Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Augusta families – Part 5

by Mary Grow

Henry Sewall, part two

Last week’s article on Henry Sewall (Oct. 24, 1752 – Sept. 4, 1845) omitted (or rather postponed) an important aspect of his life: he was a deeply religious man.

James North, in his history of Augusta, summarized: “He was upright, conscientious, pious and rigidly orthodox in his religious views. Towards the close of his life his religious rigor was much softened.”

Sewall’s diary is a main source for North’s history into the 1790s, and fellow Augusta historian Charles Nash excerpted it from 1830 to 1842. Sewall wrote where he went to church and who preached almost every Sunday, and there are frequent references to weekday services and religious organizations.

Especially in his earlier years, Sewall often had public disagreements with whatever minister the town hired.

In 1784, North wrote that the preaching of Rev. Nathaniel Merrill “was not acceptable to Capt. Henry Sewall, who soon discontinued his attendance.”

The next year, voters hired Rev. Seth Noble from September 1785 to mid-March 1786. Sewall disapproved of Noble’s doctrines, too, and joined other dissatisfied residents who gathered Sundays for worship at Benjamin Pettingill’s (sometimes Pettengill).

Despite having contracted with Noble, North wrote, when voters got a recommendation to hire Rev. William Hazlitt, they named Sewall, Cony and North as a committee to hire him for two months. On Nov. 13, Sewall heard his morning sermon, declared him an “Armenian” and probably an “Arian” and went to Pettingill’s for the afternoon.

(The Encyclopedia Britannica defines Arminianism as a Protestant doctrine that denied predestination and said the idea free will did not contradict belief in a sovereign God. The same source says Arianism “stresses God’s unity at the expense of the notion of the Trinity.”)

There were at least two ministers who did meet Sewall’s standards. In 1785, he once “went nineteen miles to Jones’ plantation” (later China) to hear a Rev. Kinsman (North gives no first name), who also preached in Hallowell, including at Thomas Sewall’s house (Thomas and Henry were brothers). That same year, Sewall praised Rev. Ezekiel Emerson when he came from Georgetown to preach in Hallowell.

In 1786, a 15-man committee including Sewall (and James Howard and Daniel Cony) recommended a salary for a new young minister named Isaac Foster, from Connecticut. Foster began preaching in July; North quoted from Sewall’s diary: “preached poor doctrine”; “preached rank Arminianism.”

In August, according to Sewall’s record, he met twice with Foster, but failed to “convince him of the impropriety of his doctrines.” As most of the rest of the townspeople prepared to ordain Foster their minister on Oct. 11, 1786, Sewall remained opposed, even preparing written objections to Foster’s beliefs.

A council of ministers approved Foster as Hallowell’s minister and a “public teacher,” after an all-day debate at Daniel Cony’s house. North surmised that Sewall skipped Foster’s sermons and went to Pettingill’s on Sundays, where he “probably officiated to the few who sympathized with him.”

At some point, Sewall called Foster a liar. As a result, he and his brother Thomas (who “was in some way connected with the charge,” North wrote) were brought to court, convicted and fined. Thomas Sewall paid his 12 shillings; Henry Sewall appealed his fine of “fifteen shillings and costs.”

He claimed to have proof of his accusation against Foster, but apparently the corroborating witness was unavailable when the appeal was heard in June 1787, and the higher court refused to allow a continuance (because the parties couldn’t agree on where it should be held). Lacking evidence, Sewall gave up and paid his fine – “wisely,” North commented.

Foster (who had been accumulating enemies and detractors) on May 9, 1788, sued both Sewalls. North said he demanded 500 pounds from each man.

The Sewalls sent a friend to Foster’s previous ministerial post to find evidence against him. Thomas Sewall again ducked out of the case, trusting a three-man committee to rule on his role.

Henry Sewall’s case was initially scheduled in June and postponed to January 1789. But in the fall of 1788, after long and acrimonious debates, Hallowell fired Foster, and apparently the case died.

After the Foster affair, North wrote, some Hallowell people got together with a group from Chester Plantation (now Chesterville, some 35 miles northwest of Augusta; Henry and Thomas Sewall’s brother Jotham lived there) and in 1790 formed the Chester Church. On March 15, 1791, these members met at Sewall’s house and renamed themselves “A Congregational Church of Christ in Hallowell.”

In June that year, Sewall found – met in a tavern on his way to visit another minister, North claimed – Rev. Adoniram Judson, who preached briefly in Hallowell to the “new” – Sewall’s – church but was spurned by all but one member of the “old” Hallowell church.

In the fall of 1792 the two Hallowell churches tried to merge, but agreed only to invite three outside ministers to help them. In mid-January 1793, the outsiders drafted a merger agreement.

But, North quoted (from Sewall’s diary, your writer suspects), the “new” church people (specifically, Henry Sewall, your writer suspects) “had weighty objections…to several members of the other church on account of doctrines and moral character.”

After a private session, the objectors agreed to the merger on condition that it could be undone at the request of a majority of either church. In June 1794, North wrote, after some former members of the “old” church had been disciplined “on account of doctrine and unbecoming conduct,” the former Chester church again became a separate entity. North did not name Sewall in describing the split, though he based his description on Sewall’s diary.

The original single congregational parish in Hallowell became three in 1795. When Augusta became a separate town in 1797, what had been Hallowell’s middle parish, with its 1795 meeting house, became Augusta’s south parish.

By the time your writer was able to pick up Henry Sewall’s story again at the beginning of 1830, he was regularly attending “Mr. Tappan’s church” (Rev. Benjamin Tappan) in the south parish, where a series of visiting ministers preached on Sundays. Sewall often attended more than one Sunday service, as well as weekday meetings.

From June 22 through June 24, 1830, he (and on June 23 and 24 his wife) were at the Maine Missionary Society’s general conference in Winthrop, with enough delegates from Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts and Kentucky to fill the meeting house.

From Sept. 14 through 16, the Sewalls were at the County Conference of Churches, where he was a delegate. The conference was in Chesterville, so he visited Jotham, but the Sewalls stayed with a non-relative who lived nearer the meeting-house.

In October 1830 he was gone for almost two weeks to Boston for the annual meeting of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. He went to Boston by steamboat from Portland; the ocean was rough when the meeting ended, so he came all the way home by stagecoach, via Portland and Brunswick.

Sewall went to another A.B.C.F.M. meeting in Portland in September 1838. His diary does not explain either time whether he was a delegate or an observer.

On May 4, 1831, Sewall noted that Tappan began a four-day meeting. Each day’s schedule had an hour of morning prayers at 5:30, prayer meetings and preaching at intervals all day and a 7 p.m. lecture that lasted up to two hours.

Sewall mentioned his personal opinions in two contexts: he opposed Masonry (the fraternal organization, not the building-trade skill he practiced), and he supported temperance.

He noted in his diary that on Jan. 7, 1830, he responded to a request for his “views of freemasonry.” On Jan. 28, he wrote, “My Renunciation of Freemasonry appeared in a Boston anti-Masonic paper.”

The July 29, 1831, publication of a new anti-Masonic newspaper in Hallowell was worth mention; and he sent to “Gen. Crosby” in Houlton a letter and “4 anti-masonic Almanacs.”

On July 4, 1832, Sewall noted the Anti-Masonic state convention at the “new courthouse,” whose members nominated candidates for governor and for U.S. president and vice-president. They attended Tappan’s church in the afternoon.

In mid-October, Sewall wrote about going to Wiscasset and after discussion with “Major Carlton,” advising the anti-Masons to join the National Republicans on a “union ticket” for presidential and vice-presidential electors, “provided there should be no adhering Masons thereon.”

Sewall sometimes attended temperance lectures, and on March 31, 1841, wrote in his diary, “A remarkable reformation among the intemperate here, and through the country in general. Hope and pray it may not prove a failure, as some other reforms have done.”

Less than a month later he recorded the formation of a Washington Temperance Society in Augusta by the local rum drinkers. By May 14, he wrote, 150 local men had pledged abstinence.

The inscription on Sewall’s tombstone in Augusta’s Mount Vernon Cemetery reads: “An officer in the Revolutionary War. Major General of Militia in Maine; yet more honorably known as a good soldier of Jesus Christ, and a faithful officer in the Christian Church.”

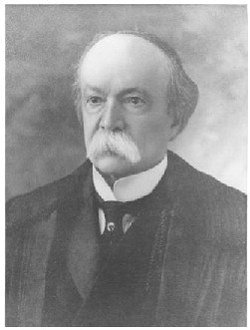

Rev. Benjamin Tappan

Rev. Benjamin Tappan, D.D. (Nov. 7, 1788 – Dec. 22, 1863), was pastor of Augusta’s South Congregational Church from 1811 to 1849.

A plaque in the church at 9 Church Street, Augusta, is dedicated “to the glory of God, and in memory of” Rev. Tappan. It reads: “His children here reverently record their undying gratitude and love for a Father in whom wisdom, integrity and a large-hearted benevolence were joined to steadfast faith in Christ, and untiring activity in His service.”

Tappan, son and grandson of Congregational ministers, was born in West Newbury, Massachusetts; graduated from Harvard College in 1805 (before his 17th birthday); taught in Massachusetts; and in 1809 became a tutor at Bowdoin College. He was later vice-president of Bowdoin’s board of trustees.

In October 1811 he was “ordained over” the Augusta church, where he stayed until 1849.

Adjectives North applied to Tappan include “active, industrious…zealous, devoted, benevolent, learned and pious…humble and accessible to the lowly.” An on-line biography describes him as “an immense worker,” “noted for his hospitality and generosity” and “an effective preacher…[with] a remarkable gift in prayer.”

In June 1814 Tappan married Elizabeth B. T. Winthrop, from a wealthy Boston family; they had seven children. North wrote that he gave so much to charity that by the time he died his wife’s fortune was reduced, but “she was as charitable as she was kind, and encouraged his giving.”

Tappan was an early supporter of the temperance movement; the biography says his first sermon on temperance was in 1813.

Henry Sewall noted in his diary that on Sunday, July 4, 1830, Tappan’s sermon was on slavery, and he “had a contribution in aid of the Colonization Society.”

(The American Colonization Society was founded in 1816 to help ex-slaves and other free blacks emigrate from the United States to Africa, especially to Liberia. Many African-Americans and many abolitionists opposed it. Its activity declined after the Civil War, but Wikipedia says it was not officially dissolved until 1964.)

While supporting colonization, Tappan appears to have been an abolitionist. Nash wrote that when the Maine Anti-Slavery Society was organized in Augusta in October 1834, Tappan hosted British abolitionist George Thompson.

Tappan left the Augusta church in 1849 to become secretary of the Maine Missionary Society, a position he held until his death.

The biography says his honorary Doctor of Divinity degrees came from Waterville College (now Colby College) in 1836 and from Bowdoin in 1845.

The church in which Tappan preached was not the present Gothic Revival building, but the second of three churches on the site, built in 1809 and struck by lightning and burned in 1864 (see the Nov. 10, 2022, issue of The Town Line).

Main sources:

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!