Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Fires were common in 19th century

by Mary Grow

Readers might remember that this historical series started at the end of March in reaction to the pandemic, to divert readers’ minds and fill a page in the newspaper. What plan there was at the time included stories about disasters, not only plague and pestilence but fires, floods, wars and other cheerful topics. Given California’s situation, this week seemed appropriate for a story on fires in some of our Kennebec Valley towns.

Fires were common in the 19th and early 20th centuries, especially mill fires, according to local histories. Specific causes are seldom given. In the days before organized fire-fighting companies, municipal or volunteer, consequences were often severe.

The 200th anniversary history of Fairfield has a chapter titled “Disasters,” with fires a major topic. By the 1830s, the town had multiple mills on the west shore of the Kennebec River behind the present Main Street, by the dam across the river and on Mill Island at the east end of the dam. Three major mill fires occurred before the end of the century.

The first was on Oct. 10, 1853. Three adjoining sawmills in 366 feet of building burned, with several smaller enterprises, including a factory that made curtain-sticks and another, where the fire started, that made pails. Henry Newhall’s saw and grist mill survived.

The town fire department was organized in May 1856. From then on Fairfield, unlike some nearby towns, had increasingly sophisticated equipment and trained people to fight fires.

In 1860 some shops burned. The compilers of the bicentennial history considered the fire noteworthy because it was the last time firefighters used the “Mog’s Trough hand-tub fire apparatus” the town bought some 30 years earlier.

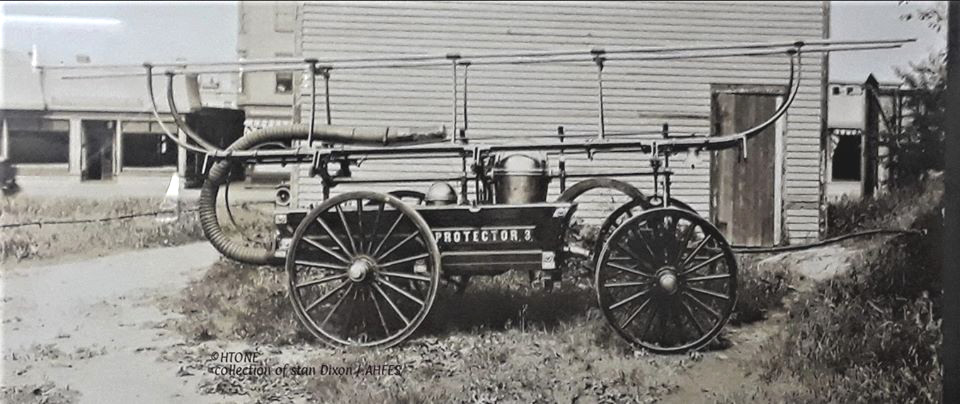

Online photos of the Mog’s Trough show a long shallow tub slung on four large wheels, with overhead piping and other machinery. One photo is dated 1821; another is of a hand-tub that once belonged to the Waterville, Maine, fire department.

In 1861 and again in 1873 the wooden trestle that carried the railroad tracks over the Kennebec between Fairfield and Benton burned.

On July 21, 1882, the second major mill fire took three sawmills, two planing mills, four other businesses and several houses. The weather was dry, the wind was blowing, and for a time it looked as though the entire downtown would go up in flames. The chroniclers say it was in response to this disaster that the town bought an Amoskeag steam fire engine, paying about $4,000 for it.

The Amoskeag was invented in the 1850s by a New Hampshire man named Nehemiah S. Bean; it and its rivals soon replaced the hand-tubs. The Fairfield history, published in 1988, says the Amoskeag was still at the Fairfield fire station; a collection of historic photographs found on line under the Fairfield Fire Department shows a steam fire engine in the late 1940s.

On Aug. 21, 1883, some of the wooden stores on Fairfield’s Main Street burned down. The history-writers speculate that this fire led to construction of brick replacements.

On Aug. 21, 1895, the third mill fire started in one mill’s boiler room. The dramatic account in the history describes dry wooden buildings with drifts of bark and stacks of finished lumber, oil-soaked lower floors, a hot day with the mill workers dismissed at noon to attend a big racing event at Fairfield’s trotting park on the west edge of town. Once the flames were spotted, town firefighters were supplemented by mill workers and ordinary citizens who fought the fire or loaded wagons with lumber to save it. Waterville sent a steam pumper and a fire crew; Somerset Mills at Shawmut sent teams and men. The mills burned to the ground anyway, and this time were not rebuilt.

In April 1911, a large sawmill built in Shawmut in 1908 burned. The owners opened a replacement mill on the site in November 1911; it burned within a week.

On Sept. 21, 1907, Lawrence High School opened on High Street, across from the Memorial Park. On Feb. 15, 1925, its interior was destroyed by fire. The brick building was rebuilt; it reopened the next spring and served until supplanted by the new high school on School Street on Sept. 7, 1960. It is now a primary school.

On Jan. 8, 1956, a grocery store with apartments above it at the corner of Main Street and Lawrence Avenue burned.

On March 14, 1966, the last mill building on Mill Island, owned by American Woolen Company, burned.

China is another Kennebec Valley town with a fire-filled history: each of its four villages has suffered at least one major fire.

The 1872 South China fire began around midnight April 24, in Wyman’s store on Main Street. It burned 22 buildings, including Theodore Jackson’s blacksmith shop (and his carriage manufactory on the second floor with a large second-story outdoor platform for new carriages to sit while their paint dried); two other blacksmiths’ shops; a tavern; a hotel; several stores, one of which housed the village post office; and several houses. Most of the giant elms that shaded Main Street were killed.

Milton E. Dowe described the Branch Mills fire of June 26, 1908, in his 1954 “History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1804.” It started about 11 a.m., on a pleasant spring day when most men were working in the fields, in the Dinsmore mill in the middle of the village. Sparks spread the fire eastward along the north side of the main street; it turned and came west along the south side.

Hastily assembled residents tried to fight the fire at the mill and to rescue goods from the other buildings. Possessions piled on lawns or in the street burned as the fire reversed. By 2 p.m., Dowe wrote, the wooden bridge across the West Branch of the Sheespcot River and 26 buildings, including a general store, a meat store and a large hotel, were destroyed. Other sources put the number of buildings lost at 16 or 50.

In his later book, “Palermo Maine Things That I Remember in 1996,” Dowe adds two details. Thomas Dinsmore, he wrote, saved his house from the fire by sitting on its roof with a bucket of water and a dipper to douse falling sparks. And the damage to the base of the Old Settlers’ Monument dates from the fire: someone put a rescued mattress there and the mattress burned.

After the fire, people used an alternate route downstream to ford the river until a metal bridge was built. The post office and some of the businesses reopened in scattered buildings on the outskirts of the former town center. Rebuilding began with Elon Kitchen’s new store near the stream, west of the present Grange Hall.

Dowe mentions three other fires that took commercial buildings: around 1885 a blacksmith and a carpenter lost their shops; in April 1916 two stores and a house burned; and on Oct. 1, 1933, Elon Kitchen’s building, by then Cain and Nelson’s store, burned down.

Weeks Mills had two significant fires in the first decade of the 20th century. The first, in September 1901, burned the village’s hotel and two stores. Another fire on May 26, 1904, burned five buildings on the south side of Main Street, including the partly-rebuilt hotel, and two stores at the top of the north side of the street. Another store downhill from the burned ones and mills along the stream escaped.

The hotel in Weeks Mills was rebuilt yet again and operated intermittently as a hotel through the first half of the 20th century, serving traveling salesmen and sometimes Wiscasset, Waterville and Farmington railroad crews stranded by winter storms.

On the outskirts of the village a factory canning corn and, in season, apples ran from early in the 20th century until 1931. In 1918 part of the factory burned. The owners invited area residents to help themselves to cans of corn, which were fed to animals and people.

Near the canning factory a former potato house became a general store after World War I. This building also burned, probably in 1932.

China Village’s commercial district in the 19th and 20th centuries was at the north end of Neck Road and the south end Main Street. Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history mentions several 19th-century fires, none as comprehensive as the other three villages suffered.

In the 20th century, a building that had started life as a cheese factory in 1874, been moved to Main Street and converted to a G.A.R. hall around 1899 and later become a garage burned in 1923. A larger fire started in the Jones and Coombs bean-cleaning plant in August 1961 and destroyed the plant and the Fenlason store next door.

Three of China’s four villages have their own volunteer fire departments. Branch Mills depends on the Palermo department, whose fire house is located in the village. South China’s department was organized in the spring of 1934, China Village’s in the spring of 1943 and Weeks Mills’ in the spring of 1949.

In the fall of 1947 many wildfires burned thousands of acres in Maine, destroying or significantly damaging nine towns, the so-called Millionaires’ Row on Mount Desert Island, the Jackson Laboratory and more than 1,000 houses and seasonal homes.

One of the fires was on Church Road in Sidney, which runs west off West River Road and, according to the current Google map, dead-ends east of Interstate 95. Alice Hammond wrote in her history of Sidney that fighting it took a long time, because the town lacked equipment and organization. As a result, some Middle Road residents began talking about the need for a volunteer fire department.

Two years later, on Oct. 14, 1949, a resident named Otis Bacon saw smoke as he drove past a house. He alerted the homeowners and neighbors, but there was still no organized fire-fighting effort, and three families lost their homes.

On March 21, 1950, Hammond wrote, Bacon called a meeting at the schoolhouse on Pond Road to start a neighborhood volunteer fire department. Twenty-one residents organized themselves as the Lakeshore Volunteer Fire Department, raised money, accept a donated lot, cut trees and sawed lumber to build a firehouse.

Meanwhile, residents of other parts of town mobilized to get a warrant article for the March 6, 1950, town meeting requesting $300 for each of three volunteer fire departments, covering Pond Road, Middle Road (the Center Sidney department) and River Road (the West River Road department).

In addition to large fires, our towns have suffered hundreds of individual house fires, costing residents their irreplaceable heirlooms and other possessions, their sense of security and in worst cases the lives of their pets or family members. Esther Bernhardt’s daughter-in-law and granddaughter have immortalized one of these fires in the “Anthology of Vassalboro Tales” Esther and Vicki Schad published in 2017.

Kimberly Bernhardt was the sixth generation to live in the Bernhardt farmhouse on Priest Hill Road; her daughter, Bethany Karen Bernhardt, was the seventh. Bethany wrote that a week before Christmas in 2006 a fire started in the kitchen and the smoke made the building uninhabitable.

It was a dreadful experience, Bethany wrote, but the consequences were heartening. Bernhardt family members in two neighboring houses came to help, of course; and so did dozens of other Vassalboro residents, some friends and some who barely knew the family. They brought food and other necessities; they helped clean up debris and tear down the ruined building; they supervised as a new house went up.

Bethany’s essay is titled, Home Is Where the Heart Is.

Main sources

Bernhardt, Esther, and Vicki Schad, compilers/editors Anthology of Vassalboro Tales (2017)

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 (1954)

Dowe, Milton E., Palermo Maine Things That I Remember in 1996 (1997)

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988)

Grow, Mary M., China Maine Bicentennial History including 1984 revisions (1984)

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992)

Websites, miscellaneous

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!