FOR YOUR HEALTH: Statistics show decline in cancer related deaths

/0 Comments/in For Your Health/by Website Editor FOR YOUR HEALTH

FOR YOUR HEALTH

The American Cancer Society has announced updated cancer statistics, facts and figures which show a decline in the cancer death rate in recent years.

The main takeaway is, the cancer death rate dropped 1.7 percent from 2014 to 2015, continuing a drop that began in 1991 and has reached 26 percent, resulting in nearly 2.4 million fewer cancer deaths during that time.

The data is reported in Cancer Statistics 2018, the American Cancer Society’s comprehensive annual report on cancer incidence, mortality, and survival. It is published in California: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians and is accompanied by its consumer version: Cancer Facts and Figures 2018.

The report estimates that there will be 1,735,350 new cancer cases and 609,640 cancer deaths in the United States in 2018*. The cancer death rate dropped 26 percent from its peak of 215.1 per 100,000 population in 1991 to 158.6 per 100,000 in 2015. A significant proportion of the drop is due to steady reductions in smoking and advances in early detection and treatment. The overall decline is driven by decreasing death rates for the four major cancer sites: Lung (declined 45 percent from 1990 to 2015 among men and 19 percent from 2002 to 2015 among women); female breast (down 39 percent from 1989 to 2015), prostate (down 52 percent from 1993 to 2015), and colorectal (down 52 percent from 1970 to 2015).

While the new report also finds that death rates were not statistically significantly different between whites and blacks in 13 states, a lack of racial disparity is not always indicative of progress. For example, cancer death rates in Kentucky and West Virginia were not statistically different by race, but are the highest of all states for whites.

Prostate, lung, and colorectal cancers account for 42 percent of all cases in men, with prostate cancer alone accounting for almost one in five new diagnoses.

For women, the three most common cancers are breast, lung, and colorectal, which collectively represent one-half of all cases; breast cancer alone accounts for 30 percent all new cancer diagnoses in women.

The lifetime probability of being diagnosed with cancer is slightly higher for men (39.7 percent) than for women (37.6 percent). Adult height has been estimated to account for one-third of the difference.

Liver cancer incidence continues to increase rapidly in women, but appears to be plateauing in men. The long-term, rapid rise in melanoma incidence appears to be slowing, particularly among younger age groups. Incidence rates for thyroid cancer also may have begun to stabilize in recent years, particularly among whites, in the wake of changes in clinical practice guidelines.

The decline in cancer mortality, which is larger in men (32 percent since 1990) than in women (23 percent since 1991), translates to approximately 2,378,600 fewer cancer deaths (1,639,100 in men and 739,500 in women) than what would have occurred if peak rates had persisted.

“This new report reiterates where cancer control efforts have worked, particularly the impact of tobacco control,” said Otis W. Brawley, M.D., chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society. “A decline in consumption of cigarettes is credited with being the most important factor in the drop in cancer death rates. Strikingly though, tobacco remains by far the leading cause of cancer deaths today, responsible for nearly three in ten cancer deaths.”

*Estimated cases and deaths should not be compared year-to-year identify trends.

SCORES & OUTDOORS: Was it a Sharp-shinned hawk or a Cooper’s hawk? Hard to tell

/1 Comment/in Scores & Outdoors/by Roland D. Hallee

Sharp-shinned hawk, left, and Cooper’s hawk, right. Note the square tail of the Sharp-shinned hawk, compared to the rounded tail of the Cooper’s hawk.

SCORES & OUTDOORS

SCORES & OUTDOORS

by Roland D. Hallee

I have seen some interesting acts of Mother Nature during my travels, but what happened last week probably tops most of them.

The first was somewhat insignificant because I had seen it one time before. Arriving home from work late last Wednesday, I noticed a dead crow in my backyard. Not knowing quite what to do, I called the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife and was told it was OK for me to dispose of the bird. I feared that because they were vulnerable to West Nile disease, I should report it. I wasn’t sure I should touch it.

But what I saw on Saturday, topped that without a contest. After picking up my granddaughter at a basketball game to take her home (they live in a condo village in Waterville), I turned around in my daughter’s driveway. In front of her garage, I noticed a rather large bird obviously plucking the feathers of the prey it had taken down. Upon closer inspection, I saw that the unfortunate fowl was a male mallard duck.

The hunter was a rather smallish hawk that sat there almost motionless once it spotted me. It began to look uncomfortable with my presence, and flew into a nearby tree. I made a mental picture of the raptor and would try to identify it. Immediately, I ruled out broad winged hawk and redtail hawk, both of which I am familiar.

My research indicated to me that it was either a Sharp-shinned hawk, or a Cooper’s hawk. They had similarities that I couldn’t quiet determine which was which.

Sharp-shinned hawks are small, long-tailed (this one had a long tail) hawks with short rounded wings. Again, a match. Adults are slaty blue-gray above, with narrow, horizontal red-orange bars on the breast. Again, that was what it had. However, Sharp-shinned hawks breed in deep forests. This was in the center of Waterville.

The Sharp-shinned hawk is a woodland raptor, skilled at capturing birds on the wing. Its short, rounded wings permit it to snake through brushy areas. Its long, narrow tail serves as a rudder. They will surprise their prey with their speed, and prefer the ease of taking down birds weakened by disease or injury.

Now, the Cooper’s hawk resembles the Sharp-shinned hawk so much that even experts are often fooled. That didn’t leave me with a warm, fuzzy feeling about identifying the right culprit.

The Cooper’s hawk, however, has one real distinction: it is larger, more powerful, and able to kill larger prey. This particular hawk had taken down a mallard duck. Not quite the size of a chickadee which the Sharp-shinned hawk would prefer.

For decades during the 19th century, Cooper’s hawks were referred to as “chicken hawks” for their preference to taking chickens from backyards. So, for many years, they were hunted and slaughtered by the thousands. Fortunately, people came to understand the role that predators play in nature, and hawks are now protected by federal law. But, the Cooper’s hawk is its own worse enemy. They are woodland birds, so when they see a window, they see whatever the glass reflects, be it sky or trees. They think they can just fly through it. Sadly, they sometimes even succeed, but the price of success is still a broken neck.

Cooper’s hawks tend to be more common in suburban areas, where Sharp-shinned hawks nest in conifers and heavily wooded areas. The Cooper’s hawk has a rounded tail, that when folded, the outer feathers are shorter than the inner ones. The Sharp-shinned hawk’s tail is square, and both species have broad dark bands across their long tails. The hawk I saw had those bars.

So, what did I see. I’m going to have to say it was a Cooper’s hawk only because of the tail. The bird I saw had a tail that had shorter tail feathers on the outside and longer ones inside. That was probably the only thing I noticed that was significant. It was definitely the tail of the Cooper’s hawk. So, I guess I’m going to have to go with that.

Roland’s trivia question of the week:

Name the four NFL teams that have never made a Super Bowl appearance.

I’m Just Curious: It’s that time again

/0 Comments/in I’m Just Curious/by Debbie Walkerby Debbie Walker

Happy New Year! Oh yeah, it is that time again. The time of year when we once again are reminded we are not perfect! The magazines developed for women are going to give us the answers to improve us, yet again!

The magazines I am looking at now do not have very much information geared towards men; in all fairness I don’t remember seeing any magazines for men. I’ll have to pay closer attention next week and really look over the magazine rack.

I have three magazines in front of me now. The covers are always a hoot to read as long as you have the right attitude; the one where you don’t take any of it seriously.

One magazine cover has you “Drop 10 pounds in seven days,” and that is shown just below the picture of “Cranberry mmmm.” Another magazine: “Food Lovers Secret to Suddenly Slim! Hint: You can find it at Dunkin’ Donuts!” (Something slimming at Dunkin’ Donuts, not the first place I would look). There are also several pictures of food, goodies, and calories galore! Then, of course, there is “Forever Young!”, and “Stress Enders!” Stress, why would any woman feel stress?

While yet another magazine we can lose 10 pounds in 48 hours, that magazine cover is promoting champagne cupcakes. On the same cover they tell you a tea that will reduce worrying, placed just above a Happy New Year and a bottle of champagne! Maybe that champagne might reduce the worrying better! And each magazine is full of recipes.

Although I dislike the magazine covers and the message of “you need to improve ….” There is usually some information I find useful.

For the time being none of us are ever going to be perfect, sorry, but true. If I actually got my weight where it “should” be I still have big feet with problems and I’d just have more flopping skin! We don’t all do well with champagne and wine. I think the magazines I have been looking at are sort of like “… in a perfect world….”

Truthfully, I think we look at certain magazines for information we need, such as the ones that give me useful tips. I pick up the magazines, go through them for the ideas I like and then I pass the magazines on to Mom or Patsy. Patsy says she is always curious about what I pulled out before she got it.

Well, we will have to put up with the information we don’t care about to get the info we do care about. As for improving me, I pick and choose.

I’m just curious what you will find useful from my rambling or some of the magazines this month. Let me know. I am at dwdaffy@yahoo.com. Thanks for reading and don’t forget, we are online! Bye!

REVIEW POTPOURRI: Singer: Elvis Presley; Movie: Gangster Story; Composer: Brahms

/0 Comments/in Review Potpourri/by Peter Cates REVIEW POTPOURRI

REVIEW POTPOURRI

by Peter Cates

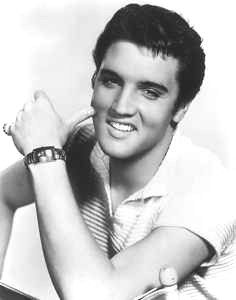

Elvis Presley

Loving You; Teddy Bear

RCA Victor 47-7000, seven-inch picture sleeve 45 rpm, recorded 1957.

Elvis Presley

Teddy Bear was a huge number one hit on the rock, country and rhythm and blues charts for the great Elvis (1935-1977). Both songs here were also part of the 1957 film, with the same name, and its soundtrack LP, consisting totally of Presley performances. Teddy Bear’s lyricist Bernie Lowe (1917-2001) was also a businessman who established Cameo records in 1956, which later expanded to Cameo/Parkway. He would sign an unknown singer, Ernest Evans, to the label, who himself later changed his name to Chubby Checker!

Both are superb songs, performed in a first rate manner.

Gangster Story

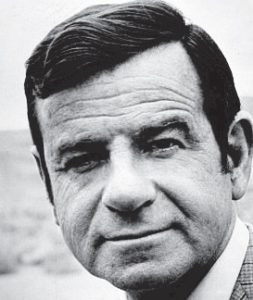

directed by and starring Walter Matthau and Carol Grace; 68 minutes; released December, 1959.

Walter Matthau

Carol Grace

Walter Matthau portrays a bank robber, Jack Martin, fleeing the police and needing cash. He then pulls a cleverly staged heist of a local bank in the town where he is hiding out, lays low at the library and becomes involved with a librarian, Carol Logan, played by his real life wife, Carol Grace; in fact, the couple married during the production of this film.

The main conflict is not only hiding from the cops but also from the local crime boss who wants a share of the loot.

I liked Matthau’s skilled acting, and directing, along with the shaping and development of the story. The obviously low budget cinematography brought out its own ‘50s small town ambiance – especially the beachside romance .

There are two delightful moments. When Jack is first scoping out the library, he asks Carol the rules. “No talking!” When sparks begin flying during their oceanside tryst, he asks again. “No talking!”

The DVD copy that I own was rather shabby but serviceable and part of an el cheapo three-movie package yet, despite these faults, the film was 68 minutes of captivating escapism.

Brahms

Symphony No. 2

Bruno Walter conducting the New York Philharmonic; Columbia, ML 5125, 12-inch mono LP, recorded December 28, 1953.

As I get older, I find it impossible to pick my favorite of the four Brahms Symphonies. They are all magnificent creations, each with a distinct quality that contributes to the number of times I listen to them again (not to mention the number of different recordings I own and to which I add).

Unlike the 1st Symphony which took ten years of effort before its 1876 premiere, the 2nd Symphony took final shape during a summer lakeside vacation a year later. The music is serene and comforting overall, although it too has its darker and more melancholy moments.

Bruno Walter (1876-1962) recorded it twice, the remake in stereo with members of the Los Angeles Philharmonic and free lancers grouped together as the Columbia Symphony and released during the very early ‘60s. It was a poetic approach but lacking a bit too much in muscle and bite.

This week’s record is a different matter. Walter not only communicated the singing qualities throughout but brought to life the lights and shadows of the orchestration that was a major part of Brahms’s genius.He would also impose tempos that might seem too fast but worked in helping the music to sing even more beautifully.

And, despite the New York Philharmonic’s fearsome reputation for chewing up conductors they didn’t like with bad playing and snarky attitudes, they responded totally to Walter’s conducting with their best.

Recommended totally!

IF WALLS COULD TALK, Week of January 11, 2018

/0 Comments/in If Walls Could Talk/by Katie Ouiletteby Katie Ouilette

WALLS, you and our faithful readers haven’t had me to read for awhile, so, first I must say Happy 2018 to all my friends at The Town Line and to the friends I haven’t met yet!

Frankly, WALLS, you know fell well that conversations and subjects can change and change they did when Lew came home with the mail and there was Dr. Victoria Stenmard pictured on the front page of Redington-Fairview General Hospital’s Newsletter. You know that I have much to be thankful for to Dr. Stennard, the RFGH staff and the ambulance staff that braved our driveway on Lake Wesserunsett, in East Madison, to get me to RFGH. About a month later, I was to praise Dr. Henry and her expertise as a surgeon. Maybe this is the time to thank RFGH President “Dick” Willette for his expertise in guaranteeing such great expertise as Dr.Stemmard and Dr. Henry even extend to their follow-up after the surgery.

pileated woodpeckers (wikimedia commons)

Hmm, must call attention to our monthly National Geographic magazine which arrived recently. On the cover was the feature inside entitled The Importance of Birds. That publication made me aware of birds that even come to our feeder all year long. Yes, we’ve had everything from pileated woodpeckers to, now, Snow Birds….and we surely have the snow for them now! Y’know, I wrote a book entitled Two Birds in a Box, which is a true-to-the-word story, but the publishers in New York City that I was encouraged to send it to wrote back that the book was too unbelievable to be true! Well, the folks who had Polar Bear Publishing in Solon, Maine, believed and not only is it dedicated to Landon, our great-grandson, but the dedication reads:

“To Landon and all the children in hospitals who are waiting for their time fly.” Landon is well, thanks to the people at St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital who got rid of his Wilm’s Cancer in the seven years that he was at the hospital in Memphis, Tennessee. He had his 20th birthday in December and is a student at Culinary Arts College, in Oregon. Yes, WALLS, we are happy, too.

SOLON & BEYOND, Week of January 11, 2018

/0 Comments/in Solon & Beyond/by Website Editor by Marilyn Rogers-Bull & Percy

by Marilyn Rogers-Bull & Percy

grams29@tds.net

Solon, Maine 04979

Good morning, dear friends. Don’t worry, be happy!

Some of this week’s news will be rather old because of the holidays and the fact that The Town Line wasn’t published on the week of Christmas. I find the news from Solon Elementary School very interesting so I try to get as much of it in this column as possible, but it is a little bit late. During the first two weeks of November, the Solon Kids Care Club ran their annual Thanksgiving Food Drive to collect food items for the Solon Thrift Shop Food Cupboard. They collected 163 items for needy families. The club thanks students and parents for their donations to this worthy cause.

A Jellybean Contest was held at Solon Elementary School during the month of November to see which student and staff member could come the closest to guessing the actual number of jelly beans in a jar. The student who guessed the number closest to the actual number of jellybeans in the jar (888) was fifth grader Tyler Ames. The staff member who came the closest was Ms. Gleason. Each of them won a Thanksgiving goodie bag.

In December Mr. Corson held a Parent Math Night for the parents of his fifth grade students. He reviewed with parents some of the math concepts he is teaching his students so that they can help their children at home. He also showed them some math tricks and shortcuts that the students are learning.

Solon’s annual town meeting will be held on Saturday, March 3, this year and those who have turned in nomination papers by the deadline of January 3 with the required number of names are Gaye Erskine and Keith Galleger for the selectman position; Gary Bishop for Road Commissioner, Leslie A. Giroux for Town Clerk/Tax Collector and Robert Lindblom Sr. for RSU #74 School Board member.

The annual budget committee meeting will be held on Saturday, January 20, at 8 a.m., at the Town Office Conference Room. Anyone interested besides budget committee members may attend, but only to listen.

Received the following e-mail from the trustees of Somerset Woods. The trustees are excited to announce a new gift of land in Concord Township of 204 acres from Norcross Wildlife Foundation of New York City and Massachusetts. The property was conveyed with the perpetual restriction that the land is to be maintained as a wildlife preserve.

Norcross had received the land from James R. and Diana C. Young in 2000. The Young family has owned the land for about 100 years, having been given to Jim’s parents as a wedding present by his father’s grandfather in 1916 or 1917.

The land contains the headwaters for Martin’s Stream which flows into the Kennebec River. There is an old beaver pond on the property and trails throughout. SWT will be managing the property to provide exemplary habitat for wildlife and trails for passive recreation. In the upcoming spring of 2018 SWT will be organizing a volunteer trail improvement day for anyone interested in trimming trails and enjoying the peaceful solitude that this property provides.

And now for Percy’s memoir entitled Charity:

Do something today to bring gladness,

To someone whose pleasures are few,

Do something to drive off sadness –

Or cause someone’s dream to come true.

Find time for a neighborly greeting

And time to delight an old friend;

Remember, – the years are fleeting

And life’s latest day will soon end!

Do something today that tomorrow

Will prove to be really worth while;

Help someone to conquer sorrow

And greet the new dawn with a smile –

For only through kindness and giving

Of service and friendship and cheer,

We learn the pure joy of living

And find heaver’s happiness here.

(words taken from a little book called, “Lift Up Your Heart.”)

GARDEN WORKS: Bored in Wintertime? Read on for the remedy

/0 Comments/in Garden Works/by Emily Cates

Winter is upon us!

GARDEN WORKS

GARDEN WORKS

by Emily Cates

For a while there, I’d thought Old Man Winter had forgotten us. No such luck! Now that we’re basking in the ice and snow, at least we can be comforted by the thought that the Solstice is behind us and the days will now start to get longer. Would it be a good time to take a respite from garden activities? Perhaps. But what if we’re feeling restless and would rather enjoy the satisfaction from getting things done? Well, then, read on for a few seasonally-appropriate suggestions; this time we’ll focus on a variety of activities, including pruning and tool maintenance.

First of all, though, let’s not forget to mark any trees or shrubs that might get smooshed by the snow plow. Are there specimens that need winter protection? Labels are often lost in the wind and snow, so making a map of ‘what’s there and where’ is always a good idea.

Black-knot fungus

Do you have European plum trees? Now is a fine time to check them for the fungal disease black knot. I have a Stanley plum that gets this every now and then. Trees with this problem will greatly appreciate our attention to this matter. Can we blame them? Black knot literally looks like dried dog poop on a branch, and will eventually spread to other branches if ignored. I’ve found it easier to spot against a backdrop of snowy ground. Prune off and burn or dispose of infected branches, and be sure to disinfect the pruners afterwards.

Speaking of pruning, we can remove dead, diseased, or damaged branches on any trees or shrubs any time of the year. What better time than now?

And when we’re done with our tools, why not clean, oil, and sharpen them so they’ll be in good working order? Uh-oh, is the tool shed a mess? Well, there’s another job for the ‘To Do List’! See how one project can lead to another? Now, that’s an antidote for boredom!

TRAINING YOUR DOG: Obedience – the foundation of all we do with our dogs

/0 Comments/in Training Your Dog/by Carolyn Fuhrer

TRAINING YOUR DOG

TRAINING YOUR DOG

by Carolyn Fuhrer

AKC defines its obedience program as trials set up to demonstrate the dog’s ability to follow specified routines in the obedience ring to emphasize the usefulness of the dog as a companion to humans; and it is essential that the dog demonstrate willingness and enjoyment while it is working, and that handling be smooth and natural without harsh commands.

In other words – the dog and handler enjoy working together. If you have ever seen beautiful heeling, you understand the wonderful flow of energy between the dog and handler. If you have ever seen bright, crisp signals and recalls, then you understand the focus and understanding between the team that comes from the heart.

Obedience is the foundation that enables our dogs to do all the wonderful things they do with us and for us. Obedience enables our dogs to be search and rescue dogs, herding dogs, therapy dogs, assistance dogs, agility dogs, freestyle dogs, and on and on.

Without obedience as a foundation, dogs could not participate in these activities. They need to be able to ignore distractions, make good choices, work under pressure, follow directions and have focus and attention. This is what obedience teaches and this is not a bad thing. All pet dogs could use these skills – it could even save their lives at some point.

There seems to be some feeling that commands are bad. Actually, in reality we give our dogs commands all the time, such as “wait” when we open the door to let them out; “sit and wait” when we go to put their food bowls down; “come” when we need them to join us. Whether you want to call them cues, requests or signals, is a question of semantics. We still expect some compliance and good manners when we ask something of our pets. This is not bad. Correction seems to be another difficult term – correction is simply a way of showing how something should be done. It does not imply pain or harshness mentally or physically. To anyone who has a poor opinion of obedience my guess is that they have never attended a good obedience class.

In a good class there is fun, excitement, laughter, challenges and lots and lots of rewards in many shapes and forms. Dogs are never – and I repeat – never corrected in any way for something they do not understand. This would be self-defeating for all involved. How could we create a willing, joyful, trustful partner if this was a method we employed? Are there poor obedience teachers out there? I’m sure there are, just as there are bad doctors and poor attorneys.

Positive training is not an entity in and of itself, but simply a way to teach obedience. Positive training and obedience training should not be an antithesis. Positive methods are employed to teach dogs obedience and life skills, and most successful obedience instructors use positive methods. There are also people out there claiming to use only positive methods and are not very good at it because they do not understand how to teach.

Even improper use of “clicker training” can cause terrible mental stress to a dog that is overwhelmed by the improper criteria.

So, let’s hope 2018 will be a year to bring more mutual respect to all those in the dog world and for how we choose to spend quality time with our dogs. We all basically share the same goals to enjoy living with our dogs and enjoy special activities with them.

A dog with an obedience foundation is a joy to live with and actually gets a lot more freedom than an uncontrolled dog. It is irresponsible to allow an uncontrolled dog total freedom. All dogs need an obedience foundation.

I am very proud of all of my students and the relationship they have developed and built upon through obedience. Not sure? Find a good obedience class to watch and talk with the students and learn how much it could do for you and your dog.

Carolyn Fuhrer has earned over 100 AKC titles with her Golden Retrievers, including 2 Champion Tracker titles. Carolyn is the owner of North Star Dog Training School in Somerville, Maine. She has been teaching people to understand their dogs for over 25 years. You can contact her with questions, suggestions and ideas for her column by e-mailing carolyn@dogsatnorthstar.com.

Give Us Your Best Shot! week of January 4, 2018

/0 Comments/in Give Us Your Best Shot!/by Website EditorInteresting links

Here are some interesting links for you! Enjoy your stay :)Site Map

- Issue for April 3, 2025

- Issue for March 27, 2025

- Issue for March 20, 2025

- Issue for March 13, 2025

- Issue for March 6, 2025

- Issue for February 27, 2025

- Issue for February 20, 2025

- Issue for February 13, 2025

- Issue for February 6, 2025

- Issue for January 30, 2025

- Issue for January 23, 2025

- Issue for January 16, 2025

- Issue for January 9, 2025

- Issue for January 2, 2025

- Issue for December 19, 2024

- Issue for December 12, 2024

- Issue for December 5, 2024

- Issue for November 28, 2024

- Issue for November 21, 2024

- Issue for November 14, 2024

- Issue for November 7, 2024

- Issue for October 31, 2024

- Issue for October 24, 2024

- Issue for October 17, 2024

- Issue for October 10, 2024

- Issue for October 3, 2024

- Sections

- Our Town’s Services

- Classifieds

- About Us

- Original Columnists

- Community Commentary

- The Best View

- Eric’s Tech Talk

- The Frugal Mainer

- Garden Works

- Give Us Your Best Shot!

- Growing Your Business

- INside the OUTside

- I’m Just Curious

- Maine Memories

- Mary Grow’s community reporting

- Messing About in the Maine Woods

- The Money Minute

- Pages in Time

- Review Potpourri

- Scores & Outdoors

- Small Space Gardening

- Student Writers’ Program

- Solon & Beyond

- Tim’s Tunes

- Veterans Corner

- Donate