TECH TALK: Bug hunting in the late 20th century

(image credit: XDanielx – public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

ERIC’S TECH TALK

ERIC’S TECH TALK

by Eric W. Austin

Computer Technical Advisor

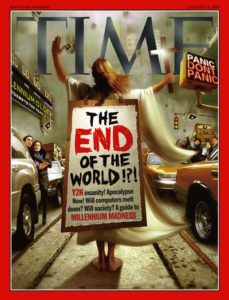

The year is 1998. As the century teeters on the edge of a new millennium, no one can stop talking about Monica Lewinsky’s dress. September 11, 2001, is still a long ways off, and the buzz in the tech bubble is all about the Y2K bug.

I was living in California at the time, and one of my first projects, in a burgeoning technical career, was working on this turn of the century technical issue. Impacting the financial sector especially hard, which depends upon highly accurate transactional data, the Y2K bug forced many companies to put together whole departments whose only responsibility was to deal with it.

I joined a team of about 80 people as a data analyst, working directly with the team leader to aggregate data on the progress of the project for the vice president of the department.

Born out of a combination of the memory constraints of early computers in the 1960s and a lack of foresight, the Y2K bug was sending companies into a panic by 1998.

In the last decade, we’ve become spoiled by the easy availability of data storage. Today, we have flash drives that store gigabytes of data and can fit in our pocket, but in the early days of computing data-storage was expensive, requiring huge server rooms with 24-hour temperature control. Programmers developed a number of tricks to compensate. Shaving off even a couple of bytes from a data record could mean the difference between a productive program and a crashing catastrophe. One of the ways they did this was by storing dates using only six digits – 11/09/17. Dropping the first two digits of the year from hundreds of millions of records meant significant savings in expensive data-storage.

This convention was widespread throughout the industry. It was hard-coded into programs, assumed in calculations, and stored in databases. Everything had to be changed. The goal of our team was to identify every instance where a two-digit year was used, in any application, query or table, and change it to use a four-digit year instead. This was more complicated than it sounds, as many programs and tables had interdependencies with other programs and tables, and all these relationships had to be identified first, before changes could be made. Countrywide Financial, the company that hired me, was founded in 1969 and had about 7,000 employees in 1998. We had 30 years of legacy code that had to be examined line by line, tested and then put back into production without breaking any other functionality. It was an excruciating process.

It was such a colossal project there weren’t enough skilled American workers to complete the task in time, so companies reached outside the U.S. for talent. About 90 percent of our team was from India, sponsored on a special H-1B visa program expanded by President Bill Clinton in October of ’98, specifically to aid companies in finding enough skilled labor to combat the Y2K bug.

For a kid raised in rural New England, this was quite the culture shock, but I found it fascinating. The Indians spoke excellent English, although for most of them Hindi was their first language, and they were happy to answer my many questions about Indian culture.

I immediately became good friends with my cube-mate, an affable young Indian man and one of the team leaders. On my first day, he told me excitedly about being recently married to a woman selected by his parents while he had been working here in America. He laughed at my shock after explaining he had spoken with his bride only once – by telephone – before the wedding.

About a month into my contract, my new friend invited me to share dinner with him and his family. I was excited for my first experience of true Indian home-cooking.

By and large, Californians aren’t the most sociable neighbors. Maybe it’s all that time stuck in traffic, but it’s not uncommon to live in an apartment for years and never learn the name of the person across the hall. Not so in Srini’s complex!

Srini lived with a number of other Indian men and their families, also employed by Countrywide, in a small apartment complex in Simi Valley, about 20 minutes down the Ronald Reagan Freeway from where I lived in Chatsworth, on the northwest side of Los Angeles County.

I arrived in my best pressed shirt, and found that dinner was a multi-family affair. At least a dozen other people, from other Indian families living in nearby apartments – men, women, and children – gathered in my friend’s tiny living room.

The men lounged on the couches and chairs, crowded around the small television, while the women toiled in the kitchen, gossiping in Hindi and filling the tiny apartment with the smells of curry and freshly baking bread.

At dinner, I was surprised to find that only men were allowed to sit around the table. Although they had just spent the past two hours preparing the meal, the women sat demurely in chairs placed against the walls of the kitchen. When I offered to make room for them, Srini politely told me they would eat later.

I looked in vain for a fork or a spoon, but there were no utensils. Instead, everyone ate with their fingers. Food was scooped up with a thick, flatbread called Chapati. Everything was delicious.

Full of curry, flatbread, and perhaps a bit too much Indian beer, Srini and his wife walked me back to my car after dinner. Unfortunately, when Srini’s wife gave me a slight bow of farewell, a tad too eager to demonstrate my cultural savoir-faire, I mistook her bow for a French la bise instead. Bumped foreheads and much furious blushing resulted. Later, I had to apologize to Srini for attempting to kiss his wife. He thought it was hilarious.

Countrywide survived the Y2K bug, although the company helped bring down the economy a decade later. Srini moved on to other projects within the company, as did I. The apocalypticists would have to wait until 2012 to predict the end of the world again, but the problems – and opportunities – created by technology have only grown in the last 17 years: driverless cars, Big Data, and renegade A.I. – to deal with these problems, and to exploit the opportunities they open up for us, it will take a concerted effort from the brightest minds on the planet.

Thankfully, they’re already working on it.

Here at Tech Talk we take a look at the most interesting – and beguiling – issues in technology today. Eric can be reached at ericwaustin@gmail.com, and don’t forget to check out previous issues of the paper online at townline.org.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!