Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Albion schools

by Mary Grow

Note: some of the following information was previously published in The Town Line on September 30, 2021.

The Town of Albion, north of China and east of Winslow, had half a dozen European families by 1790, according to Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history. The area, including until 1818 the north end of present-day China, was organized as Freetown Plantation in 1802.

On March 9, 1804, the Massachusetts legislature incorporated it as the Town of Fairfax. Fairfax became Lygonia (or Lagonia) on March 10, 1821, and Albion on Feb. 25, 1824.

Ruby Crosby Wiggin wrote in her 1964 Albion history that the first plantation meeting was held at 10 a.m. Saturday, Oct. 30, 1802. Voters chose major local officials.

At a second meeting, on Monday, March 8, 1803, there were more elections and the first appropriations. Voters authorized spending $50 for “plantation charges”; paying the three assessors $1 per day; and paying the meeting moderator $1.

There were more meetings in April and October 1803 and March 1804. Wiggin found the first reference to education at the April 16, 1804, meeting (after Freetown Plantation became the Town of Fairfax): voters approved $200 “for schooling” (and $1,200 for roads, payable in money or equivalent).

At an Aug. 25, 1804, meeting, Wiggin wrote, voters created five school districts; elected a three-man committee to run each district; and elected “a committee for the purpose of building schoolhouses.”

School money was allocated according to the number of “scholars,” defined as residents between three and 21 years old, in each district. District committees hired teachers and oversaw building maintenance; students provided their own textbooks.

As in other Kennebec Valley towns, early school districts were described by town lines and lot lines. The description Wiggin quoted for District 1, for example, said it covered the area “from the north line of H. Miller’s to N. Wiggin’s at the town line, then east to the eastern line of the Williams lot, then running [is a direction omitted here?] until it intersects the Heywood lot.”

District 1 was in southwestern Albion; two of its first three committeemen were Nathaniel Wiggin and Japheth Washburn, settlers in China in 1803 and 1804. Ruby Crosby Wiggin commented on how District 1 appeared and disappeared in town records.

She found that much of its territory, maybe including the schoolhouse, became part of China in 1818. In November 1821, Albion’s District 1 reappeared, with 24 students. On Oct. 25, 1823, voters abolished it, though 31 students were listed. It reappeared in 1838, and was listed until 1846, when it apparently was permanently eliminated.

Voters approved seven districts in March, 1805, and nine, with a total of 316 students, in May, 1805, Wiggin said.

She did not record how many schoolhouses were built, but apparently not enough. Voters in 1809 approved taxing non-residents, defined as “Winthrop and Lloyd, Nathan Winslow and the Plymouth Company,” specifically to raise money to build schoolhouses.

(The Plymouth Company, the Boston-based group also called Kennebec Proprietors and other names as it changed corporate structure, hired Falmouth surveyor Nathan Winslow to lay out lots on several of its Kennebec Valley tracts; Kingsbury said Winslow was assigned land in Fairfax. Wiggin wrote that in 1809 the company still owned 9,498 acres in Fairfax. Your writer could not identify Winthrop and Lloyd.)

In 1814, Wiggin wrote, voters created a tenth school district.

By 1816, she said, town meetings were being held in the District 7 schoolhouse (which she was unable to locate precisely), while voters argued about building a town house. The town house finally came into use in late 1817 or early 1818, also in District 7. But, Wiggin wrote, a January, 1823, town meeting was in the District 7 schoolhouse.

(The 1856 map of Albion in the Kennebec County atlas shows a town house south of Albion Corner [approximately the current business district on Route 202], on a road running west from the stream crossing formerly called Puddledock.)

From 1830 to 1842, Wiggin found, voters approved about $500 a year for schools. In 1843 they raised the amount to $686 annually, and kept it there for a decade.

The 1856 atlas shows 10 Albion schoolhouses. Three were in the southern part of town. One of the southern schoolhouses was named first Shaw and later Davis, Wiggin said, giving no dates. It was near a store run by a man named Shaw, a blacksmith shop and an inn.

The 1879 Albion map shows C. H. Shaw’s house and a blacksmith shop between South Albion and the Quaker Hill Road schoolhouse in eastern Albion.

Another schoolhouse was on South Freedom Road, near Puddledock (called in the 1879 atlas South Albion).

Two western schoolhouses were on Back Pond Road (aka Clark Road), west of Lovejoy Pond. (The southern of these, Wiggin said, had become District 1 by 1858.) Three more were in northern Albion.

The schoolhouse closest to present-day downtown Albion was a little south of the business area, on the west side of what looks like present-day Route 202, almost due east of the northern tip of Lovejoy Pond.

Wiggin gave interesting details about some of Albion’s district schools, but unfortunately she located them mostly by reference to 1960s property-owners. For example, she quoted a resident whose father said District 4, at some point, had a brick schoolhouse with a clock on the outside whose hands pointed permanently to 8:45.

She did locate one controversial school building: in the 1860s, she said voters argued for six years over replacing the District 8 schoolhouse, with the dispute including a lawsuit. In 1868 a new schoolhouse went up on the Main Street lot where the Besse building, home of the town office, now stands.

Ernest C. Marriner, in his Kennebec Yesterdays, dipped into the report of Albion’s school committee for 1861. (The 1861 date might mean the report was published in the spring of 1861 and covered the previous year, since early 1860; or the report was for the year 1861.)

Marriner said the committee found that schools were “flourishing,” in spite of a diphtheria epidemic that killed 17 students (in 1860 or 1861, presumably). But Wiggin quoted from a town report saying 17 students died of diphtheria “during the school year of 1862-3.”

Marriner and Wiggin agreed that Albion had 14 school districts in 1861 – Wiggin listed them by number and name, not by location. By then a single agent was in charge of each district, with the town committee (Marriner) or town school supervisor (Wiggin) overseeing all.

The report Marriner cited criticized individual teachers who failed to maintain discipline, and singled out the District 5 (Quaker Hill, per Wiggin) schoolhouse that was poorly maintained.

Limited success in District 3 – the Crosby Neighborhood school, in southeastern Albion, Wiggin said – was not the teacher’s fault. Marriner quoted: “with so much ice, the fondness for skating rather than for school, and the parents seemingly willing to have it thus, the term was not very profitable.”

By 1862, Wiggin said, “all legal residents” of each district could participate in district meetings at which they voted on “the upkeep of the school property, board of the teacher, wood [firewood for heating] and other matters pertaining to the school.” The district school agent apparently hired the teacher.

In 1879, Wiggin reported, Albion’s summer schools cost $343.61, with the average term eight weeks plus four to six days. Winter schools cost $738.65, and the average term was 11 weeks plus one to three days. She did not say whether all 14 schools operated both terms.

Women teachers were paid, on average, $3.15 a week; men earned, on average, $28 a month.

In March, 1890, Wiggin wrote, there were 323 students, and voters appropriated $951 for “school expenses.” (By this time, the State of Maine also supported schools, so the total school budget was higher.)

Kingsbury said by 1892 a decreasing population led officials to cut the number of districts to 11, serving about 250 students. The town was providing uniform textbooks, and “school property is valued at about $3,000, and is kept in good repair,” he wrote.

Wiggin wrote that the town report for April 1893 to March 1894 said District 6 had been eliminated. By 1896, she said, Albion had so few students that five district schools had been closed, with their students “sent to other schools.”

The first mention of “conveying scholars” Wiggin found in the school report for 1897. Half a dozen men were paid from $1 to $3 per week. Her book includes an undated photograph labeled “Albion’s first ‘school bus,’ horse drawn,” showing a group of students and a boxy vehicle in front of the Besse Building (built in 1913).

* * * * * *

Wiggin wrote that “subscription high schools” were taught in Albion in 1860. One shared the District 3 schoolhouse in southern Albion.

In April 1873, she said, a group of residents organized a stock company to provide a public high school. Group leaders quickly sold 90 shares, at $10 a share, and appointed a three-man building committee.

Wiggin said Albion’s first free high school opened in 1874 or 1875; Kingsbury said 1876. After “several years” (Kingsbury), or around 1880 (Wiggin), voters stopped appropriating money for it, Wiggin said due to lack of interest. In 1881, the trustees began the process of conveying the building to the local Grange; by 1892, it was the Grange Hall.

The free high school reopened, either in 1884 (Kingsbury) or about 10 years after it was closed (Wiggin). Wiggin wrote that into the 1890s, fall terms – 10 weeks in 1891 – met in District 8, in the Albion Village schoolhouse, and spring terms – in 1892 also 10 weeks – met in District 9, in the McDonald schoolhouse.

The fall term had 87 students and cost $214, the spring term 33 students at a cost of $82. The state and town split the cost, $147 each, she wrote.

Kingsbury again offered slightly different information. As of 1892, he wrote, the fall high school term was held in the Number 10 schoolhouse in the Shorey District, and the spring term in the Number 8 schoolhouse in the village.

He wrote that the high school “has since [it reopened] received cordial support.” This support waned, Wiggin wrote, “until in 1898 the average attendance at the village was only 18, and the high school at McDonald was discontinued entirely.”

The “village school” was apparently the 1868 one on Main Street, where the Besse Building now stands. It was revived as a high school after 1898 and served until 1913, with the roof raised twice to accommodate more classrooms.

Wiggin wrote, “From this school came the first pupil to graduate from Albion High School with a diploma.” His name was Dwight Chalmers, his graduation year 1909.

Wiggin said the old high school building was moved to a new site and in 1964 was a private home.

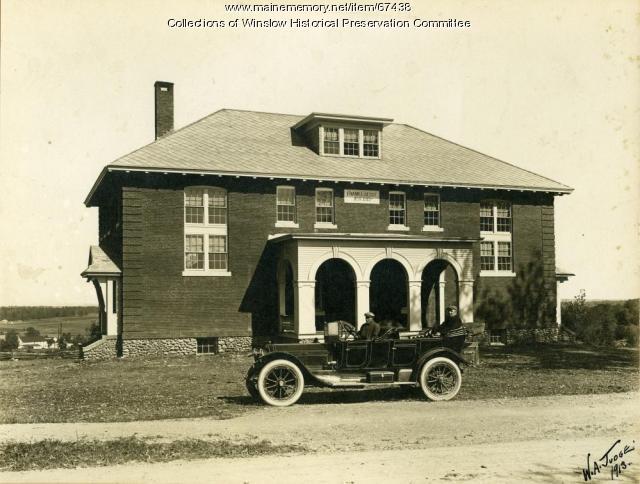

The Besse Building was a gift of Albion native, later Clinton resident, Frank Leslie Besse. Designed by Miller and Mayo, of Portland, and built by Horace Purington, of Waterville, it was dedicated as Besse High School on Sept. 20, 1913.

* * * * * *

Benton, Clinton and Fairfield combined as Maine School Administrative District (MSAD) #49, now Regional School Unit (RSU) #49, in January 1966. Albion joined in September of the same year. In 2025, Fairfield’s Lawrence High School serves all four towns.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954).

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!