REVIEW POTPOURRI: Masterpieces of Eloquence

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Masterpieces of Eloquence

A 1905 twenty five volume set, Masterpieces of Eloquence, contains a May, 1812, speech from Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) which conveys a certain megalomaniacal arrogance as his armies were rampaging Central and Eastern Europe already on their way to Moscow:

“Soldiers, – The second war of Poland has begun. The first war terminated at Friedland and Tilsit. At Tilsit Russia swore eternal alliance with France and war with England. She has openly violated her oath, and refuses to offer any explanation of her strange conduct till the French Eagle shall have passed the Rhine and consequently shall have left her allies at her discretion. Russia is impelled onward by fatality. Her destiny is about to be accomplished. Does she believe that we have degenerated? that we are no longer the soldiers of Austerlitz? She has placed us between dishonor and war. The choice cannot for an instant be doubtful.

“Let us march forward, then, and, crossing the Niemen, carry the war into her territories. The second war of Poland will be to the French army as glorious as the first. But our next peace must carry with it its own guarantee and put an end to that arrogant influence which for the last fifty years Russia has exercised over the affairs of Europe.”

As with dictators in later years, Napoleon truly believed he would experience greater glory and power and invoked such words as “destiny, dishonor, peace”; but within less than two years before the Corsican’s defeat at Waterloo, his armies would begin reckoning with some setbacks, a major one the Russian winter in which its temperatures would make those of Maine seem like ones in the Bahamas.

The place names mentioned in Bonaparte’s speech are in the Austrian/Eastern Europe region.

The Masterpieces of Eloquence also contains speeches from such an array of orators as Rene Chateaubriand, John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson and De Witt Clinton.

Beethoven Sonatas

Beethoven Sonatas 13 and 20; Rondos #1 and 2, Rage Over a Lost Penny; and Variations on the Turkish March. Hugo Steurer, pianist; Urania URLP 7033, LP, recorded 1952.

Pianist Hugo Steurer (1914-2004) was more well known as a teacher in Germany and later in England and left very few recordings. This one of Beethoven piano music reveals an artist who played with a natural understated quality, avoiding the slam bang theatrics of certain keyboard superstars. And these early 50s performances can be heard on YouTube.

Beethoven 9 Symphonies; Overtures- Fidelio, Leonore #3, Egmont, Coriolan, Creatures of Prometheus, Nameday, King Stephen, and Consecration of the House; 12 German Dances; and Wellington’s Victory. Kazuyoshi Akiyama conducting the Hiroshima Orchestra, Tobu TBRCD 0113-0118, six compact discs, 2001-2003 live performances.

Maestro Kazuyoshi Akiyama (1941-2025) conducted the Vancouver Symphony, the Albany Symphony and New York City’s American Symphony for several years beginning in the 1990s and did outstanding work with Japanese orchestras during a career lasting well over 60 years until he suffered a fall at home in late January, 2025, and died a few days later.

Beethoven’s 9 Symphonies abound in very good performances, proving their unfathomable depths of beauty; Akiyama conducted them with rhythmic excitement, grace and elegance and held his own against the cycles of Toscanini, Walter, Jochum, Karajan and, more recently, Van Zweden and Sir Simon Rattle. The Overtures, German Dances and the showpiece Wellington’s Victory were delivered with flair.

Tobu and Weitblick are Japanese CD labels that have made available various broadcasts from the past featuring Carlo Maria Giulini, Yevgeny Svetlanov, Georges Pretre, Kurt Sanderling and others no longer with us conducting orchestras in Europe and Japan, a number of which I own. And the quality of music making and recorded sound is consistently high. So often conductors and orchestras prefer a live audience over the cold studios to achieve excitement.

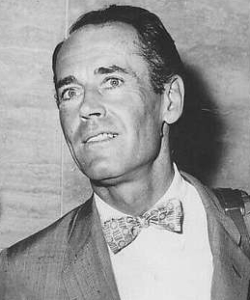

Jill Corey

Jill Corey – Exactly Like You; I Told a Lie to My Darlin’. Columbia 4-41068, seven inch 45, recorded 1957.

Pop vocalist Jill Corey (1935-2021) was a regular on 1950s Your Hit Parade and a comedy variety show Johnny Carson hosted on local TV in Los Angeles.

She had a feisty in your face style of enthusiasm and each of the two above selections are examples of corny novelty pop songs of the mid-1950s with skilled arrangements from Columbia’s Jimmy Carroll who worked with Mitch Miller in numerous sessions there and at Golden Records; and from Ray Ellis who scored some of Johnny Mathis’s greatest hits – Chances Are, Twelth of Never, Small World, A Certain Smile, etc.

Corny pop songs, and me being sometimes in a 1950s time warp of my childhood, very enjoyable corny pop songs.

In 1963, the gifted singer Andy Williams included Exactly Like You on his very highly recommended Days of Wine and Roses album where I first heard it in seventh grade.