Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Education in Winslow & Waterville

by Mary Grow

The northernmost of three area towns incorporated on April 26, 1771, was Winslow, on the east bank of the Kennebec River, then including Waterville and Oakland on the west bank.

As discussed in earlier articles, Teconnet or Ticonic, later Winslow, was one of the earliest European-settled areas on this part of the river, with a British trading post in the 1650s and a British fort in 1754. Henry Kingsbury wrote in his Kennebec County history that Winslow’s first town meeting was held Thursday, May 23, 1771.

Your writer has found little information on 18th century schooling in Winslow and less on the 19th century. Elwood T. Wyman, in his chapter on education in Whittemore’s 1902 history of Waterville, commented that early residents on the Winslow side of the Kennebec could not always afford an education appropriation.

In 1778, town meeting voters agreed to pay a preacher but not a teacher, he said. In 1780, 1788, 1789 and 1790, they funded neither.

In 1791, they appropriated 50 pounds for schooling and nothing for preaching. In March 1796, voters – still representing both sides of the river – approved $250 for education, by now switching to dollars.

Wyman wrote that in addition to the struggling public schools, some wealthier residents supported private schools. He gave as an example a Dec. 28, 1796, agreement (signed Feb. 7, 1797) between nine residents (from both sides of the river) and Abijah Smith (later Waterville’s town clerk) for Smith to run a school in Ticonic Village (on the Winslow side) for three months.

Smith was to find his own room and board and a schoolroom (whether the living and teaching quarters were separate is unspecified). He was to be paid a total of $60, $2 a month for board and the remainder at the end of the term; and his sponsors would deliver firewood for the school.

Wyman switched his focus from Winslow to Waterville in 1802, when the two towns separated. Kingsbury provided no historical details on education in the Winslow chapter in his history. Again (as with Sidney), he described Winslow education only in 1892, the year his book was published.

Notes by Winslow historian Jack Nivison on the Winslow Historical Society’s website describe two 19th-century school buildings depicted there: the 1819 Fort School on the west side of Lithgow Street, near the Kennebec; and the 1887-88 Sand Hill School, at the corner of Monument and Bellevue streets, well uphill from the river.

The original Fort school was one room. Nivison said it might have been Winslow’s earliest public – he emphasized “public” – school.

An on-line site says it was used until 1909, when increasing enrollment required the new, larger Fort School, built in 1910. This two-room Fort School was on the east side of Lithgow Street, three lots south of the first one.

The original Fort School was reused for a year or two after a high school burned down in 1914, the on-line site says. In 1976, the building became the Winslow Historical Society’s museum. It was destroyed in the Flood of 1987.

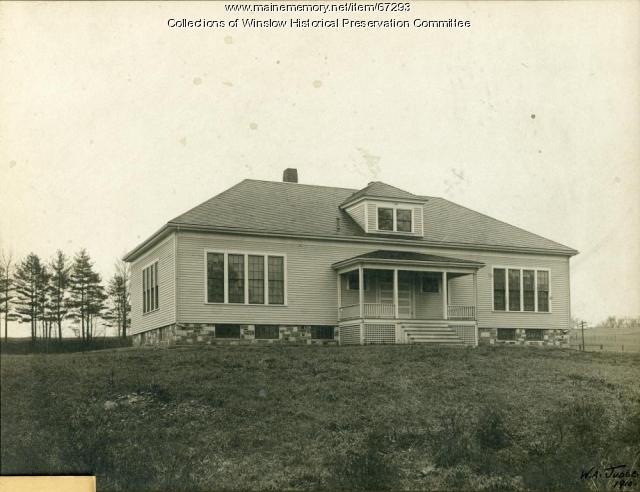

The Sand Hill School was the largest in town when it was built, Nivison wrote. The accompanying photograph, taken after a 1909 addition, shows a tall, two-story, L-shaped building. Sand Hill School was “always an elementary school,” though with “different grades at different times.” It closed after the 1929-30 school year.

Kingsbury, describing Winslow education in 1891-92, said there were 16 school districts, 15 schoolhouses “and eleven schools that were taught in 1892,” attended by 247 students.

Funding, he summarized, consisted of $1,400 “in public money” (state funds?), $1,500 from town taxes and another $250 “for the support of free high schools.”

* * * * * *

In the 1902 Waterville history, Wyman summarized education-related actions at early town meetings after Waterville was incorporated as a separate town on June 23, 1802.

At the first meeting on July 26, voters elected 10 men as school agents. At an Aug. 9 meeting, they raised $300 for education. In March, 1803, they approved another $400; and on May 2, 1803, they accepted a report from the selectmen establishing 10 school districts.

Eight districts were named after residents; the “village district,” No. 1, was Ticonic and the third was Ten-lot. Names had changed to numbers by around 1808. But, Wyman said, in 1902 some districts’ residents were still using the family names.

The selectmen also recommended, and voters approved, having annual town meeting voters choose school agents and letting each district’s residents contract with their teachers, within legal limits. Selectmen were authorized to aid small districts (financially? with supplies? with expertise?), and “Rose’s district was advised to join with neighboring families in Fairfield in support of a union school.”

(Elsewhere, Whittemore’s history lists a George Rose from Waterville who served during the winter of 1839 in a militia unit raised in Fairfield and Waterville for the Aroostook War.)

By 1806, Wyman wrote, the education appropriation was increased to $600. That year, too, voters elected a five-man committee to inspect Waterville’s schools during the following year. Wyman commented that two members, Dr. Moses Appleton and Hon. Timothy Boutelle, were Harvard graduates; other sources say Appleton graduated from Dartmouth College, Class of 1791.

Wyman (like Kingsbury) listed family names of the 145 students in District 1 in 1808. He said they came from “Main, Silver, Mill, College, Water and lower Front streets.” Except for Mill Street, these are current names of major streets in downtown Waterville.

In 1808, Wyman said, the streets were “rough roads,” running through “an area still largely covered with woods, and used mostly for pasturage.” He listed two schoolhouses, “the little old yellow one close by the town hall, and the brick one on College street,” farther north along the Kennebec.

Voters at an 1812 town meeting made a decision that Wyman said recognized “the importance to public schools of official inspection.” They chose Appleton and Daniel Cook “visiting inspectors,” directed to visit every public school at least once in the winter term, and in the summer “if they thought proper,” and to tell each schoolmaster “the most proper mode of instruction.”

Appleton and Boutelle were two of the five 1821 school committee members Wyman named. Appleton was elected again in 1826, when, Wyman said, the committee had three members.

By then voters had approved paying school committee members “a reasonable sum” for their work, and in 1827 Appleton got $6. That year, too, voters approved a long motion by Boutelle that considerably expanded the men’s responsibilities.

Committee members were now required to prepare a detailed annual report. It was to cover how much each district spent and what for (specifically, expenditures for schoolmasters, for schoolmistresses and for wood); teachers’ names, wages and lengths of service; the number of students, what kinds of textbooks they had and what subjects they studied; the committee’s opinions on the quality of each school; and anything else committee members thought useful or interesting.

Wyman surmised it was because of the reporting requirement that committee members’ annual stipends went up to eight dollars in 1828.

In 1828, too, he wrote, the boundaries of Waterville’s 13 school districts were described in such detail as to take up three pages in town records. For years thereafter, he said, almost every town meeting included a vote on “setting off certain persons from one [school] district to another. This business and the laying out or discontinuance of roads furnished a never-failing subject for discussion and action.”

The comprehensive reports gave historian Wyman a surplus of material to choose from. His reports for the rest of the century are fragmentary, based apparently on his estimates of importance and interest.

In 1829, Wyman found, voters approved $900 for schools for the year, higher by $200 than any prior appropriation.

The 1834 school committee consisted of three ministers, Rev. Calvin Gardner (Universalist, who served his church from September 1833 to January 1853), Rev. Samuel F. Smith (Baptist, author of America, who served in Waterville from Jan. 1, 1834 to early 1841) and Rev. Jonathan C. Morrill (whose name is listed nowhere else in the Waterville history index and whom your writer could not find elsewhere).

Wyman wrote nothing about what this committee did.

By 1836 Waterville had 1,049 students in 14 school districts, and 26 teachers for the year. District 1 was the most populous, with “212 scholars on its census roll” – and an average attendance of 50.

In that district, one of the men was paid $26 a month for 18 weeks, and one of the women $14 a month for 23 weeks. Her pay, Wyman commented, “was more than was paid to some of the male teachers.” Six other districts paid female teachers $4 a month.

The most common school term was 22 weeks, longer in “the village schools” and somewhat shorter in “the smaller districts,” one of which had only 14 pupils.

Wyman summarized several years of arguments over whether and where to build new school buildings. A long-debated schoolhouse on the Plains, the area along Water Street south of the Kennebec River bridge, was authorized in 1846 “at a cost of $250”; and voters further agreed “to furnish two school rooms in the town hall.”

Some of the disputes were between residents of Waterville’s north and south ends. In 1853, Wyman wrote, a four-man committee created a 10-man committee that proposed a brick schoolhouse in each end; the idea was accepted.

The southern building was near the site of the present Albert S. Hall school, at 27 Pleasant Street, two blocks inland from the Kennebec.

The northern schoolhouse was on the lot that by 1902 was occupied by North Grammar School, opened Feb. 28, 1888. The 1853 building had been moved to College Avenue and was described as “a brick tenement.” After being relocated, it had been used as a school until the Myrtle Street School opened in 1897.

Wyman called the Myrtle Street School “in most respects the best school building in the city” in 1902.

A Dec. 4, 1981, report on the Waterville Fire and Rescue website locates the Myrtle Street School at the end of Myrtle Street, which dead-ends westward off College Avenue. The report is of a suspicious two-alarm fire; it says the three-story brick building, by then a warehouse for used tires, was gutted and one firefighter was slightly injured.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!