PFAS: The “forever chemicals” making more headlines

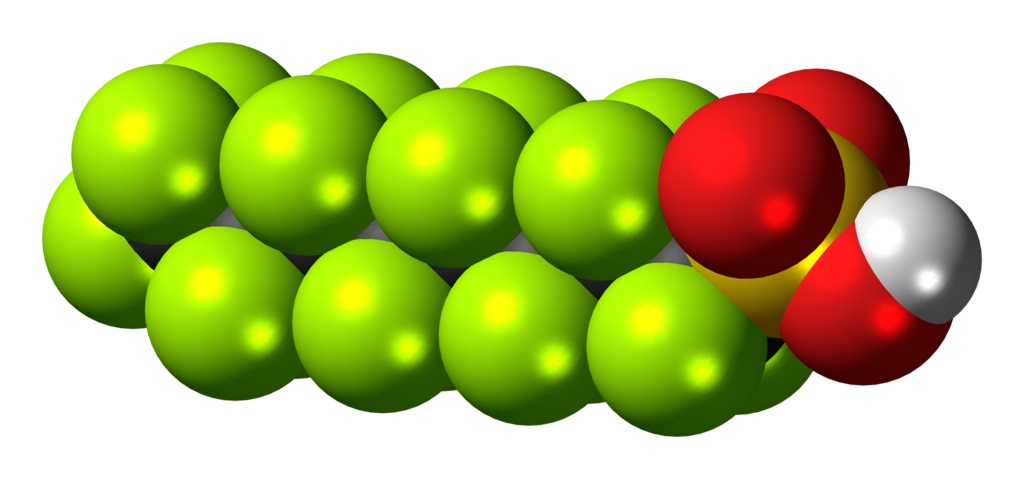

Space-filling model of the perfluorooctanesulfonic acid molecule, also known as PFOS, a fluorosurfactant and global pollutant.

by Pam McKenney

Many of you may have recently seen an article posted by the Town of Palermo about PFAS, or “forever chemicals,” and learned that the DEP would be investigating sites in our town. During the fall of 2021, you may also remember local headlines like this: “Toxic Water in Fairfield: Residents with drilled wells deal with sky high levels of PFAS.” PFAS are man-made chemicals known as per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances. They are a byproduct of plastics that resist degradation to the extreme that they are referred to as “forever chemicals.” They are linked to a number of health problems, and they are showing up in our well water and in our food supply. According to a Fairfield-area DEP investigation fifty-two wells were tested and found contaminated, some with rates as high as 1800 parts per trillion (new legislation calls for 20 parts per trillion as safe).

The article on the Town of Palermo site, composed by the Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), asserts that this is not just a Fairfield problem. Truth is: PFAS are everywhere, from the peaks of Mt. Everest to the bottom of our oceans, including Palermo. The Maine Department of Agriculture first identified the problem in Fairfield through a milk test from a local dairy farm. Further testing revealed the chemicals existed in drilled well water, chicken eggs raised in infected sites, and even prompted the Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (IF&W) to issue a “Do Not Eat” advisory for areas in Fairfield when excessive levels of PFAS were found when five of eight harvested deer were tested.

By their very nature, PFASs are here to stay and will be showing up in more headlines and in human bloodstreams. The post on the Town of Palermo website “A Brief History of PFAS (in Palermo)” Town of Palermo website, outlines Palermo’s status with this toxic substance. It is necessary to educate ourselves about the thousands of chemicals in PFAS and limit our exposure from products like: grease-resistant paper, fast food containers/wrappers, microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, and candy wrappers, nonstick cookware, stain resistant coatings used on carpets, upholstery, and other fabrics, water resistant clothing, and fire retardant materials. Because PFAS are at low levels in some foods and in the environment (air, water, soil, etc.) completely eliminating exposure is unlikely according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR).

Although these products contribute to contamination, the most common way in which PFAS can infiltrate groundwater in Maine is through the spread of sludge and septage on fields. The DEP defines these materials as:

- sludge; a byproduct of wastewater treatment and waste from pulp and paper mills.

- septage; a fluid mix of sewage solids, liquids, and sludge of municipal origin.

When you call to have your septic system pumped, it must be disposed of. Wastewater treatment plants do not store treated materials indefinitely; it has to go somewhere. The volume of sludge and septage production is prodigious and must be managed properly.

The Maine Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) offers an online map that charts the locations of approved land application sites and updates as more information becomes available. Among the hundreds of identified locations in Maine, this map shows three licensed application sites in Palermo, but the DEP cautions that “not all locations statewide were utilized and site status will be confirmed based on actual spreading records.” Testing for PFAS is complicated and expensive and currently has to be sent out of state for results, however, test kits are available through DEP. Additionally, fish test results from dozens of Maine lakes are reported on the map. Being from Palermo, I noted that a 2014 test result derived from a “skinless filet” was found to have the chemical PFOA (Perfluorooctane sulfonamide, PFOA info). It is unclear who collected the sample and why, although the “concentration level” was listed at “0.0.” A conversation with Mike Jakubowski at ME DEP indicated that this is a collaborative effort among departments and “testing of Tier One sites may extend through the end of 2023.”

The DEP has categorized one sludge application site in Palermo as a “Tier One” location, which means it will be investigated and sampled. A Tier One site has specific criteria: involves the application of 10,000 cubic yards or more of sludge to the land, have homes within a ½ mile of the application, is likely to have PFAS in the sludge based on the sources and contributors of the sludge. While the material used in Palermo was similar to the Fairfield sites, the volume applied was substantially less: over 147,000 cubic yards in Fairfield, but only about 5,000 cu/y here, and only for a period of about five years, from 1997-2002. The DEP website includes a table with dozens of Maine towns currently identified as areas with the need for immediate testing. Despite these concerns, according to current laws and regulations, DEP can test land and water “by permission only,” and the spread of septage and sludge continues to be permitted through the DEP.

So who is responsible for the problem? These chemicals get into our air, water, and soil through human consumption. Consumers assume that these FDA-approved products are safe, that testing and regulation makes the spread of sludge safe. It is not safe and we continue to understand how to limit exposure and minimize the damage.

Manufacturers like 3M and Dupont have known for decades the potential risks and toxic effects of PFAS. Areas of our country where these and many other chemical companies operate are highly contaminated and municipalities are seeking compensation for clean up and for legislation to hold corporations accountable. Here is recent testimony related to PFAS for the Committee on Government Oversight and Reform. I also recommend the documentary The Devil We Know concerning Dupont and PFAS contamination. Organizations like EWG (Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization) provide information and support these efforts for reform and action. For more about the illnesses that may be linked to exposure, consider these sites: EPA website and Natural Resources Defense Council.

We will be forever living with these “forever chemicals.” Although the human body is an amazing structure of systems that can tolerate exposure to an array of substances, there are things we can do to coexist with PFASs as safely as possible. We can stop assuming products are safe and demand rigorous, responsible government oversight. We can resist attitudes that value deregulation and promote corporate profit over human life and environmental protection. We can support citizens and community activists who seek change and advocate for research. We can educate ourselves. Here are further actions recommended by various biomonitoring sites.

- Include plenty of variety in your (and your child’s diet), and limit foods in grease-repellent wrappers and containers.

- Avoid products labeled as stain- or water-resistant, such as carpets, furniture, and clothing.

- Check labels of household and personal care products; avoid those with “fluoro” ingredients. Contact the manufacturer if you can’t find the ingredients on the label. Demand safe products and testing. Boycott those that are questionable.

- If you choose to use protective sprays, sealants, polishes, waxes, or similar products, make sure you have enough ventilation and follow other safety precautions.

- Because PFASs can come out of products and collect in dust: Wash your and your child’s hands often, especially before preparing or eating food. Clean floors regularly, using a wet mop or HEPA vacuum if possible, and use a damp cloth to dust.

- Contact DEP if you have concerns about your drinking water or live less than a half mile from a site with a history of sludge spread. Request a test.

- Contact your legislator to support action aimed at zero exposure and support LD1911 which refines “loading rate” calculations (that amount of PFAS allowed in treated materials). Testimony from Maine hearing 1/24/22 discussing LD1911-concerning PFAS in Drinking Water .

- To prevent PFAS and other toxins from entering groundwater, avoid flushing or improperly disposing of chemicals and pharmaceuticals. These toxins do not disappear when they go down the drain.

Above all, strive to be involved and work to preserve our towns and our world for future generations.

Pam McKenney, a Palermo resident, is a free lance writer, and teacher at Erskine Academy, in South China. She currently serves on the board of directors of the Sheepscot Lake Assn., and is not associated with any agencies or organizations mentioned in the article. She may be contacted at pamckenney@yahoo.com.