Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Railroad and trolleys

An early 19th century train.

by Mary Grow

Maine began building railroads in the 1840s. They did not replace stagecoaches, however, because the latter continued to connect railroad stops and stations to other population centers. The China history, for example, says that in the 1850s people wanting to go to China from the south or west could take the train to Augusta or Waterville and complete the journey by stagecoach.

According to Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, in 1836 Maine chartered the Portland and Kennebec railroad, and in 1845, two more railroads to serve the central Kennebec valley. The Androscoggin and Kennebec, the first to become operational, came to Waterville via Monmouth, Winthrop, Readfield and Belgrade. Ernest Marriner’s Kennebec Yesterdays includes a dramatic verbal picture of Waterville residents boarding the first Androscoggin and Kennebec train to visit the city on Nov. 27, 1849, and riding to Readfield to meet a train from Portland.

The group came back to Waterville on what he says is the first Portland-to-Waterville run. Their arrival was followed by a celebration that lasted into the evening, with cannon-fire, fireworks, a banquet, speeches (including one by U. S. Senator Wyman B. S. Moor, of Waterville) and a ball where the old-fashioned reel alternated with the newly-fashionable waltz.

The Penobscot and Kennebec, also chartered in 1845, was to leave Augusta and head northeast through Vassalboro and Winslow. In Waterville it was to connect with the Androscoggin and Kennebec and continue through Benton and Clinton to Bangor.

The Portland and Kennebec had not started building in 1845, but by 1849 it was heading up the Kennebec. On Aug. 27, 1850, Augusta voters agreed to lend $200,000 to help build “the railroad from Portland to Augusta,” Kingsbury wrote (without naming the railroad). The first locomotive came to Augusta Dec. 15, 1851. On Dec. 29, a crowd of thousands greeted the first complete train (Kingsbury does not specify a freight train, passenger train or combination); on Dec. 30 the first train to Portland left Augusta.

Reuben Wesley Dunn’s chapter in the Waterville centennial history, published in 1902, put the Androscoggin and Kennebec’s arrival in Waterville in December, rather than November, 1849. Soon afterward, he wrote, the company opened its first repair shop there.

The Androscoggin and Kennebec merged with the Penobscot and Kennebec, Dunn wrote (without giving a date) to form the earliest version of the Maine Central. This railroad absorbed others, including the Portland and Kennebec, and in the 1880s its leaders decided to consolidate Maine repair shops. They chose Waterville, and in 1887 opened what was then the best repair facility in the country. The brick buildings covered almost four acres and had electric lights. The shops generated power with two boilers, an engine and an air compressor. The 250 workers built and repaired both passenger and freight cars.

Hammond wrote in her history of Sidney that by 1850, the Androscoggin and Kennebec railway linked Portland and Augusta. In 1850, she wrote, a line was added to connect Augusta and Waterville. Although the center of Augusta and all of Waterville are on the west side of the Kennebec, the railroad ran through Vassalboro, necessitating two bridges across the river.

Hammond offers two theories for the detour: Sidney orchardists were afraid soot from train engines would harm their apple crop, or Sidney farmers wanted so much money for a right-of-way that the bridges were cheaper. However, Hammond prefers the explanation given by Alma Pierce Robbins in her Vassalboro history. Robbins wrote that Vassalboro mill owner John D. Lang used his national railroad connections to have the tracks laid on the east side of the Kennebec to serve his woolen mill in North Vassalboro.

The railroad, Robbins wrote, moved farm products to market and by 1900 gave farmers previously unheard-of security and prosperity. It transported people on business and for pleasure and, as tourism developed, brought in the summer people. It carried the mail. It provided good jobs, in terms of both pay and prestige.

The railroad turned out to have one drawback that Robbins thought worth mentioning: frequent trackside fires. In 1906, a fire destroyed most of the buildings at Getchell’s Corner, and a spark from a train was suspected as the cause, although Robbins said the case was never proved.

The Penobscot and Kennebec was extended to Fairfield in 1852. The town history records that on Jan, 24, 1854, leading businessman Henry C. Newhall sold land to the railroad (for $1,500) where what became the downtown – then Kendall’s Mills – railroad station was built. The railway line continued to Bangor the next year.

At some point a railway bridge was built across the Kennebec from Fairfield to Benton, because the Fairfield history says it burned in May 1861, was rebuilt and burned again in 1873. After that fire, the replacement bridge was built at Waterville and the main line rerouted through Benton, including Benton Station. A new steel bridge, built in 1917 and first crossed by a passenger train Jan. 13, 1918, put Fairfield back on the main line to Bangor.

In 1853, according to the Fairfield history, the Somerset and Kennebec (later the Somerset branch of the Maine Central) connected Augusta to Skowhegan via Kendall’s Mills. This line presumably served stations listed at Shawmut (then Somerset Mills), Nye’s Corner (then Fowler’s) and Hinckley (then Pishon’s Ferry). By 1988, the line ended at the Scott Paper Company plant.

Beginning in 1873, a separate railroad, the Somerset, passed through the western edge of Fairfield on its way from Oakland to Norridgewock and, by 1907, to Moosehead Lake. In 1988 it ran only as far as Anson.

The Maine Central tracks in 1892 crossed Benton diagonally, from Benton Station in the southwest (where the station was) to the middle of the northern boundary. The station was on a knoll where, according to Kingsbury, Dr. Ezekiel Brown was buried. He was a surgeon who served during the Revolutionary War and an early Benton settler; he died about 1820.

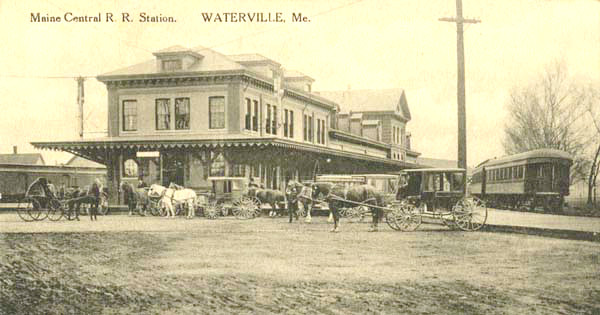

Each valley town and city had at least one railroad station, usually with long sheds for freight and a smaller area for passengers. Augusta’s was toward the south end of Water Street, a long brick building. Waterville’s was on the west side of College Avenue near the present underpass; a photo estimated to have been taken around 1900 shows a long wooden building with a three-story rectangular tower atop the passenger area. An undated on-line source lists 10 Maine Central stations in Fairfield; a photo elsewhere on line shows one, a small wooden building labeled Good Will Farm.

The Lewiston, Augusta and Waterville Street Railway had 153 miles of service trackage. Here, the trolley is crossing the bridge between Waterville and Winslow.

In some towns, street railways and trolleys competed with the locomotive-drawn long-distance railways. Local histories provide bits and pieces of information about central Kennebec Valley lines.

Kingsbury wrote that a street railway with horse-drawn cars started running between Waterville and Fairfield in 1888. In July 1892, as he was finishing his Kennebec County history, the Waterville and Fairfield Power and Light Company electrified the railway. It was the second electric railway in the county; the seven-mile Augusta Hallowell & Gardiner Electric Street Railroad Company had started in 1890.

Citing a talk by Philip Bowker, the Fairfield history says early in the 1900s, the corner of Main and Bridge streets in downtown Fairfield was the meeting place of three street railways, the Waterville, Fairfield and Oakland, the Benton and Fairfield and the Fairfield and Shawmut.

By 1894 the Waterville and Fairfield provided transportation to Island Park on Bunker Island (identified as Libbey Island on the current Google map). Amos Gerald, who founded the Electric Light Company in 1886 and five years later built a Mill Island generating station, created the park to promote business for the street railway, the history says.

Island Park had a bandstand and a roller-skating rink. Gerald built another rink at Emery Hill, north of downtown, that the history says was lighted and heated. Large groups could charter a separate trolley-car to get to his attractions.

(Gerald [1841-1913] was a Benton native who made a modest fortune as an inventor and became heavily involved in Maine electric railways. He and his wife, Caroline Rowell, had one daughter who married Maine author Holman Day, born in Vassalboro.)

Bowker said the trolley-cars had four wheels under the middle of the car. They ran on metal rails laid over wooden ties like the larger trains. Some cars were closed, with an entrance at the front; others were open, so that people could get on and off from the sides. He remembered crowded cars with passengers standing in the aisle and on the outside and rear platforms, which were intended as pathways for the conductor to collect fares. Despite such periods of discomfort, the trolley was popular for business and pleasure trips, he said.

A trolley-car was supposed to have a two-man crew, a conductor and a motorman. However, Bowker said, on the run to Shawmut there was often only a motorman. When a passenger got aboard an open car from the side, the motorman would let the train run by itself while he went back to collect the fare.

The Fairfield history mentions the Benton and Benton Falls Electric Railroad, started in December 1898 and extended to Fairfield in July 1899; and the Fairfield and Shawmut Railroad, started in 1906. The Benton line was owned by the United Boxboard and Paper Company, which used it to move pulp to its Benton Falls paper mill to be made into wrapping paper. During a sleet-storm about 1920, the history relates, a car loaded with heavy rolls of paper was parked on ice-coated tracks; it slid downhill, hitting a trolley-car and then the Benton end of the bridge, which sustained considerable damage.

The Waterville, Fairfield and Oakland line was the last in the area to be replaced by bus service, in 1937.

In Vassalboro, the Lewiston, Augusta and Waterville Street Railway bought a right of way over town property, location unspecified, in 1907, for $175, according to town report information compiled by Alma Pierce Robbins. Materials to build the railway were shipped over the Maine Central line; Italian laborers did much of the work.

The Kennebec Light and Heat Company put up poles along the electric car tracks in the Webber Pond area. The trolley’s motive power came from electricity carried through overhead wires. The still-standing brick power house at the end of Webber Pond was part of the electric railway.

The railway opened in 1909 and 1910 and, Robbins wrote, became competition for Maine Central. It also caused local changes; for example, Robbins wrote that elementary students who had been transported by road from the Pond Road to Riverside School instead took the cars to East Vassalboro School.

James Schad wrote in Bernhardt and Schad’s Vassalboro anthology that the first cars left East Vassalboro for Waterville at 6 a.m. and for Augusta at 7 a.m. daily. A trip from North Vassalboro to Waterville cost five cents in 1910.

When the trolley line began carrying coal to the woolen mill in North Vassalboro, Schad wrote, the coal trains ran at night, because “there was more power at night” and to avoid competing with passenger service.

In the winter, deep snow was a recurrent problem. Robbins describes residents along the line joining the motorman, conductor and passengers in shoveling drifts so the train could get through.

An on-line source says the railroad went into receivership in December 1918 and became part of a new Androscoggin and Kennebec Railway Company on Oct. 1, 1919.

The new company ran into an unusually severe winter, with over six feet of snow in one month and what the on-line writer calls “the storm of the century” in March 1920. Nonetheless, and despite increasing competition from automobiles, it remained profitable for a decade, partly because it did a good freight business.

In 1931, two bad things happened. The nation-wide Depression deepened, and the State of Maine decided to rebuild Route 201, which was very close to the rails as road and railroad left Augusta. Rather than incur the expense of moving track and overhead lines, the railroad quit: the last trolley-cars through Vassalboro ran on July 31, 1932. Schad wrote that the infrastructure was torn up soon afterwards.

Main sources

Bernhardt, Esther, and Vicki Schad, compilers/editors, Anthology of Vassalboro Tales (2017)

Fairfield Historical Society Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988)

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954)

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Web sites, miscellaneous

Next: The railroad that started in Wiscasset and never did get to Quebec, or even Farmington.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Enjoyed the article – and the photos. The first photo, by Marty Bernard, is NOT a “19th century train” – the caption is off by 100 years ! Note the electric headlight, the large boiler, and the large, heavyweight standard passenger cars – more likely, the 1940’s. Thanks for this history-filled item !

hay you should do the recent trolley tracks they found here in auburn