John F. Kennedy (AI generated)

John F. Kennedy

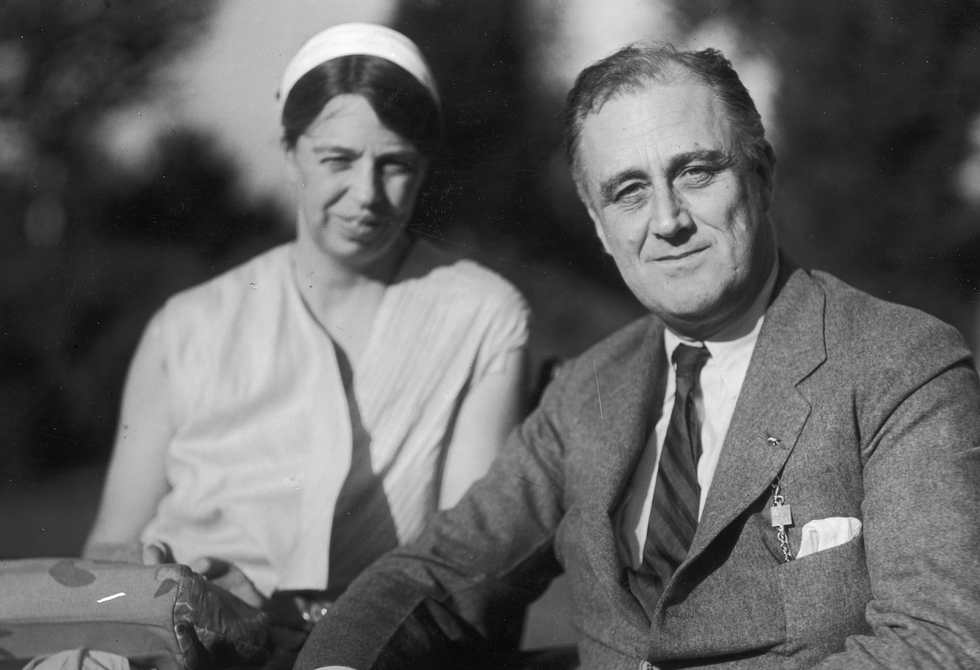

The 35th President John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963) was a most vivid, vibrantly alive presence on the family Philco TV set from when I first saw him debate Richard Milhous Nixon (1913-1994) during October 1960, it being a very cold Friday night, to the assassination in Dallas; I remember Kennedy’s highly strong Irish Boston accent and debonair appearance versus Nixon’s coarse bass speaking voice and the derailing 5 o’clock shadow.

On Election Day in 1960, my 4th grade East Vassalboro School teacher Susan Brondmo all but declared Nixon the winner and everyone in class applauded, except one girl whose family was both Catholic and Democrat. The following day when the Illinois vote came in, she was the only one smiling.

Key events during Kennedy’s 1,000 days in office have been chronicled in detail – the inaugural ceremonies with Robert Frost reading a poem for the occasion (Frost was a dyed in the wool Republican and a huge fan of Eisenhower but was thrilled to be invited by Kennedy that freezing snowy day in January 1961); the Bay of Pigs fiasco; First Lady Jackie’s televised tour of the White House; the enrollment of the first African-American student, James Meredith, at the University of Missisippi, with the National Guard called in; the, for me personally, nightmarish week of the Cuban Missile Crisis; Kennedy’s phenomenal charm at his press conferences; and finally November 22, 1963.

One occasion just a month before Dallas was Kennedy’s visit to the University of Maine/Orono when Dr. Lloyd Elliot was president there and which I watched on TV.

A 1975 book, Conversations With Kennedy, by former Washington Post editor Benjamin C. Bradlee (1921-2014), provides fascinating anecdotes of a close personal friendship between the two men and their wives, beginning in 1958 when Kennedy was still a Senator and he and Bradlee were neighbors.

A few examples:

Early in his campaign, Kennedy admitted to feeling strange about running for the Oval Office himself but then stated that “I stop and look around at the other people who are running for the job. And then I think I’m just as qualified as they are. ”

Joe Kennedy Sr. was testily against his son running in the 1960 West Virginia primary because of its hostility to Catholics. Kennedy ran anyways and won; he and Jackie invited the Bradlees to fly from D.C. to Charleston for a victory celebration and the very bumpy ride terrified Bradlee’s wife Tony and JFK’s sister Jean Smith who kept screaming for her husband Steve.

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, Kennedy consulted with Nixon, with whom he had similar views about the Cold War, but expressed relief that Nixon wasn’t president at the time.

Kennedy was friendly with Ed Muskie and the two went sailing off the Maine coast. He loved the ocean but otherwise preferred city life to the countryside.

As overnight guests at the White House, the Bradlees once witnessed the president wandering around in his night shorts wondering aloud what life was like in that mausoleum known as the Kremlin while the couples were watching an NBC special on it.

Kennedy had a deep admiration for Vice-President Johnson’s talents as a political sharpshooter but found LBJ’s presence at times creepy.

Kennedy sometimes enjoyed listening to gossip on other politicians.

Adlai Stevenson’s reputation as an intellectual may have been overrated. Kennedy read 10 books for every one that Stevenson read.

During the weekend when the country was grieving, Bradlee and his wife were at the White House and witnessed long time Kennedy family friend Dave Powers helping to assuage Jackie’s grief at odd moments with stories of hilarious moments during the 1960 campaign, but then the tragedy would intrude again from the TV coverage and all the other details.

The concluding paragraph – “Jackie was extraordinary. Sometimes she seemed completely detached, as if she were someone else watching the ceremony of that other person’s grief. Sometimes she was silent, obviously torn. Often she would turn to a friend and reminisce, and everyone would join in with their remembrance of things forever past. There is much to be said for the wake. Led by Dave Powers, this one was more often than not surprisingly cheerful, and always warm and tender. “

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates