REVIEW POTPOURRI: The Bronte sisters poetry

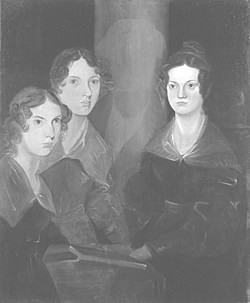

Anne, Emily, and Charlotte Brontë, by their brother Branwell (c. 1834). He painted himself among his sisters, but later removed his image so as not to clutter the picture. (National Portrait Gallery, London.)

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

In 1846, a slim volume, Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, was published in Great Britain, sold two copies and generated three unsigned, but very positive reviews. Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell were, due to the damn-with-faint-praise prejudice against women writers, pseudonyms for Charlotte (1816-1855), Emily (1818-1848), and Anne (1820-1849) Bronte. Since the sisters were little girls, they were writing poems, romances and stories as games of the imagination.

The Brontes were three of six children born to the Reverend Patrick (1777-1861) and Maria (1783-1821) Bronte. From all accounts, the parents were very kind, committed to education and provided material needs. But the family was cursed by tragedy and sorrow. The oldest daughters Maria and Elizabeth died in their teens, the mother perished from tuberculosis when Emily, the youngest, was only three and the remaining three girls and one son passed away within a seven-year period, with the father outliving all of them.

Emily is arguably considered the most gifted of the three sisters as a poet and contributed 21 poems to the volume; a book of her collected poems would number over 200.

The usual adjectives of powerful, eloquent, beautiful, sublime seem like very tired cliches when describing their effect. Her passionate, solitary nature lent the several ones I have read a complex range of emotions (the fascination with the wild, windy English moors and rocky cliffs in her novel Wuthering Heights strengthen her poetic imagery) and, even more importantly, universal wisdom of a spiritual nature.

One of the unsigned reviews praised her poems for a “fine, quaint spirit” and that they had “things to speak that men will be glad to hear, – AND an evident power of wing that may reach heights not here attempted.”

I offer The Old Stoic:

“Riches I hold in light esteem,

And Love I laugh to scorn;

And lust of fame was but a dream

That vanished with the morn;

And if I pray, the only prayer

That moves my lips for me

Is, ‘Leave the heart that now I bear,

And give me liberty!’

Yes, as my swift days near their goal,

‘Tis all that I implore:

In life and death a chainless soul,

With courage to endure.”

This poem conveyed Emily’s scorn of materialism, ‘Riches in light esteem’; her disdain for ordinary notions of romance, ‘Love I laugh to scorn’ – she was the consummate introvert and allowed very few people to get close to her, except her sister Anne, but she was compassionate towards the less fortunate; and a fearless search for righteousness and spiritual victory – ‘In life and death a chainless soul, /with courage to endure.’

One of Emily’s teachers wrote the following:

“She should have been a man – a great navigator. Her powerful reason would have deduced new spheres of discovery from the knowledge of the old; and her strong imperious will would never have been daunted by opposition or difficulty, never would have given way but with life. She had a head for logic, and a capability of argument unusual in a man and rarer indeed in a woman…. impairing this gift was her stubborn tenacity of will which rendered her obtuse to all reasoning where her own wishes, or her own sense of right, was concerned.”

Her sense of right and of tender compassion are interestingly juxtaposed in the following anecdote. When she was six, her brother Branwell had been naughty and their father asked how he should deal with the little guy. She replied, “Reason with him, and when he won’t listen to reason, whip him!”

Emily Bronte came down with a cold while attending her brother’s funeral in September 1848, which developed into tuberculosis, but she refused all medical help until the very end when it was too late, being determined that no doctor would poison her. She died within three months on December 19, at 2 p.m., with older sister Charlotte tending her.

To conclude, one of Emily’s untitled poems:

“All hushed and still within the house;

Without – all winds and driving rain;

But something whispers to my mind,

Through rain and through the wailing wind,

Never again.

Never again? Why never again?

Memory has power as real as thine.”

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!