Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Kennebec Proprietors

by Mary Grow

This series has repeatedly mentioned the Kennebec Proprietors. It is now time to backtrack to the 18th century, to find out who they were and why they are mentioned in almost every history of the State of Maine and in most local histories of Kennebec Valley towns and cities.

The initial group, the Plymouth Colony, was chartered in 1606 by King James I of England. The king gave it and its companion London Company, whose first settlers came to Virginia, control of most of eastern North America.

In a series of grants and sales in following years, the land went successively to the new Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts; to the Council for New England (1620-1635, a London-based joint stock company headed by Ferdinando Gorges, with a royal charter to promote American settlement) and to the Boston-based New Plymouth Company.

The Council for New England set up other land companies, including the Pejepscot Company, which was given a claim on the lower Kennebec and extended it upriver to Swan Island and Richmond, overlapping with the Kennebec Proprietors’ claim on the southwest.

On the east, the Waldo Patent, named for Bostonian Samuel Waldo, also overlapped in what is now Palermo and the surrounding area. According to one on-line source, the land was a gift to Waldo from Massachusetts for his help in deterring a 1729 attempt by King George II to establish a crown colony that would have been exempt from Massachusetts’ jurisdiction. Another source says the Surveyor of the King’s Woods (the person responsible for marking and protecting trees large enough to make masts for British Royal Navy ships) made a nuisance of himself, Waldo persuaded his British superiors to fire him and the appreciative heirs of a 1630 Waldo Patent rewarded Waldo with acreage.

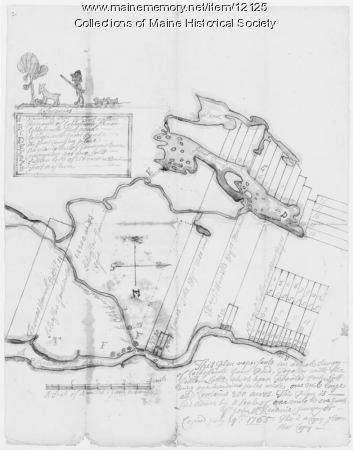

The Plymouth grant extended up the Kennebec from Merrymeeting Bay to the falls at Norridgewock, already known as a Native and French settlement, and for 15 miles on each side of the river. Since the river’s windings were not well documented and the surrounding land not well known to Europeans, there was considerable uncertainty about the size (supposedly about 1.5 million acres) and shape of the grant.

The New Plymouth Company, with a gradually changing membership as newcomers bought or inherited shares, did little. In the fall of 1661, four Boston merchants bought the land rights for 400 pounds sterling. The beavers, basis for earlier fur trading, were by then in decline; the Bostonians’ plan was to use the timber resources, including as a basis for building ships, and in the future to encourage agriculture. They, too, failed to accomplish significant development.

Upriver settlement was discouraged by a series of wars with the Natives from the 1670s to 1763, including the four-war series beginning in 1688 that Americans call the French and Indian Wars. Maine Natives had support from the French, who had settled along the St. Lawrence River and disputed the British claims in northeastern North America.

The 1763 Treaty of Paris between the European rivals ceded Canada to the British and promoted settlement in Maine. (Many historians add that it contributed to Britain’s loss of the American colonies, because removal of the French threat made colonial leaders believe they no longer needed British military protection).

In the 1740s, a man named Samuel Goodwin, who had inherited half of a third of a quarter of a Plymouth Colony share, became interested in development along the Kennebec. After much searching, he found the original charter, which had been missing for decades, and in 1749 he and other heirs brought the New Plymouth Company back into business, beginning with a Sept. 21 organizational meeting in Boston.

In 1753, the Massachusetts General Court re-awarded the grant to “The Proprietors of Kennebeck Purchase from the late Colony of New Plymouth.” The name is shortened by historians to Kennebec Proprietors, Kennebec Company or Kennebec Purchase Company (sometimes Kennebeck) or Plymouth Colony or Plymouth Company, used interchangeably in discussing the period from 1753 to 1818, when the company disbanded.

Because settlement was slow to expand upriver to Norridgewock, the western boundary of the Kennebec Patent was not a big source of contention. The downriver line was intermittently challenged, especially by the Pejepscot Proprietors, leading to legal proceedings in America and in London.

In 1757, the boundary question was referred to a panel of lawyers. They confirmed the upriver boundary and defined the downriver end of the Kennebec patent on the east side of the river as the present northern boundary of Woolwich. The western boundary was defined as Lake Cobbaseconte (now Cobbosseecontee).

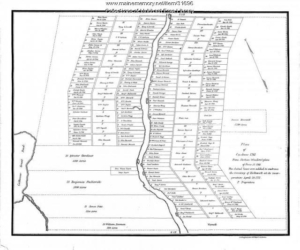

The Kennebec Proprietors brought settlement to much of the central Kennebec River area. Surveyors laid out lots along both sides of the river for miles, defining the 15-mile boundaries. The population had increased so much that Lincoln County was separated from York County in June 1760. By 1775, when the American Revolution began, Hallowell (including Augusta), Vassalboro (including Sidney) and Winslow (including Waterville) were incorporated as towns.

The Kennebec Proprietors reserved some lots in each new town for themselves. Some they gave away to encourage settlement, some they sold. A typical lot contained 100 acres; typical deed requirements included building a house of specified size and clearing a specified number of acres within a specified number of years. A settler or his heirs might be required to stay on the land for a specified term – two, three or seven years, sometimes longer. Often deeds included an obligation to help lay out roads, or provide for a church and minister, or both.

A complication was that some of the land the Kennebec Proprietors claimed, surveyed and gave away or sold was already occupied by Europeans. Some had bought their holdings from Natives. Some had deeds from other Europeans. Some had moved onto and improved a vacant tract and claimed squatters’ rights.

Native deeds had been a source of misunderstandings for years. When a Native chief “sold” part of his tribal land, he believed he was giving the European “buyer” the right to share the land equally with tribal members; and the right was valid only for the lifetime of each party. The European believed he acquired the exclusive right to live on and change the land forever, and to sell or will it to someone else.

The history of Windsor offers an example of transactions between European claimants with no involvement with the Kennebec Proprietors. As described in Linwood H. Lowden’s history of the town, in 1797 Ebenezer Grover and associates hired Josiah Jones to survey about 6,000 acres on the west side of the West Branch of the Sheepscot River in southern Windsor. They ended up with 33 Oak Hill lots, some individually owned and some held in common.

These lots were occupied or bought by families who became southern Windsor’s first settlers. Lowden points out that Grover had no legal right to survey or sell the land; indeed, he says, many of Grover’s deeds warned purchasers that Grover and his associates would not help them if the Kennebec Proprietors challenged their titles.

Jones did other, smaller surveys elsewhere in town, and Isaac Davis surveyed at least once, in northern Windsor.

In January 1802 the Kennebec Proprietors asked the Massachusetts General Court to appoint commissioners to deal with the people they saw as illegal squatters. The Proprietors also had their own survey done, laid out their version of lots (usually, Lowden says, smaller than the originals) and offered to sell them to the settlers.

A political and legal dispute followed, during which some of the settlers paid again for their land and the Proprietors evicted others for non-payment. The Proprietors were unpopular, to say the least; their local representatives and their surveyors, being available, were threatened and had their property destroyed.

The culminating event of the “Malta War,” as it is often called (Windsor was named Malta from March 1809 to March 1821), came on Sept. 8, 1808. Surveyor Isaac Davis, hired by a settler to determine lot lines so the settler could pay the Proprietors, was heading a crew on Windsor Neck that included a resident named Paul Chadwick. Other residents, armed and disguised as Natives, intercepted the party and shot Chadwick, who died three days later.

Nine local men were arrested and sent to the county jail in Augusta. Disturbance continued as rumors spread of a planned attack on the jail to rescue them. On Oct. 3 a mob gathered on the east bank of the Kennebec; in response, authorities called out the militia and placed cannons to defend the bridge if necessary.

The accused were all acquitted in November 1809, an outcome historian Lowden thinks was the best choice to ease tension. He also suggests the men were after Chadwick specifically, because he had opposed the surveys and then hired on to help Davis; and he speculates they did not intend murder.

In neighboring Palermo, the Proprietors’ demands led inhabitants to petition the Massachusetts General Court for help. Legislators set up a commission early in 1802 that assigned three local men to value properties, subject to approval by the Proprietors’ agent, and assigned three surveyors to fix settlers’ boundaries. Local historian Millard Howard lists more than 60 families who bought their homesteads, mostly 100 acres, for prices ranging from $25 to $155.

Although the larger Sheepscot Great Pond area, including present-day Palermo and Windsor, hosted groups most actively and violently opposed to the Kennebec Proprietors’ effort to claim land they thought was rightfully theirs, other parts of the valley were affected.

In Vassalboro, for example, historian Alma Pierce Robbins writes that the presence of squatters who built cabins and cleared farmland before Nathan Winslow’s 1761 survey for the Proprietors started a century of legal disputes over land ownership. Additionally, she says, in Vassalboro and elsewhere the British Crown’s claim to any tree large enough to become a ship’s mast bred resentment, since landowners (legal or otherwise) were not compensated for the timber.

(Dean Marriner recounts the later history of one lot in Dr. John McKechnie’s 1770 survey of the Waterville-Winslow area. A century later, he says, a lot owner claimed his boundary, as shown on the McKechnie survey, was wrong. He and his neighbor disputed it for more than two decades; he went to court six times, allegedly spending over $15,000 on legal fees, and lost every time.)

The Kennebec Valley settlers’ problems with the Proprietors on whose property they lived ended after 1813. A Massachusetts Commission recommended and the General Court approved an agreement giving the settlers their disputed holdings and giving the Proprietors Saboomook Township as compensation. (Saboomook Township has no web listings. It might be Seboomook, the unorganized township north of Moosehead Lake that hosted one of Maine’s four German prisoner of war camps from 1944 to 1946.)

Main sources

Hammond, Alice History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 1992

Howard, Millard An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine Second edition, December 2015

Kershaw, Gordon E. The Kennebeck Proprietors 1749-1775 1975

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed. Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 1892

Lowden, Linwood H. good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine 1993

Marriner, Ernest Kennebec Yesterdays 1954

Williamson, William D. The History of the State of Maine from its First Discovery, A.D. 1602, to the Separation, A.D. 1620, Inclusive Vol. II 1832

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!