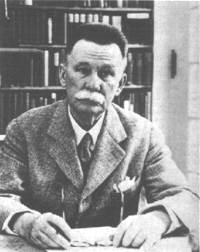

REVIEW POTPOURRI: Van Wyck Brooks

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Van Wyck Brooks

In his fascinating 1936 literary history, The Flowering of New England, Van Wyck Brooks (1886-1963) astutely commented on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in an essay, justifying the importance of a poet’s profession, its nobility and necessity to life itself:

“Poetry did not enervate the mind or unfit the mind for the practical duties of life. He hoped that poets would rise to convince the nation that, properly understood, ‘utility’ embraces whatever contributes to make men happy. What had retarded American poetry? What but the want of exclusive cultivation? American poetry had been a pastime, beguiling the idle moments of merchants and lawyers. American scholarship had existed solely to satisfy the interests of theology.

“Neither had been a self-sufficient cause for self-devotion. Henceforth, let it be understood that he who, in the solitude of his chamber, quickened the inner life of his countrymen, lived not for himself or lived in vain. The hour had struck for poets. Let them be more national and more natural, but only national as they were natural. Eschew the skylark and the nightingale, birds that Audobon had never found. A national literature ought to be built, as the robin builds its nest, out of the twigs and straws of one’s native meadows. “

Between 1620, when the Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth, Massachusetts, and 1815, when the creative spirits were gaining firmer ground in New England, the country was fighting for survival in an untamed wilderness. Farming and the formation of a civil society under the eyes of a just, loving and wrathful God were facts of life. Art, music and literature were mostly frowned upon except during the few patches of free time.

But a few worthwhile poets did emerge – the Puritan Anne Bradstreet (1612-1672, who married her husband Simon when she was 16); the physician and pastor Edward Taylor (1642-1729, who moved to the remote settlement of Westfield, Massachusetts, in the Berkshires and wrote some very intricate verses during his spare time that were discovered 200 years after his death in the back rooms of the Yale University Library) and William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878, whose family was originally from Knox before settling in Massachusetts).

However, the Romantic period in England and Europe brought about a passionate, very subjective individuality that would inspire Longfellow, his friend Hawthorne and Emerson, Thoreau and other Transcendentalists.

For what it’s worth, English poets were writing Odes and other tributes to nightingales while Longfellow did celebrate the beauties of nature frequently and not just the twigs. I look out on the back lawn in November and see a lot of twigs and stripped branches but do look forward to the end of winter in late May.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!