Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Libraries – Continued

by Mary Grow

Lawrence Library, in Fairfield, described to readers last week, is one of three libraries in the central Kennebec Valley whose buildings are on the National Register of Historic Places. The other two are Lithgow Public Library, in Augusta, this week’s topic, and Brown Memorial Library, in Clinton.

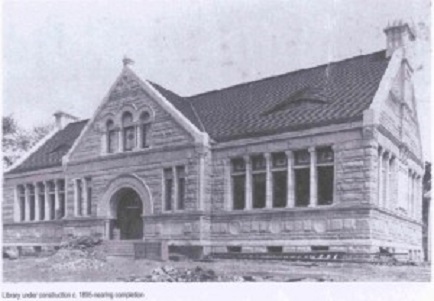

The cornerstone for the building housing Augusta’s Lithgow Public Library was laid in June 1894, and the library opened in February 1896. The building was added to the National Register on July 24, 1974, before the first of two twentieth and twenty-first century expansions.

As mentioned last week, in earlier years Augusta had the Cony Female Academy library, started in 1815. Henry Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that Cony’s initiative led to the 1817 organization of a “reading room and social library association.”

This group was reorganized June 2, 1819, and incorporated June 20, 1820, as the Augusta Union Society, which “collected a large library.” When it disbanded (Kingsbury gave no date; James W. North, in his history of Augusta, described nothing later than its sixth anniversary celebration in October 1825), its books were passed on to the Female Academy.

After that institution closed in 1857, Kingsbury wrote that its library “became considerably dispersed.” Eventually, he said, some 800 of its books, including one from 1612, ended up with the Kennebec Natural History and Antiquarian Society, organized in 1891.

(The Natural History and Antiquarian Society was the direct ancestor of today’s Kennebec Historical Society, headquartered at 61 Winthrop Street in Augusta. A KHS history found on line says in 1891 the organization invited donations of “botanical collections” and “birds and animals for mounting,” as well as print materials.

In 1896, the society moved its collection to the newly-opened Lithgow Library, where it stayed for many years. Today, the historical society has no natural history collection, but its premises are full of old maps; newspaper articles; business, school and personal records; photographs; and similar information.)

Meanwhile, 50 Augusta residents organized the Augusta Literary and Library Association, chartered by the Maine legislature in 1873. Each charter member gave $50 to buy books; other residents donated more books, to a total of around 3,000 within a few years, Kingsbury wrote.

The Association and its library were first housed on the second floor of the Meonian Hall on Water Street. This building was the second Meonian Hall; James North (presumably the same man who wrote the Augusta history in 1870) built the first one in 1856 and named it after Maeonia (an ancient city at the eastern end of the Mediterranean; the area is now part of Turkey). It burned in the great fire of 1865 and was promptly rebuilt.

Association members, men and women, met in each other’s houses to discuss books. The Association “provided the city with a library, a reading room and literary and scientific lectures,” according to an on-line site.

Earle Shettleworth, Jr., the Maine Historic Preservation Commission official who nominated Lithgow Library for the National Register of Historic Places, listed James G. Blaine’s family and Maine governors Joseph Williams, Lot M. Morrill and Seldon Connor as Association supporters. Williams and Morrill governed in the 1850s, Connor in the 1870s.

Despite a promising start, Shettleworth’s research confirmed Charles Nash’s history of the Lithgow Library (quoted in an on-line site) as saying the society was soon in financial difficulty. Members voted to sell the books and close down. (The international financial panic that started in 1873 might have played a role).

However, Nash wrote dramatically, one of the leading members, James W. Bradbury, “was in possession (as counsel and attorney) of confidential knowledge of great weight in connection with the matter.” Bradbury persuaded the rest of the members to rescind their vote by offering free space for the book collection in a Water Street building.

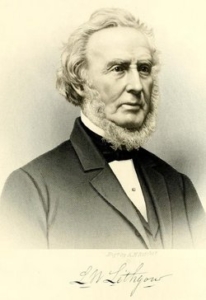

What Bradbury knew was that another Association member, Llewellyn Lithgow, had willed $20,000 to the City of Augusta to build a public library. Lithgow was born Dec. 25, 1796, in Dresden; he moved to Augusta in 1839 and did so well in business that he was able to retire when he was 40.

Lithgow died suddenly on June 22, 1881. His will became public knowledge, and City officials accepted the funds for the intended purpose. Later, Kingsbury wrote, the City received another $15,000 as one of Lithgow’s residuary legatees.

In February 1882 the new trustees of the planned Lithgow Library and Reading Room consulted the Literary and Library Association trustees, and the two groups merged. A new library building, to be named in honor of Lithgow, was one of their first goals.

The trustees bought the Winthrop Street lot where the library stands in 1888 and adjoining land in 1892 and started raising more money. Shettleworth wrote they aimed for $40,000; by the fall of 1892 they had $22,000. They wrote to Andrew Carnegie, who was famous for supporting libraries, asking for help.

On Nov. 15, Shettleworth wrote, Carnegie promised half the remaining $18,000 if the trustees provided the rest. They did, within six months, and Carnegie fulfilled his pledge.

A nation-wide competition to design the new building attracted 65 entries (Nash) or 69 entries (Shettleworth). Review began on July 15, 1893. Trustees found that some of the plans were too elegant to be affordable, many did not meet their requirements and only a handful were worth considering.

After two months, Shettleworth wrote, they chose Neal and Hopkins, an architectural firm in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Joseph Ladd Neal was a Wiscasset native who worked in Boston and New York before settling in Pittsburgh around 1892. His partnership with S. Alfred Hopkins lasted only a year, according to Wikipedia, or three years, according to Shettleworth.

Neal’s preferred architectural styles included Richardsonian Romanesque (similar to Lawrence Library architect William Miller’s taste, mentioned last week). Shettleworth wrote that Lithgow Library is significant as “Maine’s purest expression of the late nineteenth century Romanesque Revival fostered by H. H. Richardson.”

When Kingsbury published his history in 1892, the new library building was still in the future. He wrote that the Water Street rooms had more than 400 patrons, who were charged a dollar a year to check out books; the reading room was “well patronized”; and Miss Julia Clapp had been librarian since 1882.

Shettleworth found that construction of the new building started in the spring of 1894. It was finished in January 1896. Total cost of the building and land was $51,850, according to an on-line site.

A history of the Augusta Masonic Lodge (the book is in the Maine State Library; this writer found it on line) describes the June 14, 1894, laying of Lithgow Library’s cornerstone, as part of a cornerstone-laying ceremony for the Masonic Hall on Water Street.

The history says 500 people participated in a parade that started on Water Street; went to the Capitol building to be reviewed by Governor Henry B. Cleaves; “countermarched” to the Augusta House for another review by Cleaves, the state’s executive council and Masonic dignitaries; went to the corner of State and Winthrop streets, where Horace H. Burbank, Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Maine, laid the library cornerstone; and finally headed back down to Water Street, where Burbank and others laid the Masonic Hall cornerstone.

An open house on Feb. 3, 1896, welcomed residents to the new library. They saw a story and a half tall building – Richardson’s response to the 1870s and 1880s demand for library buildings for small communities, Shettleworth said – with exterior walls of rough gray granite (Norridgewock granite, according to an on-line history) and finished granite detailing.

The long front (south) wall had a protruding gable-roofed entranceway flanked on each side by five tall rectangular windows, their top sections stained glass. Under the first, third and fifth windows were circles of smooth stone, each with the name of an “important literary figure.”

Under the gable, finished-granite steps led to the entrance door, which was recessed in a “large Romanesque arch” of smooth granite.

The arch was flanked on each side by two vertical stained-glass windows and a “semi-detached Romanesque column,” Shettleworth wrote. Above the arch were the words “The Lithgow Library,” and above that a trio of windows “surrounded by finished Romanesque arches and semi-detached columns.”

East and west walls had six stained-glass windows on the ground floor. They were arranged in threesomes separated by Romanesque panels, with solid wall between the threesomes.

The central wall area on the west side was rough granite. The middle of the east wall, facing toward State Street, was decorated with a “large square panel containing many names of writers” and on a lower level more writers’ names in circular panels.

The half-story above each end wall was of granite “cut in a variety of decorative patterns.” A chimney topped each end; on the east, the date 1894 was added “near the peak of the gable.”

The back (north) wall resembled the front, Shettleworth wrote, except that the entrance on the front was replaced with “three bays of stained glass windows on either side of a chimney,” with “[t]hree circular author panels” in each bay.

The ground-floor layout inside was what Shettleworth considered typical of Richardson’s designs, a central room with a stack for book storage on one side and a reading room on the other (as in Fairfield’s Lawrence Library).

An on-line writer described “quartered oak pillars and elaborate woodwork” in the “interior lobby and original stack room”; fireplaces on east and west walls; stained-glass windows with old printers’ marks and “scenes from Augusta history”; and in the reading room “frescoes, stained glass and gold leaf ornamentation.”

In Shettleworth’s vocabulary, the hall and stack room “are finished in dark Colonial Revival woodwork,” and “the reading room has a lavish white and gold French Renaissance décor.” He added that the upper story included a meeting room and storage space.

His final words as he recommended the library for National Register listing were: “The beauty of its exterior Romanesque Rival design combined with the richness of its interior have made it the most important library of the Richardsonian manner in Maine.”

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Shettleworth, Earle G., Jr., National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form, Lithgow Library, July 11, 1974.

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!