Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Immigrants

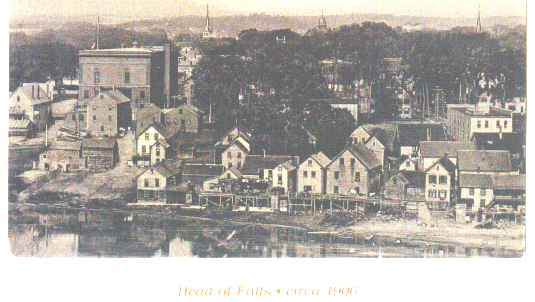

Waterville City Hall, upper left.

by Mary Grow

Middle Easterners, Waterville, & Irish, Augusta

The French-Canadians and the Irish were not the only groups coming to the central Kennebec Valley from other countries. Stephen Plocher wrote in his Waterville history (found on line) that in the 1860s, people he called “Syrian-Lebanese” from Syria (Lebanon and Syria were French mandates until 1943, when they became two separate countries) began arriving.

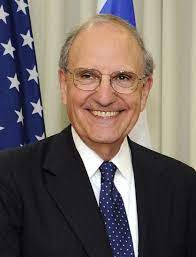

Their main settlement, shared with French-Canadian immigrants, was in the area called Head of Falls, on the west bank of the Kennebec between the railroad track and the river, east of City Hall. Former Maine Senator George Mitchell, whose mother was Lebanese by birth and father Lebanese by adoption, grew up in Head of Falls.

He wrote in his book The Negotiator (see Box 2) that the area was only about two acres, bounded by the railroad, the river and the Wyandotte Worsted Textile Mill where many residents worked. The land was crowded with apartment buildings and small houses, and the buildings were crowded with people.

Mitchell wrote that one group of houses was on the bank of the Kennebec. Another group was above them at the top of a short steep hill. In winter, the gravel path between them became a sledding run for Head of Falls children (where Mitchell suffered a broken leg in an accident the winter he was five years old).

Head of Falls was first home to French-Canadians. Plocher said the earliest Middle Eastern immigrants worked as “peddlers,” but they soon found jobs with the railroad and, as manufacturing expanded, in Waterville’s numerous, mostly water-powered, mills.

The Syrians were Maronite Catholics, and joined the Franco-American church. Mitchell explained that the Maronites are named to honor a fifth-century hermit priest in what is now Lebanon; they have been part of the Roman Catholic Church since the 16th century.

Reuben Wesley Dunn’s chapter on manufacturing in Whittemore’s Waterville history listed some of the employment opportunities in the last half of the 19th century.

The Waterville Iron Manufacturing Company started in the 1840s on Silver Street. After an August 1895 fire, the company, by then Waterville Iron Works, reopened farther north, on the Kennebec north of Temple Street.

The first cotton mill, according to Dunn, was the Lockwood Company’s, planned and built over several years and producing its first cloth in February 1876. Its immediate success led to opening a second, larger mill early in 1882. When Whittemore and his colleagues wrote their history in 1902, the Lockwood mills had about 1,300 employees and an annal payroll of about $415,000.

The Hathaway Shirt Factory was started in 1849. By 1902, according to Dunn, it employed between 150 and 175 people to run 100 sewing machines, with an annual payroll around $60,000.

The company first named Riverview Worsted Mills, soon to become Wyandotte Worsted, was organized in 1899 and began operations in February 1900 in a mill a bit north of Temple Street. Its product, Dunn wrote, was “fine fancy worsteds for men’s wear.” In 1902 the company had 80 looms “of the latest and most approved pattern”; it was moving toward 300 employees and a $150,000 annual payroll.

Hollingsworth & Whitney Paper Mill

The large Hollingsworth and Whitney mill (later the Scott Paper mill), in Winslow, opened in 1892, also needed workers. Dunn wrote that the facility started with a groundwood mill and a paper mill, and added a sulphite mill in 1899. (Groundwood is, as the name says, ground-up wood, or wood pulp, used to make paper. Sulphite is one of several additions that can make paper whiter, stronger or otherwise more useful for specific purposes.)

By 1902, Dunn said, the mill employed 675 men and the payroll was about $360,000 a year.

Dunn included the Winslow mill in a history of Waterville because, he wrote, it “contributes in so high a degree to the prosperity of our city.” To make this contribution possible, the footbridge known as the Two Cent Bridge was built in 1901, to let Waterville residents, especially those living in Head of Falls, “commute” to work in Winslow. (See Box 1)

Lebanese immigration continued in the 20th century, Plocher wrote, as more people joined friends and relatives and found jobs. Enough more Maronite Catholics arrived to organize their own church. The first Maronite priest began conducting services in Arabic in 1924; St. Joseph’s Maronite Catholic Church at the intersection of Appleton and Front streets was built in 1951.

Waterville’s urban renewal in the early 1960s eliminated the Head of Falls settlement, which by then, Mitchell said, most people would have labeled a slum. The Wyandotte Woolen Mill moved to West River Road and the housing was demolished.

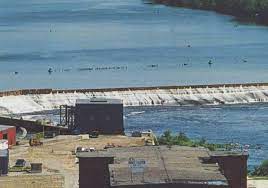

Edwards Dam, on Kennebec River

In 2016 former Colby College Dean Earl Smith wrote a novel titled Head of Falls about a teen-age Lebanese girl growing up in Head of Falls in the 1950s. In the Central Maine Morning Sentinel for Nov. 13, 2016, he told reporter and columnist Amy Calder that he wrote the novel “to pay tribute to the Lebanese people and to provide a testament to their lives.”

He continued, describing the area in the 1950s: “It has always fascinated me that in this community everyone got along well. They were Arabic and there were Jews and French and Irish — they all had their separate neighborhoods. It’s sort of nice to be a community where we don’t have these kinds of tensions at all. That’s what Waterville was like.”

Russian and Polish Jews also came to Waterville, Plocher added, leading to the organization of Beth Israel Congregation in 1902. Services were first held “in the north end fire station,” he wrote; the first synagogue opened in 1905. The current Upper Main Street building dates from 1957, according to the website.

Augusta was the other major manufacturing hub in the central Kennebec Valley. According to Augusta’s Museum in the Streets, immigrant workers were French-Canadians and Irish; Middle Easterners are not mentioned. (See the related article in the May 12 issue of The Town Line.)

The Museum in the Streets says the “hard and dangerous” work of building the first dam across the Kennebec in 1834 and 1835 was done by French-Canadian and Irish workers. James North agreed in his 1870 Augusta history. Of the Irish, he wrote that many worked on the dam; others “made themselves useful in the various improvements going on about town.”

The Museum quotes Nathaniel Hawthorne’s description of the workers’ houses, when he visited Augusta in 1837 with Bowdoin College classmate Horatio Bridge. He called them “subterranean” in appearance, with sod roofs and turf walls.

To accommodate the Irish population, Augusta’s first Catholic services were held in 1836 in the former Unitarian church building on the east side of the Kennebec. In 1845, Thomas B. Lynch wrote in Kingsbury’s history, a new Catholic church was built on State Street; it was dedicated September 8, 1846.

North cited a census taken in Augusta in 1836 (not the federal decennial census, and he did not explain it) that showed a population of 6,069, including 54 Blacks and 407 “Foreigners not naturalized.”

In 1845, North wrote, Augusta began a fast industrial expansion mostly based on the water power the dam supplied. A large cotton factory was started in 1845 and went into operation in November 1846. Six sawmills and “a large and expensive flour mill” began operations around the same time, and other factories followed.

The owners of the cotton factory built workers’ boarding houses and sold by auction 50 50-by-100-foot house lots on about 5.5 acres “on the table land above the factory.”

Another employment opportunity arose when the railroad was extended to Augusta, with the first locomotive arriving Monday, Dec. 15, 1851. North wrote that it came during a snowstorm and during a session of the Supreme Court, which had to be suspended because the “exultant and joyous” train whistle drowned out the proceedings.

Museum in the Streets says the various factories had 600 employees by 1858. The cotton mill alone employed 229 women and 61 men in 1860.

North described the by-then-City of Augusta as continuing to thrive until his book was published in 1870, despite dam washouts, fires, economic changes and a civil war. In contrast to Dunn and Plocher, he focused on the entrepreneurs, the financiers, the occasional political issues related to development and the building and rebuilding, and said nothing about the thousands of people who worked in the various mills and factories.

Ticonic Footbridge

The pedestrian bridge across the Kennebec River linking Waterville and Winslow was officially named the Ticonic Footbridge when it was built in 1901 for the Ticonic Foot Bridge Company, Wikipedia says.

The original bridge was carried away by a Dec. 15, 1901, flood. By 1903 it had been replaced.

When the bridge first opened, the fee to cross the river was one cent, collected at a tollbooth on the Waterville end. An on-line description of the bridge’s historic marker says the charge was doubled to pay for the 1903 rebuilding, and the bridge became known as the Two Cent Bridge or the Two Penny Bridge.

George Mitchell, whose family lived close to the bridge for the first few years of his life, wrote that children from Head of Falls became adept at sneaking past the toll collector for a free walk to Winslow. Early in the 1960s the Ticonic Foot Bridge Company gave the bridge to Waterville and city officials made it free for everyone.

The bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. The marker calls it “the longest [at 576 feet] and oldest wire suspension footbridge in America.

Selected contemporary sources

1) In the May 20, 2022, edition of the Central Maine newspapers, Amy Calder wrote about two Colby College seniors whose documentary about life in Waterville’s South End premiered at Railroad Square Cinema May 17. Her piece is titled Opening a door to Waterville’s South End.

The documentary by Charlie Jodka and Quinn Burke, available on Youtube, features interviews with people who grew up in The Plains.

George Mitchell

2) George Mitchell described The Negotiator as stories about his life, not a formal biography, and the description is accurate. Your writer recommends the book to readers interested in Maine, in government and politics or in this unusual man. (Former Senator Mitchell was profiled earlier in this series, in the July 23, 2020, issue of The Town Line.)

3) As your writer picked up a copy of Mitchell’s book at the South China Public Library, volunteer librarian Dale Kilian offered a small paperback titled War in the South Pacific A Soldier’s Journal (copyright 1995). The author was Thomas J. Maroon (1914-2002), a local man of Lebanese heritage who enlisted in the Maine National Guard in 1940 and fought in the Pacific theater for more than three years in World War II. Based on the informal diary he kept, it should appeal to students of military history; area residents will find many familiar names.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Mitchell, George J., The Negotiator (2015).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Plocher, Stephen, Colby College Class of 2007, A Short History of Waterville, Maine Found on the web at Waterville-maine.gov.

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!