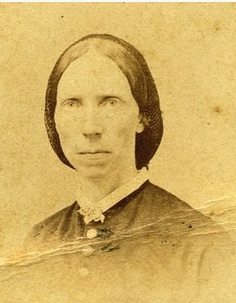

Up and Down the Kennebec Valley: Amy Morris Bradley

by Mary Grow

In her Vassalboro history, Alma Pierce Robbins introduced her readers to one of the town’s nationally-known residents, Amy Morris Bradley. Robbins’ focus was on Bradley’s role in nursing during the Civil War; other sources add information about her career in public education.

Bradley was born in East Vassalboro on Sept. 12, 1823, daughter of a cobbler named Abiud (or Abired) Bradley I (1773 – January, or June 11, 1858) and Jane Baxter Bradley (Aug. 27, 1779 – June 23, 1830) and granddaughter of Revolutionary War veteran Asa Bradley (1746 – 1780).

Find a Grave lists her as the youngest of four boys and two girls; her oldest brother, Asa, was 22 years older than she. The older children were born in Yarmouth, Massachusetts, on Cape Cod. Only the last two, Albert Morris (1818 -1897) and Amy Morris, were born in Vassalboro.

(Your writer found no explanation for “Morris” as the middle name of the last two Bradley children.)

The Find a Grave page says of Bradley:

“She was an exceptional child, wanting to learn and was always asking questions. The more she grew and the more she learn [sic] about society, she felt that women were not getting treated fairly in America.”

A history of American women found on line offers a similar comment, saying that Bradley “abhorred the limitations placed on women in the 19th century.”

An on-line encyclopedia adds that Bradley was “a frail child given to bronchial attacks.”

Bradley’s mother died when Bradley was six years old. The on-line encyclopedia says she lived with older married sisters until she was 15.

Robbins’ information on Bradley’s early life came from books on Maine women and women in the Civil War. By the time she was 16, Robbins found, Bradley was teaching school while she attended Vassalboro Academy, “working in private families for her board.”

(Vassalboro Academy was the town’s first high school, founded in 1835 at Getchell’s Corner.)

When she was 21, Bradley was principal of an academy in Gardiner. In 1846 or 1847, she was in Charlestown, Massachusetts, either teaching in Winthrop grammar school, principal of a grammar school or head of an academy (sources differ).

In the fall of 1849, pneumonia, tuberculosis or bronchitis (sources differ) sent her first to a brother’s home in South Carolina and then back to Maine in 1851 and 1852. Her Maine doctor recommended a warmer climate.

Robbins said a cousin who had three foreign students living with him suggested Costa Rica, and in 1853 (Wikipedia’s date) she moved to San Jose, the inland capital city of the Central American country. She promptly opened “the first English school in central America” where she taught until the summer of 1857.

That summer she came back to Maine to be with her ailing father, who died in January 1858 (Wikipedia; Find a Grave gives the June 11 date cited above).

Wikipedia says someone at the New England Glass Company, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who needed letters translated from Spanish, somehow learned that a woman in East Vassalboro, Maine, was fluent in the language and hired her. Bradley was living in Cambridge when the Civil War started in April 1861.

After the first Battle of Bull Run in July, Wikipedia says, she volunteered as an army nurse. (How she qualified as a nurse, no source explains.)

Her obituary says her first assignment was the Third Maine Regiment hospital near Alexandria, Virginia. She soon transferred to the Fifth Maine Infantry. Robbins commented that many of those soldiers had been her students in Gardiner.

During the first winter of the war, her obituary says, she was matron of the 17th Brigade Hospital. She was again transferred – Robbins wrote on May 7, 1862 – to a hospital ship named “Ocean Queen,” on the James River in Virginia.

WikiTree says Bradley was the ship’s “lady superintendent,” overseeing 1,000 patients who were on their way to New York to recover, and their nurses. Bradley served on this and two other hospital ships until the summer of 1862.

Robbins said she took part in prisoner exchanges. She quoted from the Civil War book that Bradley’s kindness to Rebels “persuaded many to change their loyalty to the Union.”

From the ships, Bradley moved to a soldiers’ home in Washington, D.C., from which she began working for the United States Sanitary Commission.

Wikipedia explains the sanitary commission was “a private relief agency created by federal legislation on June 18, 1861, to support sick and wounded soldiers of the… Union Army.” It raised money, collected in-kind contributions and “enlisted thousands of volunteers” in the North, increasing the number and especially the quality of hospitals for soldiers.

Wikipedia lists most of the leaders of this group as men. Its article mentions a dozen women, including novelist Louisa May Alcott – but not including Bradley.

The on-line women’s history says Bradley became a Special Relief Agent for the Commission. “In that capacity she transformed makeshift army hospitals from unsanitary camps into clean, efficiently-run hospitals.” Other sources name some of the hospitals where she worked, and describe the deplorable conditions she corrected.

The history article says more than 20,000 women worked with the army in the Civil War. They were not well treated; the writer said they “had to deal with the intoxication of surgeons, the contempt of generals and the challenge of dealing with filth, lack of supplies, mosquitoes and bad weather.”

He or she added, “Bradley’s success earned her the respect of influential military and political leaders.”

On Feb. 16, 1864, Bradley began publishing the weekly Soldiers Journal, a collection of poetry (some of which she wrote), soldiers’ letters and military-related news. Publication continued until June 1865; President Abraham Lincoln was among the 20,000 subscribers. Profits from the journal went to soldiers’ orphaned children.

The Civil War ended with General Robert E. Lee’s surrender on April 9, 1865. That year, the women’s history says, Unitarians in Boston created the Soldiers’ Memorial Society, an organization to “establish free schools for poor children in the city of Wilmington, North Carolina.”

Bradley joined the Society and became its agent in Wilmington. She reached the city, by train, on Dec. 20, 1866. Not everyone welcomed her. The women’s history site said:

“Bradley soon became a familiar Wilmington figure as she went from house to house to drum up interest in her proposed school. Though some women pulled their skirts aside when she passed, or spat upon her, she held her head high and continued her rounds.”

It also quoted an article from the newspaper the Wilmington Dispatch that called Yankee teachers “obnoxious and pernicious.” The writer accused them of alienating Southern children from their roots and introducing the “puritanical schisms and isms of New England.”

Bradley was given the key to a disused schoolhouse, where she welcomed three students in January 1867. By spring, she wrote, “I have a day school of seventy-pupils thoroughly organized and classified; an industrial-school of thirty-three, and a Sunday school.”

Thirty-four “gentlemen of this city” gave almost $100 to her Union school. She used the money to buy books for every student and a “magnetic globe,” and for classroom improvements.

By the summer of 1867, Wilmington residents had contributed $1,000 to buy land for a second school, and two groups contributed a building fund and $1,500 for teachers’ salaries.

According to the on-line history, the Union school reopened early in November 1868 (presumably it also ran during the winter of 1867-1868), with 223 students and three teachers. The new Hemenway school (its name honored Mary Porter Tileston Hemenway, who had given $1,000 – see box) opened on Dec. 1, 1868, with 157 students. A third school under Bradley’s auspices, the Pioneer school in Masonboro Sound, opened on Jan. 1, 1869, with 45 students.

(Masonboro Sound is now a historic district near Wilmington, Wikipedia says.)

An on-line encyclopedia article says Bradley was made superintendent of Wilmington’s school system in 1869. In 1872, this source says, again with financial support from Mary Hemenway, Bradley “opened Tileston Normal School in Wilmington to train local women for teaching positions.”

Failing health led her to resign from the normal school in 1891. Wikipedia says the school closed that year.

Amy Morris Bradley died on Jan. 15, 1904, in “a little brown cottage on the school grounds,” and is buried in Wilmington’s Oakdale Cemetery.

WikiTree quotes from a 1904 letter by the then editor of the Wilmington Dispatch: “She was one of Wilmington’s foremost citizens, and the magnitude of her work stands out today as an everlasting monument. Miss Bradley was the mother of public school education in Wilmington.”

Her tombstone calls her “Our School Mother.”

Mary Porter Tileston Hemenway

Wikipedia calls Mary Porter Tileston Hemenway a philanthropist who “funded Civil War hospitals, numerous educational institutions from the Reconstruction era until the late 1880s, founded a physical education teacher training program for women, and funded research for the preservation of culturally valuable historical sites.”

She was born Dec. 20, 1820, daughter of a wealthy New York City “shipping merchant” and his wife. In 1840, she married Edward Augustus Holyoke Hemenway, a multi-millionaire “Boston sea merchant” 17 years her senior. They had four daughters and one son.

When her husband died in 1876, Wikipedia says his widow “apparently inherited $15,000,000.”

She had been giving away his money before then. Wikipedia credits her with contributions to the Sanitary Commission (perhaps her first connection with Amy Morris Bradley?); Washington University, founded in 1864 in St. Louis, Missouri; Bradley’s first two schools in Wilmington, and Bradley’s salary; the Tileston Normal School in Wilmington; and in 1868 the school in Hampton, Virginia, founded to teach literacy and job skills to former slaves, that became Hampton Institute and is now Hampton University.

After 1876, her gifts continued. Wikipedia says in 1885, “to help develop industrial skills for girls, Hemenway funded a two year training program for sewing and cooking classes in Boston. She financed the first kitchen in a public school in the United States, known as the Boston School Kitchen.”

This was followed in 1887 by “the Boston Normal School of Cookery…to train teachers. She bore all the expenses until the school was fully functioning before turning it over to the Boston School Committee.”

Two years later, Hemenway organized an international physical education conference at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology that led to adding exercise programs for Boston school children. The same year, she founded the Boston Normal School of Gymnastics, which trained women to teach the Swedish physical education system in schools, including colleges, “at a time when very few women had positions in higher education.”

Wikipedia says BNSG became part of Wellesley College in 1906, and Wellesley’s new gymnasium was named Mary Hemenway Hall. (A Wellesley website says the Hall was demolished in the 1980s and replaced by the Keohane Sports Center.)

Another area that benefited from Hemenway’s interest and donations was southwestern archaeology. Wikipedia says in the 1880s and 1890s she supported studies of Hopi and Zuni history, language and culture, and was instrumental in persuading Congress to protect the Hohokam Casa Grande ruins in Coolidge, Arizona, as a national monument (established by President Woodrow Wilson on Aug. 3, 1918).

Hemenway died March 6, 1894, at her home on Beacon Hill. Appropriately, her memorial service was held in Boston’s Old South Meeting House.

The building started as a Puritan meeting house in 1729. After its congregation moved elsewhere in 1872, it was sold and scheduled to be demolished, but a group of Boston women, including Hemenway, who donated $100,000, raised money to buy and preserve it. Since 1877, an on-line history says, it has been a public “museum and meeting place.”

Main sources

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971)

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!