The Abel Jones House. (photo by Roberta Barnes)

Old houses/buildings can appear to be of no interest other than to be torn down and replaced with modern structures.

When you take a moment and think of old buildings in need of more than a coat of paint the building can look quite different. These old buildings, such as the Jones house on the Jones Road, in China, Maine, are part of the journey that led to today’s communities, states, and our country.

The craftsmanship put into not just the interior woodwork, but such things as an organ. (photo by Roberta Barnes)

If the owners allow you to look inside of old buildings, you can see the hand-made beauty that is a reminder of our past. The historical appreciation of the craftsmanship that went into the building of these old houses and even the small wood stoves and fireplaces that heated each room are treasures that go beyond monetary value.

This summer on Saturday, August 26, Jen Jones, a China Historical Society member, offered a brief tour of her newly-acquired Rufus Jones homestead. The tour included a few downstairs rooms inside the Jones House built by Abel Jones in 1815. Jen and her younger brother were on site to talk with those on the tour and answer questions about their ancestral home where they, children, and grandchildren will occasionally stay throughout the year.

The tour began inside the new China library still under construction. History of the Jones family was given by speakers’ Quaker historian Joann Austin, South China Library head Jean Dempster, and Jen Jones great-great-granddaughter. Outside in the library’s parking lot on our way to tour inside the Jones house, a side of the house not seen in most photographs, is visible. From this distance it looks as it will once the restoration has been completed.

Many stories were told about the Jones ancestors. One of the stories told was of a horse being attached/hitched to the sleigh and then going across China Lake to visit people on the other side. All those stories showed the long journey that led the Abel Jones homestead to no longer being seen as an old house, but one of historical value.

In the small dining room, hanging over the mantle of the fireplace, is a painting of the husband and wife of the early owners. (photo by Roberta Barnes)

Once at the Jones house, walking through the small rooms transformed an old rundown house into treasures of the past. The craftsmanship put into not just the interior woodwork, but such things as an organ, cast iron wood stove, sofa and highly-polished pumpkin pine wide floorboards made the outside peeling paint and slanted floors unimportant.

Entering through the back door of what looked to be part of the barn attached to the house, many old tools were visible. From there a small kitchen was dominated by a multifunction red brick wood stove; an old model electrical stove suggested that it had not been used for years. Cupboards seen in today’s kitchens were absent. However, a large cupboard door covering multiple shelves and a butler’s pantry, common in the past, erased the need for today’s cupboards.

In the small dining room, hanging over the mantle of the fireplace, is a painting of the husband and wife of the early owners. To the right is a framed hand-drawn map that is another reminder of past treasures.

While the peeling paint and slanting floors might not rate high on a realtor’s appraisal value, the historical value of the Jones house is another story. The two ladder-back chairs stopping visitors from going upstairs because of unsafe floors were examples of furniture beginning in the mid-17th century.

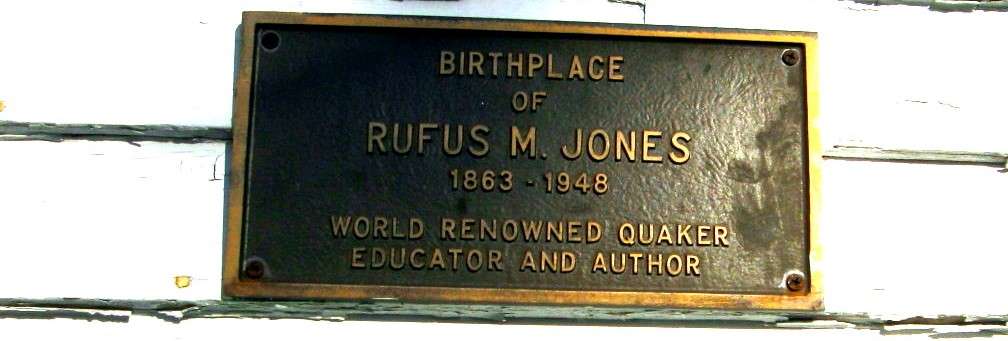

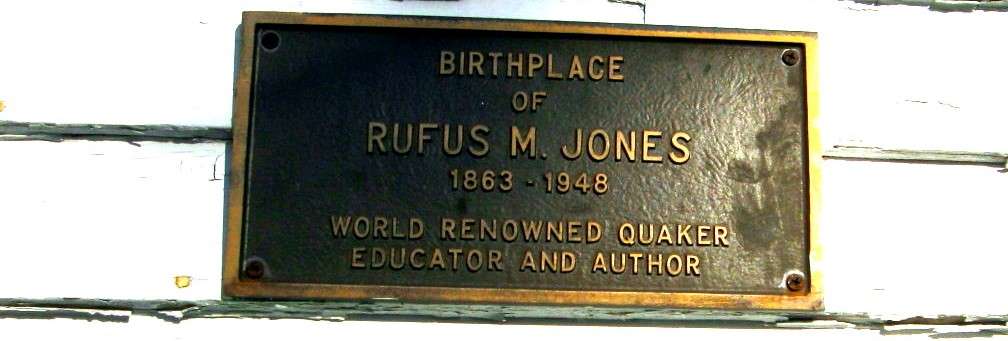

Outside on the side of the house facing the street is the metal plaque designating the Jones house as the birthplace of Rufus M. Jones. Many people associate the house with the important Quaker writer and historian Rufus Matthew Jones 1, as this was his birthplace and childhood home. His history and accomplishments are extensive.

This Jones house on the side of China Rd., built in 1815 by Abel Jones, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1983 by Gregory K. Clancey Architectural Historian of the Me Historic Preservation Comm.

Clancey writes that at that time in 1983 the Jones House is still owned by members of the Jones family. In The Town Line article written by Mary Grow in July 2021, she states that “The South China Library Association is the present owner.” Nevertheless, today the Jones house owners are members of the Jones family, ancestors of Abel Jones the original owner.

In Clancey’s application to have the Jones house put on the national registry he described some of the house in this way. “The Jones homestead is a typical Maine Federal farmhouse – two-and-one-half stories with pitched roof, five bays long, two bays deep, with a long one-and-one-half story ell projecting from the rear wall. The main section is perpendicular to the road. Sometime in the late 19th century the house was re-oriented toward the dooryard and road. The new door was given a simple Queen Anne canopy. All rooms are very simply decorated, with wallpaper applied over plaster. A few rooms retain simple Federal mantlepieces. One of the mantels is an exact copy of the original, which was somehow destroyed. A large barn and small shed of late 19th – early 20th century construction stand behind and to one side of the ell.”

If you were not able to attend the tour, you can find some of the Jones family history in books and copies of old newspapers at those places of recorded stored knowledge we call libraries. Some history can also be found online. Jen Jones suggested such resources as Wikipedia – the Abel Jones House, china.goveoffice.com, The Town Line articles such the 1997 South China Inn Community, and books such as Friend of Life – Biography of Rufus M. Jones and A Small Town Boy, by Rufus M. Jones.

To the editor:

To the editor: