REVIEW POTPOURRI: How Music Grew in Brooklyn

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

How Music Grew in Brooklyn

Maurice Edwards; Lanham, Maryland; Scarecrow Press; published 2006; 380 pages.

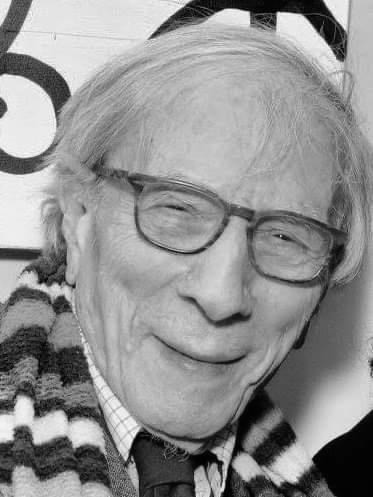

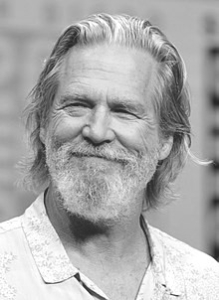

This hefty book of at least 10 pounds could rightfully be considered a coffee table book. A history of the Brooklyn, New York, Philharmonic, it was also a labor of love for its author Maurice Edwards (1922-2020) who had been involved with the Philharmonic since its official beginning in 1954, later becoming executive director before retiring during the mid ‘90s.

His successor in the executive position suggested that Edwards write a history of the orchestra, its connection with the Brooklyn Academy of Music and its impact on the lives of so many music lovers in the surrounding communities. He responded as follows:

“Not being a musicologist, a historian, or even a music journalist, I was flattered but a bit humbled by the very idea. Was I qualified for the job? Would that be true retirement? Was I not rather ready for a respite?

“Yet, realizing that I could never fully sever all relations with the orchestra I had lived with for so many years and indeed helped develop, I decided that maybe it was not such a bad idea after all, and I accepted the challenge.

“I soon found myself turning into a veritable ‘Phantom of the Orchestra’, haunting the Brooklyn Academy of Orchestra where the Philharmonic was housed until seven years ago [1999], plowing through the orchestra’s irregularly kept archives (often mixed up with the Academy’s), refreshing my memory through the perusal of old programs, board meeting minutes, newspaper minutes, newspaper articles and reviews, and interviewing some of the survivors of the rocky journey of this nonprofit arts organization through the wiles, guiles, and hazards of the for-profit business world. All of this began to tell its own story to me, namely, How Music Grew in Brooklyn: A Biography of the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra, and so I proceeded to record it.”

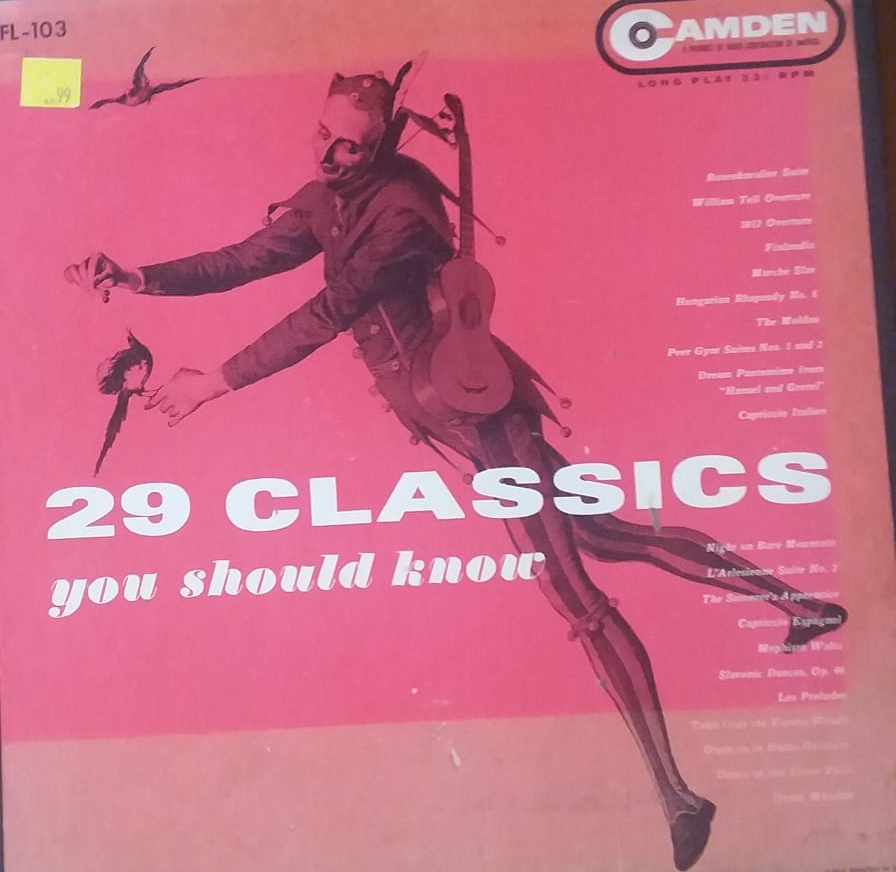

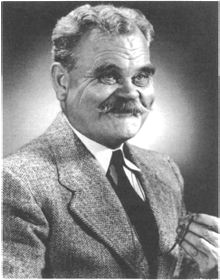

Prior to 1954, the classical concerts in Brooklyn were happening as early as the 1850s with the arrival of immigrants from Europe who were gifted performers needing a livelihood, the listeners who were eager to hear music and the wealthy patrons who bankrolled the concerts. Early conductors included the very colorful charletan Louis Antoine Jullien (1812-1860) and his protegé Theodore Thomas (1835-1905).

Jullien went to debtor’s prison after his return to France and rightfully for swindling would-be investors but was gifted as an orchestra trainer. Thomas was simultaneously music director of one of the earlier Brooklyn Philharmonics, the New York Philharmonic across the East River, and his own Theodore Thomas Orchestra; he provided ample work for his core players in all three groups, developed adventurous programs of works both old and knew and courted wealthy investors before he left for the Chicago Symphony position in 1890.

After 1954, the orchestra’s Music Directors were Siegfried Landau until 1971, Lukas Foss from 1971 to 1990, Dennis Russell Davies through 1996, and Robert Spano to 2004, each one of these Maestros gifted musicians and adventurous programmers who didn’t believe in playing it safe, unlike too many conductors of major orchestras in recent years who program the same 50 works over and over. From 2004 to when the orchestra disbanded , due to much less financial support, in 2012, its conductors were Michael Christie and Alan Piersen whose work I am unfamiliar with.

Edwards was not a great writer but he was thorough in his documentation of programs, the ups and downs of its history, and the almost ad nauseam quoting of media coverage. In conclusion the book depicted an important orchestra which contributed much to the appreciation of live classical music concerts among all age groups, not just those over 60.

Edwards was married to the wonderful Romanian poet Nina Cassian (1924-2014).

From RPT’S essay Kennebec Crystals

“Tramps, even, were coming. And all the black sheep of a hundred faraway pastures, beyond Maine, were swinging off the sides of freight cars in the chill gray of the morning. Drifters from far beyond New England.”