about 75 windows. A laundry was added and equipped, and a shed converted to a well-stocked store from which “the town truck delivers food daily to the city’s poor.”

The work crew consisted of 21 men. Total cost in labor, supplied by the ERA, was almost $5,400; the City of Augusta provided about $5,000 worth of materials. Work began Jan. 24 and was finished June 6, 1935.

The undated on-line site adds that the building had since been demolished and the Augusta public works department had moved onto the property.

* * * * * *

In Sidney, immediately north of Augusta on the west side of the Kennebec River, historian Hammond wrote, in the context of official town business in the 1790s, that “A problem right from the beginning was how to provide for the poor in town.”

She found an (undated) record of an early incident: the town constable “was ordered to serve notice on at least 25 families [presumably poor families] who had moved into town without first seeking permission.”

Town clerk’s records show that the constable carried out his orders, but, Hammond said, there is no proof the families were equally obedient; instead, some were still in Sidney years afterwards.

In addition to bidding out paupers, Hammond found Sidney town meeting voters repeatedly appointed a committee to buy a poor house or poor farm – and at the next meeting rejected the committee’s recommendation.

In 1867, she wrote, “the town actually purchased a working farm, hired a superintendent and moved paupers to the house.”

This poor farm was on 100 acres where Town Farm Road runs west off River Road (now West River Road) to Middle Road, in the north end of Sidney. The 1879 Kennebec County atlas shows the farm in the northwest corner of the three-way intersection; some of the land, then or later, was on the east side of West River Road (see below).

In 1869, Hammond wrote, voters directed selectmen to lay out and fence a cemetery on the town farm.

The 1877 town meeting warrant included an article Hammond quoted: “To see if town will vote to build suitable places at the poor house on the farm so as to be able to control the unruly poor.”

She also quoted the voters’ decision: “That it be left with the overseers to put them on bread and water if they see fit.” (Note the plural “overseers,” – by 1877, taxpayers were paying more than a single superintendent to staff the farm.)

This farm was a working farm, as Hammond’s information from what she called a typical inventory in the February 1895 annual report showed. The farm then had 28 hens; a dozen sheep; four cows and two yearlings; and two pigs. There were stockpiles of hay, straw, potatoes, turnips, oats, beans and beets.

The inventory further listed ham, pork, flour and butter; vinegar, pickles, molasses, spice and salt; and 80 gallons of cider and one pound each of tea and coffee.

Town officials and voters continued to debate whether the farm was the best arrangement, Hammond wrote. They agreed to lease it to different people, and eventually closed and sold it in 1919 to Mrs. Clara Wilshire for $3,000.

Hammond wrote that the sale did not include “the gravel bank on the east side of the River Road.” J. J. Pelotte later bought that parcel for $1,000. (Sidney’s 2003 comprehensive plan, found on line at the University of Maine Digital Commons site, lists the J. J. Pelotte gravel pit.)

Main sources

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870)

Websites, miscellaneous.