PAGES IN TIME: Ice harvesting

by Richard Dillenbeck

by Richard Dillenbeck

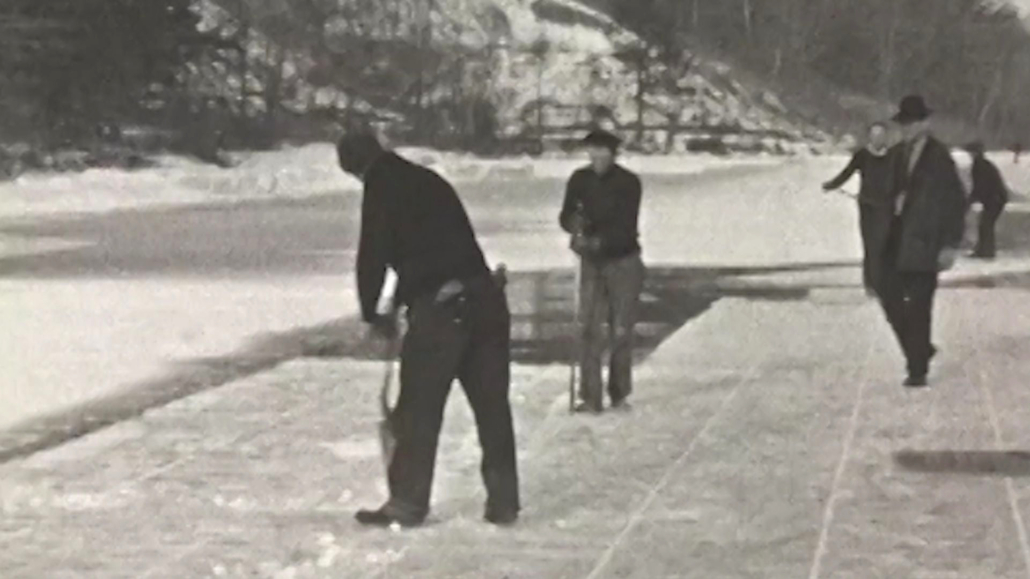

Another normal part of life was “putting up ice” in our ice house located behind the barns. In January and February, the ice in China Lake averaged 20-22 inches thick. Ice was necessary in some rural Maine homes because iceboxes were still used by families without electric refrigerators. My father and I would go down to the South China landing to observe the harvest of ice.

Snow had to first be removed from the frozen lake surface. Cutting was done by hand and started at a hand drilled hole made by a big hand-powered auger, big enough to allow the saw blade down through the hole. I haven’t seen one since, but the big-toothed saw was a good four feet long and had a T-shaped handle attached perpendicular to the blade, allowing the man doing the sawing to slowly walk backwards as he cut the ice.

Each worker had his own way of sawing, but basically it was done with the saw at an angle and it was heavy enough to bite through the ice. Several parallel cuts were then made, followed by cuts made at 90 degrees to the first, thus freeing the blocks of ice.

Removing the first block of ice was tricky but usually they would push the ice block down in the water and it would bob up high enough for another worker to grab it with big ice tongs. The next would come out easier because it was free on both ends and the tongs could grab it. Big, heavy five-foot long ice chisels with a wide blade helped free blocks. The well over 100-pound blocks of ice were then dragged off by other workers with ice tongs and pulled up a ramp onto a truck for delivery to ice houses around the area, including ours.

There may still be ice houses standing somewhere in our northern states but, for the most part, they were a symbol of rural Maine that is gone forever.

Ice houses didn’t have floors. A layer of sawdust started the process at ground level. That thick layer of sawdust was always the first step in preparing for the delivery of ice. The ice blocks were slid down a ramp into the icehouse and carried by tongs to their place, each separated by at least an inch of sawdust and then the whole layer covered with it. Each block had sawdust stuffed between the blocks, otherwise they would freeze together.

The first layer of ice, after being covered with sawdust, would receive the next layer of ice, also covered with a layer. This was repeated until the icehouse was full. The front opening of the icehouse through which the blocks were pulled, was close to nine feet tall and made like a Dutch door with an upper and lower section. A fixed wood ladder ran up the ice house wall next to the doors. The reader can well imagine, it was easy to bring the blocks into the ice house for the first few layers, but when the ramp reached up higher than the truck bed, they had to be dragged upwards on the ramp.

The driver of the truck helped move the ice into the ice house. I was not strong enough to handle the blocks during the few years we “put up ice,” so my job was to spread sawdust. When summer approached, I sold ice if my father was not around. In late spring and summer, owners of several camps around the lake would come every week for a fresh block of ice. Towards the end of summer, the blocks had melted a lot and were easier to handle.

We only did it for two or three years. By then, everyone had electric refrigerators.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!