Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Livestock

by Mary Grow

Besides crops, the other major facet of agriculture is livestock. For early Kennebec Valley settlers, cattle, a term that includes milk-producers, meat-producers and draft animals, were especially important.

North Fairfield settler Elihu Bowerman, whose account of his early life was excerpted in the Fairfield Historical Society’s bicentennial history (and quoted in the March 18 issue of The Town Line), acquired two cows in the summer of 1784. The cows were turned loose, and Bowerman claimed “he ran hundreds of miles in the woods after cows, often without shoes.”

Vassalboro’s 1792 assessors’ report, excerpted in Alma Pierce Robbins’ history of the town, listed “96 cows, 114 oxen, 37 horses, 104 steers, and 124 swine.” The town also had a tannery and a slaughterhouse.

In his history of Windsor, Linwood Lowden wrote that the first cattle were heavy breeds like Durhams. Horses came into favor later, and so did milk cows, he wrote. Other local historians, including Alice Hammond in her history of Sidney, list milk cows and chickens as essential for an early farm family.

Milton Dowe, of Palermo, born in 1912, wrote both a 1954 history of his town and a booklet of reminiscences, Palermo, Maine: Things That I Remember in 1996. In the latter he observed, without giving a date, that teams of oxen, “strong but slow moving” were common. If an ox died, he pointed out, the meat was eaten – “This was different than losing a horse.”

Lowden cites one Windsor farmer who died in 1812 and another who died in 1813, each leaving one horse and one cow. A Windsor farmer who died in 1817 had two cows and a bull, two yearlings and a calf, four sheep, five pigs and two swine.

(Other sources use “pig” and “swine” interchangeably. Wikipedia says a pig is “any of several intelligent mammalian species of the genus sus, having cloven hooves, bristles and a nose adapted for digging”; and a swine [the word is both singular and plural] is “any of various omnivorous, even-toed ungulates of the family suidae.”)

Lowden surmises that the man who died in 1817 had owned at least one team of oxen, because his belongings included an ox yoke and ox-cart wheels. Also in the inventory was a pair of sheep shears.

Lowden could find no statistics on sheep in Windsor, but he assumed they were numerous, because before 1815 Owen Clark built a fulling mill on the West Branch of the Sheepscot River. It changed hands almost immediately, and ran “for many years.” There was apparently an associated carding mill or carding machine.

(Wikipedia explains that in a carding mill, wool fibers were brushed into alignment to make the wool into rolls for spinning or batting for quilts. In a fulling mill, wooden mallets powered by water pounded woolen fabric to make it thicker and more compact.)

Ruby Crosby Wiggin mentioned in her Albion history that William Chalmers, who had a gristmill on Fifteen Mile Stream by around 1800, “later is said to have built other mills including a carding mill.” Wiggin also found Jonah Crosby’s account book in which he recorded trades he made. Sometime in 1814 he loaned 10 sheep to Benjamin Webb for a year, expecting in return 10 pounds of wool.

Henry Kingsbury, in his Kennebec County history, listed three carding mills in Waterville, one in Sidney and a three-story-tall carding mill in East Vassalboro that started in business before 1816. In 19th-century China, he wrote, there were two carding mills on the West Branch of the Sheepscot River, in Branch Mills, one north of Main Street and one south.

From the 1700s well into the 1800s, cattle, horses, mules, pigs, sheep, geese and other animals often shared common grazing land, instead of being fenced on their owner’s land. Animals that wandered off the common land could and often did damage gardens and crops.

At many early town meetings voters discussed the town pound, a feature of New England town life brought from the Old World. The pound was an area enclosed by walls of fieldstone, granite or wood, with a wooden gate, where stray animals were corralled until their owners reclaimed them.

Each town was legally required to have a pound and to appoint a pound-keeper to round up and restrain loose livestock. To reclaim a strayed animal, the owner was usually required to pay a small fee to the pound-keeper and to recompense any neighbors whose property the animal had damaged.

The first town meeting in Vassalboro, held May 2, 1771, elected 22 town officials, including four hogviewers, but there is no record of a pound or pound-keeper. Historian Robbins quoted another vote from the record: “Swine shall run at large without ringing, with a yoke on their necks according to the law.”

The warrant for the Sept. 9, 1771, Vassalboro meeting asked voters to decide “what the Town will do about Pounds.” What the town did was vote to build two pounds before June 5 [1772], on two specified lots, and to have town residents build them on the first Monday in December 1771, with absentees to be fined “two shillings and eight pence Lawful money.”

Kingsbury adds that the dilapidated remains of a 19th-century stone pound were still standing in Vassalboro when his history was finished in 1892.

Albion’s first town meeting, when the future town was still Freetown Plantation, was held Oct. 30, 1802, Wiggin wrote. Apparently it was not until the fifth meeting, on April 16, 1804, that voters in what was by then the Town of Fairfax elected a pound-keeper (unnamed). Wiggin recorded that the April 1804 meeting also banned horses from the common and prohibited swine running at large.

A March 1805 Fairfax meeting approved a town pound. A month later voters reconsidered and reapproved the question and, Wiggin related, provided detailed specifications.

The pound was to be 32-feet-square. Walls more than four-feet-tall were to be supported by eight-inch cedar posts and made of five-by-four-inch ash or pine rails. The gate was to be hung on iron hinges, with a lock and key.

The pound was to be by Abraham Copeland’s house, and he was chosen pound-keeper. The bid to build it was awarded to Thomas J. Fowler, low bidder at $37. Presumably he met the voters’ June 20 deadline.

At the same meeting voters decided that neither hogs nor sheep could run loose, except that “Phineas Farnham’s sheep shall have the privilege of the road the width of his lot.”

(When William Chalmers was chosen tax collector at the Oct. 30, 1802, meeting, Abraham Copeland and Phineas Farnham were his bondsmen, financially responsible for making sure he performed his duty. Their appointment suggests they were respected men of property.)

The 1805 wooden-walled pound lasted until 1822, when a March town meeting approved Joel Wellington’s offer to build a new one for $20. It was to be near Edward Taylor’s house, and Taylor was chosen pound-keeper.

Kingsbury wrote that in 1803 voters in Harlem, now China, banned geese from the common. They must have approved building a pound around the same time, because Kingsbury said that in 1805 Ephraim Clark (one of the brothers of Edmund Clark, whose homestead was a topic in the March 18 The Town Line history article) was chosen pound-keeper, and reportedly held the job until he died in 1829.

In a meeting sometime between 1801 and the end of 1804 in Great Pond Plantation (later Palermo), voters decreed that hogs running at large had to be both yoked and ringed. Those who were not were impounded by the hogreeves. Voters chose as many as 14 hogreeves some years, Milton E. Dowe wrote in his 1954 Palermo history.

Fairfield, by contrast, at its first town meeting on Aug. 19, 1788, elected a single “Hog Ref,” one Thomas Blackwell.

At Palermo’s first town meeting, held Jan. 9, 1805, Millard Howard found that voters elected Daniel Clay as pound-keeper, assisted by an unreported number of “field drivers, who were to control domestic animals running at large with the exception of hogs which were controlled by hog reeves.”

The compilers of the Fairfield Historical Society’s history located a pound in Larone, the settlement on Martin Stream in the northern end of town, close to Norridgewock. Citing an earlier history of Larone and giving no dates, they wrote that the pound was 40-feet square and six-and-a-half-feet high. Town records credit 17 men who each gave a day’s work to build the pound.

For some farmers, by the middle of the 19th century, livestock had moved from an essential part of life and livelihood to a source of prestige. Local histories include accounts of breeders who made Maine nationally famous with their prize-winning cattle and especially their speedy trotting horses.

One of the latter, described by E. P. Mayo in his chapter on agriculture in the Waterville centennial history, was Nelson, born in 1882 and described on-line as “the only Maine bred trotting horse to be elected as an immortal in the Harness Racing Hall of Fame.

Thomas Stackpole Lang, of Vassalboro, brought Nelson’s maternal ancestor to Maine around 1860, and C. H. Nelson, of Waterville’s Sunnyside Farm, brought his sire from Massachusetts. C. H. Nelson was the horse’s breeder, owner, trainer and driver.

Nelson won his first Maine State Fair races as a two-year-old and a year later as a three-year-old. As a five-year-old he won a New England race. In 1890 and 1891 he set records in Indiana and Michigan and was much admired throughout the mid-west, and afterward continued to race in New England and New Brunswick.

Currier & Ives made six prints of Nelson. Other Maine trotting horses who were subjects of Currier & Ives prints include Lady Maud and Camors, two of many horses sired by Lang’s General Knox.

Mayo described a famous race between General Knox and Hiram Drew, bred by J. L. Seavey, of Waterville. Held Oct. 22, 1863, in Waterville, it drew a large and excited crowd from all over Maine. General Knox won.

Cattle breeders Mayo mentioned include Col. Reuben H. Green, of Winslow, one of the people who first brought Durhams to the area; Joseph Percival (Devons); Dr. N. R. Boutelle, owner of the Millbrook Herd, and others, including William Addison Pitt Dillingham (profiled in the March 18 The Town Line), who introduced Jerseys; and Hon. Timothy Boutelle, of Waterville, and John Damon Lang, of Vassalboro, (Ayrshires).

Mayo credits Green with the introduction of Bakewell sheep (better known as Leicesters; Robert Bakewell [1725-1795] was a British farmer famous for introducing selective breeding techniques to produce improved cattle, horses and sheep). Dr. Boutelle was one of the first to breed Merinos, and Joseph Percival, of Waterville, and Warren Percival, of Vassalboro, were Cotswold breeders.

John Damon Lang (1799-1879) was the first owner of the large farm on Dunham Road, the section of Old Route 201 south of Getchell’s Corner, that was later Hall Burleigh’s. He was also instrumental in developing the woolen mill that became the economic heart of North Vassalboro; his son, Thomas Stackpole Lang, was mill agent in the mid-19th century.

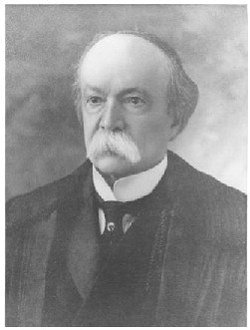

Hall C. Burleigh, born in 1826, grew up on a farm in Fairfield and in 18881 moved to the former Lang farm, in Vassalboro, with his wife, Clarissa K. (Garland) Burleigh and their 11 children. Well before then he had been breeding cattle, specializing in Herefords; by 1860 he was exhibiting in Maine and by the 1870s was recognized throughout New England and beyond.

A Henrietta, Texas, cattleman, Captain W. S. Ikard, reported attending the September 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where he saw Burleigh’s Herefords, including a bull named Compton Lad. Burleigh’s and other Herefords so impressed him that he is credited with importing the first Herefords into Texas.

In 1879 Burleigh went into partnership with former Maine Governor Joseph R. Bodwell. The two imported close to a thousand head of cattle that Burleigh chose from all over Britain. An 1893 on-line biography says by 1893, Burleigh’s cattle had won “more prizes in the show rings of the United States than those of any other individual in America.”

Next: agricultural organizations

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 (1954).

Dowe, Milton E., Palermo, Maine Things That I Remember in 1996. (1997)

Fairfield Historical Society, Fairfield, Maine 1788-1988 (1988).

Howard, Millard, An Introduction to the Early History of Palermo, Maine (second edition, December 2015).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902)

Wiggin, Ruby Crosby, Albion on the Narrow Gauge (1964).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!