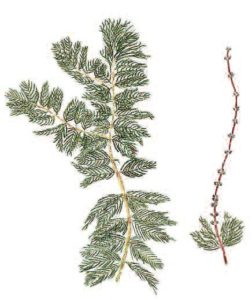

A “field” of weeds in the northwestern corner of Webber Pond. Photo courtesy of Frank Richards, president of Webber Pond Association.

At their August 18 annual meeting, held at the Vassalboro Community School, members of the Webber Pond Association heard about various matters of interest, including water levels and clarity, bacterial infections, increasing the alewife harvest, changing the annual meeting date, and finally, a presentation on ways to deal with the increased amount of weeds in Webber Pond.

There was concern about the water level in the pond, which drew considerable dialogue. As of August 18, the water level in the pond was four inches below the spillway following the heavy rains of the previous two days. Prior to that the water level had been measured at six inches below the spillway by association president Frank Richards. Phil Innes, who monitors the dam, reported at the meeting the levels had risen. He had taken the latest reading the morning of the meeting. It is recommended the level be set at one to two inches below the spillway by the Maine Department of Environmental Protection.

All the boards are in the dam except for one which must be left open to allow the egress of mature alewives, who otherwise would have no way to exit the pond. Doing so allows more water to escape the lake than would be ideal. Failure to allow the mature alewives to leave the pond could possibly result in around 100,000 alewives trapped in the lake, eventually dying, creating even more problems in the lake, according to Vice President Charles Backenstose.

Richards mentioned conversations with the state that a specially-engineered egress channel could possibly be installed that would allow the fish to continue to exit the pond, but by releasing much less water. This method is now being used in new fish ladder construction, and has proven to be successful, according to Richards.

Backenstose, who monitors water clarity in the lake through Secchi Disk readings, reported that water clarity was typical from mid-May through late June at 14 – 15 feet. “This is pretty amazing, considering that last year at this time, visibility was about half that,” he reported in the group’s newsletter. “The dry weather may have contributed to clearer water.”

Although, at the meeting, Backenstose reported that as of the week of August 12, water clarity had diminished to about six feet.

Answering a concern about incidents of bacterial infections reported in the local newspapers at other central Maine lakes, Director Susan Traylor reported that Webber Pond has never appeared on the list of lakes where these types of bacteria, including e-coli, have been identified.

Traylor also made a presentation about the possibility of increasing the alewife harvest. In her research, she concluded the lake association should recommend to the town of Vassalboro that the town submit a revised alewife harvest plan to the Maine Department of Marine Resources for the 2019 season that would allow a change to the current harvest plan, which has been in place for over a decade. She concluded that no more than 240,000 alewives should be allowed to enter the pond.

In an article in the newsletter, Traylor states the 240,000 target allows for 100 alewives per acre in both Webber and Three Mile ponds. In 2018, 461,000 alewives entered Webber Pond. Of these, an estimated 38,000 went to Three Mile Pond (about 33 per acre). This left 423,000 (352 alewives per acre) in Webber.

This study came as a result of the issue having been raised at the 2017 annual meeting that maybe there were now too many alewives entering the lake, possibly creating an imbalance in nutrients being brought into the lake as opposed to what is removed with the fall egress of the young alewives.

Two options were presented to the membership by Traylor. Richards suggested the body give the president permission to use option #1 in his negotiations with the DMR. That option states: [The lake association] recommends that the town of Vassalboro submit a plan to DMR to harvest seven days a week once a target number of 240,000 alewives have entered Webber, with no further alewife entry to the pond. In 2018, following this practice with a target of 240,000 alewives would have allowed the boards in the dam to be replaced on May 30, rather than June 16.

Presently, the plan calls for alewife passage for three days a week and allows alewife harvesting the other four days. There is no limit on the number of alewives that can enter the pond.

Replacing the boards at the dam on the latter date in 2018 contributed, to some degree, to the lower water levels in early summer.

Jim Hart, director of the China Region Lakes Alliance (CRLA), warned against acting too quickly. In his address, he stated that alewives return to their place of birth. Therefore, alewives that are leaving Three Mile Pond, and returning to the ocean to mature, will be back in four years. They will most likely return to Three Mile Pond, and not stay in Webber Pond. That could affect the number of alewives that remain in Webber Pond, and vice versa. He suggested a three- to four-year trial period.

The motion to recommend increasing alewife harvest was the only item on the agenda that caused lengthy discussion, with the final straw vote being 17-8 in favor of the increase. The DMR has final say on the matter.

The final item on the agenda was a presentation by Nick Jose, a Vassalboro resident who is a third-generation resident of Webber Pond. He had seen a video on YouTube describing a piece of equipment that would literally mow the weeds on the pond.

The machinery would cut the weeds two feet down from the water surface, gathered into hoppers, brought to shore and loaded into trucks by conveyor belt, to be hauled away to a composting facility. Presently, he states, weeds are being cut by boat propellers and float to the surface. The wind carries the weeds to various locations on the lake, where they eventually sink, decay and begin the reseeding process that multiplies the weed infestation.

The equipment, which he said he was willing to invest in, carries a price tag of $200,000. Negotiations would have to take place to find a way to fund this project on both Webber and Three Mile ponds. He estimated the process would probably have to be repeated twice a year. He also stated the practice is ongoing throughout the country, and that DMR would be receptive to this program as long as the lake association was on board.

The question of whether there is milfoil present was answered by Richards, stating the weeds in the pond are native aquatic vegetation.

In other business, officers were elected: Frank Richards, president; Charles Backenstose, vice president; Rebecca Lamey, secretary; John Reuthe, treasurer.

Directors elected were returning directors Robert Bryson, Scott Buchert, Mary Bussell, Darryl Federchak, Roland Hallee, Phil Innes, Jennifer Lacombe, Robert Nadeau, Stephen Pendley, John Reuthe, Susan Traylor and James Webb. Pearley LaChance was named as a new director.

The annual drawdown of the pond, which historically has been a contentious subject, was set for Monday, September 17, at 8 a.m., by a unanimous vote of the membership.

Richards posed a question to the membership on the possibility of changing the date of the annual meeting to earlier in the summer. The straw vote showed the majority present preferred retaining the current date of the third Saturday in August.

Richards’ annual question as to whether anyone has caught, or heard of someone catching, a northern pike in Webber Pond was met with no response from those present.

The association also voted to contribute $1,500 to the CRLA.

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee

by Roland D. Hallee