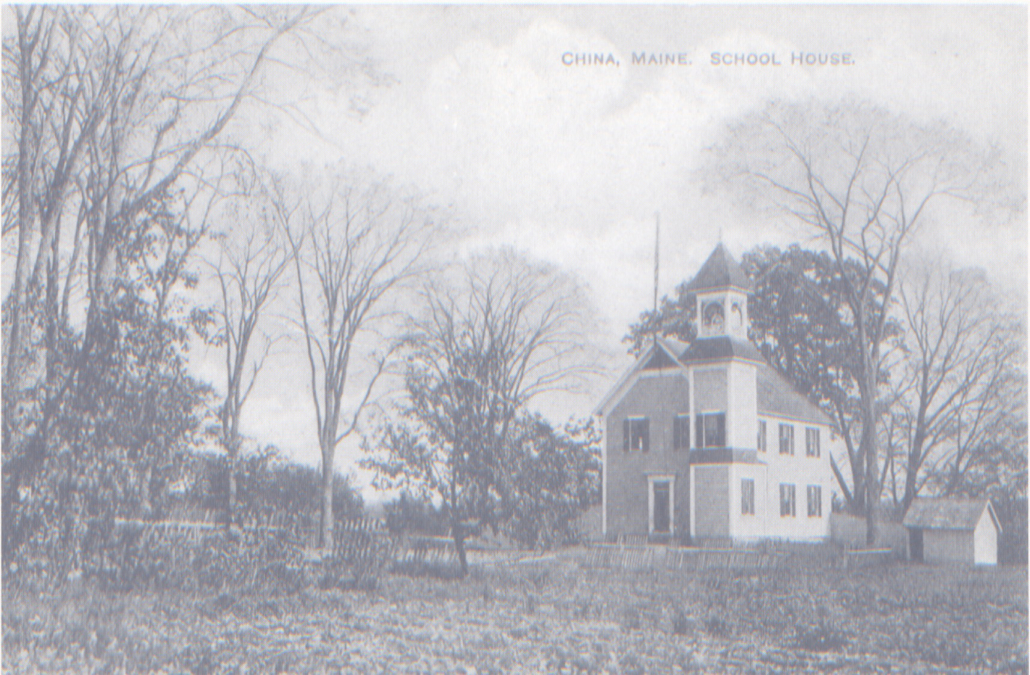

PAGES IN TIME: Remembering China Village’s two-room schoolhouse

China Village two-room schoolhouse, 1888-1949. It was located across from the Albert Church Brown Memorial Library. (photo courtesy of David Fletcher)

by Richard Dillenbeck

I attended grammar school in a two-room schoolhouse in the village of China at the northern end of the lake. It had two rooms, each with four grades, the younger kids on the ground floor and the older children on the second, each room with its own teacher.

The rooms were arranged by rows of desks, each row having children in the same grade, and each row a different grade. The teacher would move from row to row while keeping an eagle eye on the other rows. In the rear left corner, there was a large wood-burning stove, the only heat source in winter; a bank of single pane windows on the right side of the room admitted light to the whole room, supplementing the bare light bulbs on the ceiling. The teacher’s desk was at the front, with a large blackboard behind it with the United States’ flag in one corner. Every morning, we children stood and recited the Pledge of Allegiance, to which “under God” had not yet been added. (Those two words were added in 1954 during a time when we were locked in a cold war with the Soviet Union and we wanted “them atheistic Russkis” to know we were a God-fearing nation.) In winter, the older boys would go down the back stairs and bring up a large “junk” (Mainer-speak) of wood to fill the fuel box.

Photo of students at China Village Schoolhouse sometime in the mid-1930s. (Contributed by Robin Adams Sabattus.) Picture includes: Carolyn James, Paul Boivin, Frances Black, Paul Fletcher, Muriel Harding, Richard Starkey, John McKiel and Donald Black.

On the first floor, attached to the school’s northern side, was a divided girl/boy outhouse with a built-in plank with three holes for the girls and a three-holed plank for the boys. In the dead of winter, no one enjoyed sitting there when the icy wind blew up through the hole, but when we had to go, we would raise two fingers and the teacher would either nod to us or signal for us to wait. (One raised finger meant we needed to use the pencil sharpener installed at the front of the room.) I don’t know how she did it, but Mrs. Stewart handled it all with aplomb and kept us in our places. We wouldn’t think of misbehaving.

That is until one day there suddenly was a loud commotion in the rear corner of the room and all heads shot up and turned in time to see Mrs. Stewart slam one of the biggest boys in the room up against the stove. She admonished him to, “Sit down and don’t do it again!” He meekly went back to his desk and sat down, and we didn’t hear a peep out of him for the rest of the school year. We never knew what he had said or done, but we sure knew how Mrs. Stewart, who probably weighed no more than 110 pounds, handled it. Our respect for her soared even higher.

The school day included a daily recess when we all had to go outside. Dodge ball and hide and seek were popular. Most of us, except the kids who lived in China village and walked to school, were transported by buses and everyone brought a lunch box. It was always fun to compare lunches with what others brought and to sometimes trade. My favorite sandwiches, a different kind made by my mother every morning, were either a baked bean sandwich or a Spam sandwich with lettuce and ketchup. It always seemed a long time since the small bottle of milk we received mid-morning.

At some point in the seventh grade, we started getting hot soup for lunch, at least those who paid for it did. It was made down the village street by a woman at her home, and two of the bigger boys would be sent to her house to bring back a bucket of soup between them.

Once a week, we were allowed to go to the China library, which was directly across the street. I got hooked on the Tarzan books and read every one in the library, enjoying the description of the jungle, Tarzan’s animal friends and enemies, and his exciting adventures. I can still recall how thrilling it was to later see Tarzan come to life in movies starring Johnny Weissmuller, the former Olympian swimmer, who portrayed Tarzan in the movies for many years, even long after he had aged and lost his svelte shape. His jungle-call in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ novels could carry for miles through the jungle and was used when he needed to exult about some kill or to summon help from his animal friends. Each movie managed to put that jungle call in every movie more than once. I was amused to hear it recently on the internet – just look up “Tarzan yell.”

In 1948, we learned a new combined community school would be built for the Town of China, halfway between the villages of China and South China. Construction of the first classrooms was completed by the spring of 1949. We were all excited and perhaps a bit anxious because attending a bigger school with kids we didn’t know led to much discussion. Mrs. Stewart gracefully handled it by letting us ask questions and verbalize our feelings, and she assured us the new school would be much nicer and would have real bathrooms – with running water, real toilets and a real furnace for heat. The school in China Village was converted to rearing chickens rather than children and then it burned down. (No one seems to know how the chickens fared.)

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!