Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Historic listings – Part 2

by Mary Grow

Augusta Part 2

As mentioned in the first article on historic places in Augusta (see The Town Line, Jan. 7), four are on the National Park Service’s Register of National Historic Landmarks (as is Fort Halifax, in Winslow). The Augusta sites, listed in historical order, are the Cushnoc Archaeological Site, Fort Western, the Kennebec Arsenal and the Blaine House.

All except the Blaine House are on the east bank of the Kennebec River. Fort Western is the northernmost, just off Cony Street, northwest of City Hall.

The Cushnoc Archaeological Site is southwest of City Hall, north of the waterfront park. The old Arsenal building is south of the Route 202 bridge.

Wikipedia dates the Cushnoc archaeological site to 1628 and describes it as the location of a trading post built by English settlers from the Plymouth Colony. The name Cushnoc is an Anglicized version of a native word meaning “head of tide.” Under a patent from London, post officials traded with the Kennebec Valley Abenakis, exchanging corn and other agricultural and manufactured products for wild-animal furs.

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, says no description of the post survives. He surmises it was a wooden building, with a bark or wood roof and window-panes of oiled paper, and was surrounded by a high wooden fence.

In 1634, an interloper from the Piscataqua Plantations at the mouth of the Piscataqua River named John Hocking tried to share the trade. He sailed past the post and anchored upriver. John Alden and John Howland from the Mayflower emigrants were in charge of the post. Howland, who was about six years older than Alden and previously holder of several offices in the colony’s government, ordered Hocking away.

Hocking refused to leave, so Howland sent three men from the post in a canoe to cut his ship adrift. According to the dramatic account by Robert F. Huber in the Howland Quarterly, the quarterly journal of the Pilgrim John Howland Society (first published in 1936), the current bore the canoe away after the men cut only one cable. Howland added a fourth man, Moses Talbot (or Talbott, in Huber’s story), and sent them out again.

When Hocking threatened them with firearms, Howland repeatedly called to him not to shoot them – they were only obeying orders – but to shoot him instead. Nonetheless, Hocking shot Talbot in the head; another man in the canoe promptly shot Hocking, who died instantly.

Hocking’s crewmen reported his death to England, failing to mention that he had fired the first shot. Investigations followed, creating concern about British interference in colonial affairs and a jurisdictional disagreement between the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies. The investigators vindicated Howland as representing the owner of exclusive trading rights.

By 1661, profits were dwindling. The original traders sold their license and the premises to other Boston merchants, who kept the post going sporadically for a few more years.

Kingsbury quotes a source who said overgrown remains of the trading post building were still visible as late as 1692.

Excavation of the site began in 1984. Over the next three years, experts outlined the wall that surrounded the post and found postholes where there had been buildings. Wikipedia lists artifacts from the site including “tobacco pipes, glass beads, utilitarian ceramics, French and Spanish earthenwares, and many hand-forged nails.”

The archaeological site has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1989 and on the list of National Historic Landmarks since 1993.

Fort Halifax, in Winslow, and Fort Western, in Augusta, were both built in 1854, as was the road between them. Which fort was built first is not entirely clear. Kingsbury says unequivocally Fort Halifax was started first and Fort Western second, as an auxiliary. The Fort Western website says construction of that fort was finished in October 1754. Several sources say Fort Halifax construction began on July 25, 1754, and was not finished until 1756.

Fort Western was built by order of the Kennebec Proprietors, also called the Plymouth Company, the organization of first British-based and later Boston-based landowners mentioned in several previous articles (see especially The Town Line, July 2, 2020). The fort was sited just upriver from the former trading post site. It was intended as a supply depot for Fort Halifax, 17 miles farther inland, and as protection for settlements the Proprietors hoped to create.

According to the on-line Maine encyclopedia, the fort was named to honor Thomas Western, a resident of Sussex, England, who was a friend of Massachusetts Colonial Governor William Shirley.

The website for Fort Western gives a history of the fort in the context of the “great contest between cultures” going on in the 1750s. British from Massachusetts and French from Québec both sought influence over the Kennebec River Valley and the Natives who lived there.

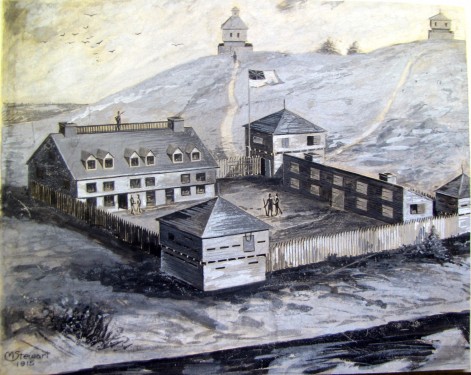

Wikipedia describes Fort Western as a rectangular palisaded area about 120-by-220 feet. It was built on a hill, so that its defenders could see more than a mile up and down the Kennebec River.

There were 24-foot-square blockhouses on the southwest and northeast corners and 12-foot-square watch towers on the other two corners. The main house, two stories high, was 32-by-100-feet; a diagram shows it along the east side of the enclosed ground.

Kingsbury’s description adds an outer and sturdier palisade 30 feet from the inner one that started at the river on both ends and enclosed three sides of the fort.

A July 24, 2020, Kennebec Journal article says the main building’s walls were (and are) a foot thick, built from timber floated upriver from Richmond. Two 600-pound cannons in the second story could fire four-pound balls as much as a mile.

Captain James Howard from Massachusetts was the first fort commander, with his sons, Samuel and William, and a company of 15 men, relocated from Fort Richmond farther down the Kennebec.

Supplies came from Boston as often as four times a year on schooners and sloops that navigated the river as far as the head of tide. From Fort Western soldiers took them to Fort Halifax in smaller, flat-bottomed river boats or on sleds over the crude road along the east bank of the river.

When they were not moving supplies, the men spent their time on what the Fort website calls routine duties – collecting firewood, feeding themselves and repairing boats.

The fort was never attacked by either Natives or the French. At least once a supply boat was fired on from the wooded river bank. And one member of the garrison, a private named Edward Whalen, was captured in May 1755 as he carried dispatches north. The website says he remained a captive, first in North America and then in France, until he was exchanged in 1760.

After British forces captured Québec in 1759 during the French and Indian War, the Kennebec was more peaceful, even though the war was not formally ended until the 1763 Treaty of Paris. The already small Fort Western garrison was reduced further, but the fort was manned until late 1767.

In 1769, Howard bought the fort and about 900 acres of land around it, for 270 British pounds, and became the first permanent settler in the area. A website called Legends of America says he and his sons made the main building into a house and a store. Son William and his wife Martha moved in around 1770; James’s brother John joined them later.

The Proprietors’ efforts to encourage settlers bore fruit after the region became safe. The Howards’ store prospered; they formed a shipping company, S & W Howard, that promoted trade with Boston; and Kingsbury says the small community welcomed the sawmill James Howard built on Howard’s Brook (now Riggs’ Brook), a mile north of the fort.

The Howards also trapped and sold alewives during their migrations to and from upriver spawning grounds.

Kingsbury says in 1770 James Howard built a large and elegant house that became “the manor house of the hamlet.” As the settlement’s second magistrate, in 1763 he officiated at Cushnoc’s first wedding, the marriage of his daughter Margaret to Captain Samuel Patterson. Later he served as a judge of the court of common pleas. He died May 14, 1787, aged 85.

The Legends website says James Howard’s son William lived in the former fort until he died in 1810. Kingsbury lists William Howard – this writer guesses the same William Howard – as Augusta’s first treasurer, elected at the town’s organizational meeting April 3, 1797, and credits him for first envisioning, in 1785, the dam across the Kennebec that was built in 1837. William Howard was succeeded as treasurer in 1802 by Samuel Howard (probably William’s son, born 1770, died 1827).

As previously related, Benedict Arnold and his men stopped at the fort on their way to Québec in September 1775, the last military use of the premises (see The Town Line, Jan. 7, 2021). The Legends website says the men camped outdoors while Arnold and four other officers were accommodated indoors. In addition to their own business as they transferred to Major Reuben Colburn’s bateaux, the soldiers found time to make repairs to the building.

When a public meeting was held, the fort was the site. The area around the fort was the northern village when the Town of Hallowell was created in 1771, and town meetings were held in the fort until voters approved building a town meeting house in 1782.

After the 1770s, the palisades and then the blockhouses were torn down. Kingsbury says the southwestern blockhouse stood until around 1834. What remained of Fort Western was included in Augusta when Augusta split off from Hallowell in 1797.

At some time, Wikipedia says, the Howard family sold the former fort and the main building became a tenement – not merely a tenement, according to the Legends website, but the center of a slum neighborhood whose inhabitants supported themselves by selling liquor illegally, creating “an unsavory menace to the city.”

Publisher Guy Gannett (see The Town Line, Nov. 12, 2020) was a Howard descendant, the Legends site says, and he bought the former family home in 1919. In 1920 he and his family restored the main building and built a new stockade (rebuilt again in 1960) and two blockhouses. The Gannett family later donated Fort Western to Augusta.

As the oldest wooden fort in the United States, Fort Western has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1969 and the list of National Historic Landmarks since 1973. Now a replica of an 18th-century trading post, it is normally open to the public from June through October.

Illustrations with the Kennebec Journal article mentioned above show trading post supplies, a bedroom with a curtained bed and more period furniture and household goods. These and other on-line contemporary illustrations show historic interpreters in 18th-century clothing welcoming visitors. The Maine Tourism site adds that the museum is a center for Kennebec Valley archaeological research and the home base for two companies of 18th-century military re-enactors, one named for James Howard.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

Websites, miscellaneous

Next: two more Augusta historic places/landmarks, the Arsenal and the Blaine House

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Hi! Love your work. I enjoy history & know quite a bit about this time period & you do a wonderful job! Thank you. Quick note – Margaret Howard actually married Captain James Patterson ( Not Samuel Patterson). Samuel was their son. I am a relative and – know the geneology well. Again – THANK YOU FOR YOUR HARD WORK!

“Fort Halifax, in Winslow, and Fort Western, in Augusta, were both built in 1854,” might be a writing error? Just number off, but it’s 100 years so it might matter. EXCELLENT article though. Thank you!