Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Towns and cities’ names – Part 1

by Mary Grow

This series has been geographically grounded, mostly, in specific places: 12 municipalities in the central Kennebec Valley. Your writer’s next topic is how each of these got its name.

As usual, there will be preliminaries, the first of which have taken up this entire introductory essay. They are a short detour along the coast and a summary of British settlement. Succeeding articles will include brief re-introductions of some of the people who came to the area in the 1700s.

Fishermen from Britain, France, Spain and Portugal were familiar with the Maine coast and coastal islands years before any significant number of Europeans thought of living here. The fishermen set up temporary camps to dry fish, repair boats and do other land-based activities.

Permanent European settlement started on the coast, obviously. Travel inland was mostly up rivers, since the tracks through the woods were familiar to the Native Americans, but not to the newcomers.

Both French and British monarchs were, at various times and to varying degrees, interested in this part of North America. The French tried to settle St. Croix Island, near the present Maine-Canada border, in 1604.

Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore summarized parts of the story of French influence in the Kennebec River valley in the 1902 centennial history of Waterville that he edited and partly wrote.

In 1603, Whittemore said, King Henry IV of France made a large grant of North American territory, from around present-day New York City to the northern tip of present-day Maine (and from the Atlantic to the Pacific), to Sieur de Monts (Du Mont, in James North’s 1870 history of Augusta). The territory was named Acadia.

De Monts and Samuel de Champlain explored Merrymeeting Bay, where the Kennebec and Sheepscot rivers meet, and in July 1604, Whittemore wrote, Champlain “set up a cross on the bank of the [Kennebec] river and formally claimed the territory as a part of Acadia.”

North called this episode “the first attempt of royalty to obtain foothold on the banks of the Kennebec.”

It was also a harbinger of the Franco-British rivalry for influence in the Kennebec valley that led to periodic death and destruction and slowed British progress inland. Charles Nash, in his chapter on Maine Native Americans in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, listed six separate Indian wars in Maine between 1675 and 1763.

One consequence was the obliteration of the Native culture, the Abenaki tribe called the Kennebecs or Canibas, headquartered in the early 1600s on Swan Island, in present-day Richmond.

British monarchs encouraged settlement by granting charters to companies of prominent men, of whom the Plymouth Company (and its successors) were most important to Maine. King James I granted these men, mostly from Plymouth, England, settlement rights to part of North America in 1606.

They in turn recruited settlers and provided ships and supplies. The expectation was that New World resources would be profitable.

The first British settlement in present-day Maine was the Popham Colony, at the mouth of the Kennebec, named after Sir John Popham, one of the Plymouth Company, and led by his nephew, George Popham.

The colony was settled in August 1607 and abandoned (Wikipedia) or partly abandoned (Robert P. Tristram Coffin, in “Kennebec Cradle of Americans”) in 1607-1608.

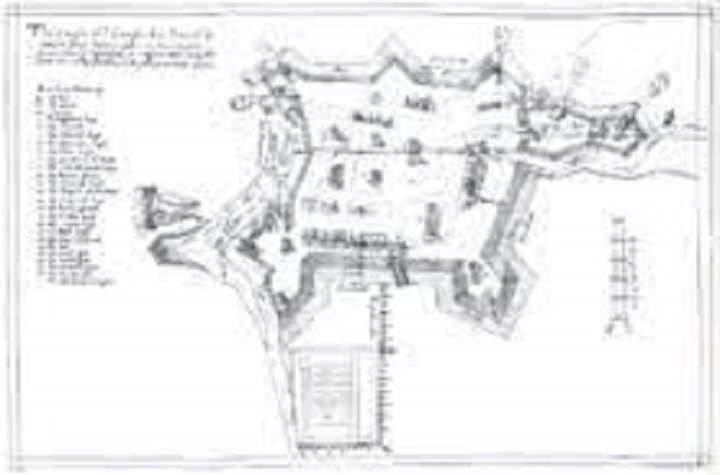

The colonists built a fort, named Fort George (Wikipedia and other sources) or Fort St. George’s (Coffin and other sources). It was in what is now Phippsburg – Wikipedia says about 10 miles south of present-day Bath. The Civil War Fort Popham, on the National Register of Historic Places, is “within sight of” the original colony, Wikipedia says.

Near the fort were a storehouse and colonists’ houses. The colonists started the ship-building industry on the Kennebec, with the 30-ton pinnace “Virginia of Sagadahoc.”

(Wikipedia explains that a pinnace was a boat or ship carried on a larger ship to use as a tender, ferrying people and supplies or going places the larger vessel couldn’t. A pinnace could be almost type of boat, propelled by sails, oars or both, with up to three masts and sometimes armed.)

The Popham colonists explored a short distance up the Kennebec. Wikipedia says they made contact with the Abenakis, but “failed to establish cooperation” with them. Coffin wrote the white men got as far as present-day Brunswick, where they found fertile land for crops (though it was too late to plant that year).

Coffin and Wikipedia say half the colonists took advantage of a supply ship to return to England in December 1607, discouraged by a Maine winter. Wikipedia says the remainder left for England in September 1608 in the supply ship and the “Virginia.”

Coffin (whose 1937 book your writer highly recommends) wrote that the “Virginia”, too, went to England in December 1607; and the 55 men who stayed behind became Maine’s lost colony. When the supply ship returned in the spring, he said, no one was there, though there were unexplained house foundations in the area.

Coffin surmised the men might have joined the European fishermen’s camps on Monhegan Island, not far from the mouth of the Kennebec, or the Abenakis up the river. He concluded:

“By all accounts, they were tough customers and could have made their beds anywhere. Very likely they stayed on this side of the Atlantic and were the original settlers, instead of the men of Jamestown of 1607.”

(Your writer is not sure about that last clause. Sources that give precise dates say the Popham colonists left England late in May 1607, a couple weeks after the Jamestown settlers landed, and reached future Maine in August 1607. Wikipedia says the sick, starving Jamestown colonists started back to England in 1610; but they met a “resupply convoy in the James River” and changed their plan. Maybe Coffin meant they were not the first permanent settlers?)

Coffin further surmised that well before the Plymouth Company existed, Englishmen were “homesteading in Maine” – fishermen, traders, “rapscallions of the first water seeking new fields.” He wrote: “Lots of the Maine settlers were men who did not care to put an address on their calling cards.”

North wrote that the failure of the Popham Colony did not discourage other explorers. In 1614, he said, John Smith (already famous for his role in the settlement in Jamestown) spent time on Monhegan Island, and named the mainland New England.

Smith’s voyage made a profit from furs and fish, and his upbeat 1616 account of the land he had explored encouraged the Plymouth Company.

The independence-seeking, probably minimally religious, mixed-nationality settlers Coffin described moved inland as the coast became more crowded. Others crossed the Atlantic to explore new opportunities.

The 1606 charter was supplanted in 1620 and again in 1629. Companies’ charters often overlapped geographically, creating later complications over land titles (for those who bothered about such legal frills).

In 1661, four men named Antipas Boies or Boyes, Thomas Brattle, Edward Tyng and John Winslow assumed control of the Kennebec Patent. Louis Hatch’s history of Maine says these four men and their heirs and associates organized “The Proprietors of the Kennebec Purchase from the late Colony of New Plymouth.” This group is usually called the Kennebec Proprietors.

Hatch added that the Massachusetts colony claimed control over Maine as far northeast as the Kennebec Valley from the 1630s on. King Charles I created the name Province of Maine in 1639, Hatch wrote.

* * * * * *

Turning now to the Kennebec River valley in particular, Whittemore wrote that on Jan. 13, 1629, the Plymouth Council (successor to the 1603 Plymouth Company) granted to the Plymouth Colony the Plymouth (or Kennebec) Patent.

This grant, when its boundaries were eventually agreed, gave the Plymouth Colony control over both banks of the Kennebec for 15 miles inland, between present-day Wooolwich and present-day Cornville. It covered about 1.5 million acres.

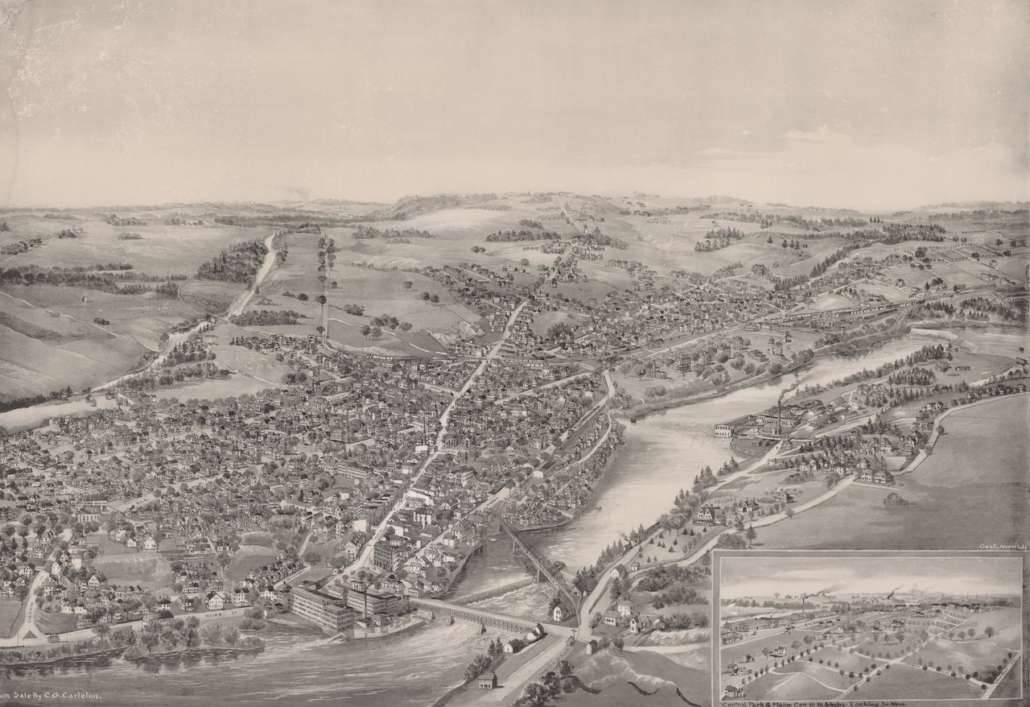

The Plymouth Colony set up three trading posts. The one farthest upriver was at Cushnoc, on high land on the east bank of the Kennebec in what is now Augusta.

This area had been for some time an informal meeting and trading place for Natives and Europeans. Different writers mentioned that it was at the head of tide; a traditional Native camping place; and convenient for Natives bringing the furs Europeans coveted.

The City of Augusta website (and other sources) date the Cushnoc trading post to 1628 (just before the Patent was granted). The website (and others) say the fur trade started well, but declined after 1634.

Lendall Titcomb wrote in his chapter in Kingsbury’s history that in 1652, the Plymouth Colony rented out the post for 50 pounds a year. Three years later the lease was reduced to 35 pounds a year, payable in “money, moose or beaver.” On Oct. 27, 1661, the Plymouth group sold Cushnoc to the four Kennebec Proprietors mentioned above.

Whatever remained of the building was probably burned in 1676, during an outbreak of fighting with French and Natives that drove most of the British out of the Kennebec Valley.

In 1939, the Maine Society of the Daughters of Colonial Wars marked the trading post site with a plaque that reads: “In commemoration of the first trading voyage of the Pilgrims of Plymouth to the ancient Indian village at Cushnoc on the Kennebec River, 1625, and on this site the establishment of their fur trading post with the Indians, 1628, Jown Howland in command, 1634.”

In 1754, the British built Fort Western near the former trading post site. In the 1980s, archaeologists found where the trading post had been, a little south of the fort, partly on the Church of Christ, Scientist, property.

They were able to outline the walls, and found some of the trading goods. Wikipedia lists “tobacco pipes, glass beads, utilitarian ceramics, French and Spanish earthenwares, and many hand-forged nails.”

The site has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1989. (See box.)

* * * * * *

In the valley of the Kennebec, Titcomb wrote, there was no organized settlement effort between 1661 and 1749. Some of the downriver towns were created: the town that is now Harpswell was settled in 1689; Bowdoinham, and as part of Bowdoinham Richmond, in 1725; Swan Island in 1750, added to Frankfort (now Dresden) when Frankfort was organized in 1752; Gardiner in 1754.

In August 1749, Titcomb said, the heirs of the 1661 foursome reorganized and, in June 1753, created the “Proprietors of the Kennebec Purchase from the late Colony of New Plymouth,” known informally as the Kennebec or Plymouth company.

In 1761, this group hired surveyor Nathan Winslow to lot out the riverside land between present-day Chelsea and Vassalboro and invited settlers. There will be more about the Winslow survey in subsequent articles.

Here are approximate dates of first settlements along the east shore of the Kennebec from Augusta to Clinton, from south to north: Augusta, Fort Western settled in 1754; Vassalboro, settled about 1760; Winslow, Fort Halifax settled in 1752; Benton, settled about 1775; and Clinton, settled about 1775.

Following articles will describe the founding, naming (and renaming) and early growth of these five municipalities and their neighbors.

Old Fort Western director seeks funds to reconstruct Cushnoc Trading Post

Two years ago this month, Old Fort Western Director Linda Novak announced plans to reconstruct Cushnoc Trading Post. The goal is to raise enough money by 2026 to complete the replica in 2028, the 400th anniversary of the original post. Anyone interested in learning more about or contributing to this project is invited to call Old Fort Western at 626-2385 weekdays between 8 a.m. and 4:30 p.m.

Main sources

Coffin, Robert P. Tristram, Kennebec Cradle of Americans (1937)

Hatch, Louis Clinton, ed., Maine: A History (1919; facsimile, 1974)

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892)

North, James W, The History of Augusta (1870)

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!