LIFE ON THE PLAINS: Christmas on The Plains

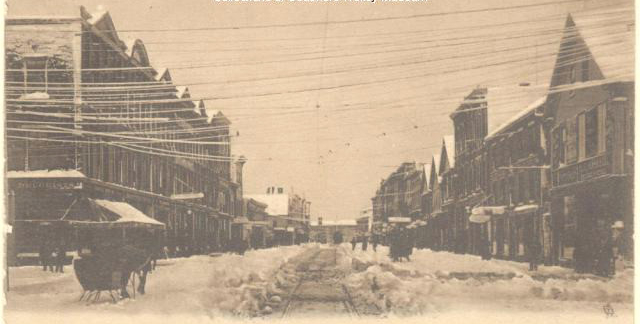

Water St., Waterville, The Plains, circa 1930. Note the trolley in the center of the photo. The trolley ceased operations on October 10, 1937. Many of the buildings in this photo are no longer there. (photo courtesy of Roland Hallee)

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

Growing up on The Plains in the ‘50s and ‘60s saw many changes when it came to Christmas.

My early memories included going out with the family one evening to a lot and picking out a Christmas tree. My dad took it home, set it up on a homemade stand, and commenced to reconfigure Mother Nature’s creation.

That consisted of cutting some excess branches from one side, drilling a hole in the trunk in some bare areas, and inserting the cut branches. He did this until the tree was symmetrical. Then we decorated it.

That went on for several years, until my mother decided she had had enough with decorating, and my dad didn’t want to do any more spruce cosmetic work.

They bought an artificial tree. It was nothing like today. This tree was silver. Completely artificial and commercial. There was a light that would set on the floor behind, with a flood light, that had a multi-colored wheel that would rotate – blue…yellow…green…red, etc.

That tree was set up in the living room. Christmas was held on Sunday, after church, while my mother would prepare the Christmas dinner, of roast beef, mashed potatoes, vegetables, rolls, you get the picture. Our grandparents, who lived next door, always came, too.

As we grew older, things changed again. Now, my dad had finished a portion of the basement into a “rumpus” room. That is where the artificial tree was set up. But, come Christmas, there were more changes. My mother didn’t want the hustle and bustle of Christmas day, so it was off to midnight Mass on Christmas eve. Afterwards, mom would warm up the tourtère pies, and we would have the distributing of Christmas gifts at that time. Of course, until we were old enough to attend the midnight Mass, we had to wait at home until the adults returned. Again, the grandparents were present.

Following the holidays, when we had a real tree, my mother was meticulous in taking down the Christmas tree, making sure every last piece of tinsel was removed before it was put out to the street for the annual city Christmas tree pickup.

When I was about nine years old, my parents went out one evening and left us four boys at home – my oldest brother was old enough to babysit. While rough-housing with my younger brother, we discovered Christmas gifts “hidden” behind the couch. So much for Santa.

But, as much as Christmases are always special, especially once my wife and I raised our two children, enjoyed the day with our grandchildren, and now experiencing Christmas with our great-grandchildren, Christmases are even more special.

But the memories of Christmas on The Plains in the ‘50s and ‘60s will always have a place in my memory.