Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Natural resources – Part 2

by Mary Grow

Rocks & clay

Last week’s article talked about some of the towns in which European settlers found naturally-occurring resources, like stones and clay. Stones were described as useful for foundations, wells and similar purposes on land; another use was for the dams that have been mentioned repeatedly.

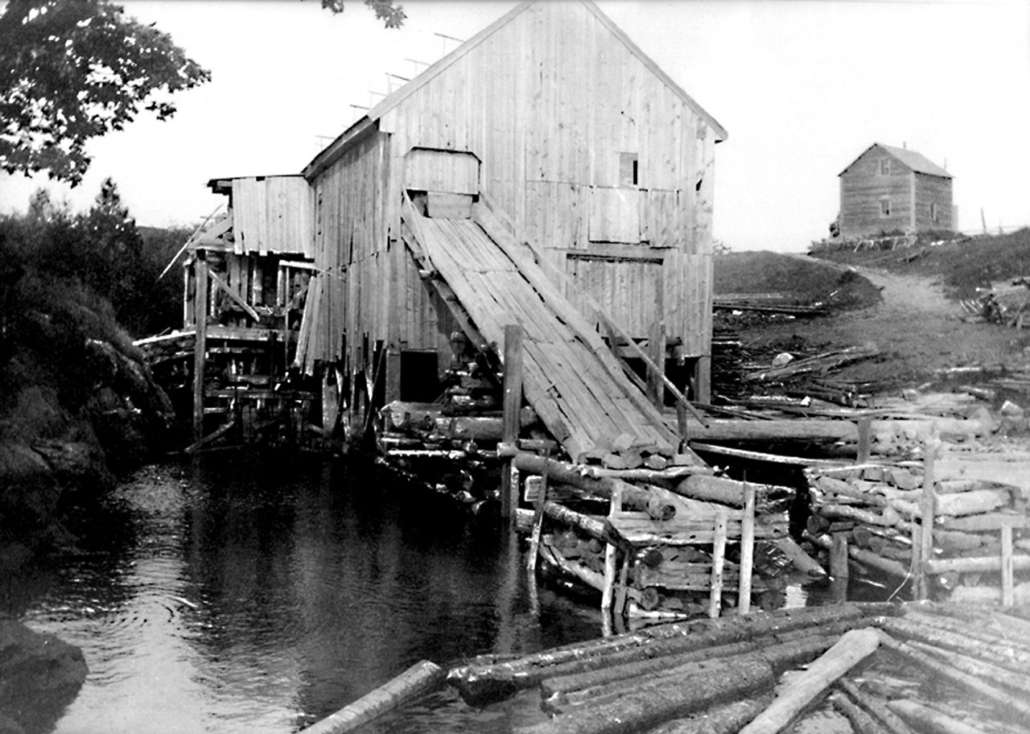

Palermo historian Milton Dowe, in his 1954 town history, said settlers coming to the area then called Great Pond Settlement (because it was near the head of Sheepscot Great Pond) in the late1770s lived in log houses until entrepreneurs built sawmills to make boards. The prerequisite for a sawmill, he wrote, was “a dam of rock and dirt on a brook of almost any size.”

The majority of local histories describe early water-powered mills in Kennebec Valley towns, most built on streams (many of them tributaries to the Kennebec) before men had the courage to try to dam the larger river. Assuming a dam for each mill or cluster of mills, thousands of stones must have been moved.

In Vassalboro in the 1820s, according to an unnamed source quoted in Alma Pierce Robbins’ town history, there were “19 water powers,” presumably dams and presumably at least partly made of stone. Thirteen were on Outlet Stream, which flows north from China Lake through East and North Vassalboro to the Sebasticook; the other six were on Seven Mile Stream, Webber Pond’s outlet into the Kennebec.

Windsor historian Linwood Lowden described the agreement that allowed the building of an 1809 dam across the West Branch of the Sheepscot River, at Maxcy’s Mills, in Windsor. Cornelius Maguire and Joseph Linscott signed a 15-year lease allowing Joseph Bowman, from Gardiner, to dam the river and build a sawmill.

Bowman’s lease included land on each bank to anchor the dam, and “the right to as much gravel, dirt, timber or stones” as he needed, except he could not cut pine or oak. Other Windsor streams also had mills; the remains of some of the mill dams were visible in 1993, Lowden wrote.

Robbins and Dowe mentioned another use for stone: building bridges. Robbins found that an 1831 town meeting voted to build a stone bridge “near Jacob Southwick’s plaster mill.” In 1841, Dowe wrote, Palermo town meeting voters appointed a three-man committee to oversee construction of a 640-foot-long bridge “of stone covered with earth,” a four-year project.

Stone has multiple meanings, and historians seldom specify what size, shape or material they’re talking about. Stones interrupting plowing are not the same as the stone in Thomas Saban’s Palermo quarry “near the head of Sheepscot Lake” that Dowe described.

Dowe wrote: “Here the stone was found in layers of various thicknesses all standing on edge from the upheaval of the earth centuries ago. To obtain any size wanted the stone was drilled and wedged.” The two specific uses he cited were steps and well covers.

(Wikipedia provides engineering information on wedging. The process could work several ways. If the stone had natural cracks, steel wedges were hammered into the cracks to split the stone into desired sizes. If there were no cracks, the quarryman made some. He drilled a row of holes, into which he inserted conical wedges called plugs and flat wedges called feathers and hammered them; or, one source says, he put wooden plugs with the feathers and wetted the plugs so that they expanded and broke the stone.)

* * * * * *

Bricks, their production and uses, were the focus of last week’s article, and, as usual, your writer found more than a page’s worth of information, so this week’s installment will continue the topic.

Robbins tossed off a comment in her Vassalboro history, in a section on early settlers: “Bricks were a great business, developed almost as soon as the sawmills according to most histories of Maine. (The town records confirm this statement.)”

There were several brickyards in Palermo, Dowe said. One, not long after 1800, was on the Marden brothers’ property (presumably in the Marden Hill area, east of Branch Pond); they sold their bricks to neighbors for “chimneys; fireplaces and brick ovens.” A mixture of ashes and clay made mortar, Dowe added.

Another 19th-century brickyard was “in the meadow… where clay was very plentiful” on the Sumner Leeman farm near Greeley Corner, the intersection of what is now Route 3 with Turner Ridge Road, east of the head of Sheepscot Lake.

Sidney had at least one brickyard in 1780. The quotation from Robbins’ Vassalboro history about the importance of brickmaking was in reference to a proposed road on the west side of the Kennebec River (in what became the separate town of Sidney in 1792) that was to follow a way already in use “on the east side of the Brick Kiln at Dudley Does.”

Kingsbury in his Kennebec County history and Alice Hammond in her Sidney history agreed Sidney had many clay deposits. As Kingsbury put it, “wherever bricks were wanted for one or more buildings in times past, when wood for burning them was always at hand, they were made in that locality.” Kingsbury said one yard (perhaps Doe’s) was producing “excellent brick” before 1800.

Hammond mentioned two houses on Middle Road made of brick, reportedly from a nearby brickyard by a brook, and three early River Road farms with brickyards. Perhaps citing Kingsbury, she wrote that in 1860 Nathaniel Chase’s bricks from the Bailey farm (one early Bailey farm was Paul and Betsy’s, on River Road across the Kennebec from Riverside in Vassalboro) “were transported by flat boat to the Augusta market.”

In Vassalboro, Robbins wrote that the Farwell family, Isaac (1704 – 1795) and his son Ebenezer, acquired large tracts in the southern part of town in the 1760s. Their holdings included land around Seven Mile Stream, where they built early mills, and extended south; Isaac built for Ebenezer the large house with white columns called Seven Oaks, still standing on the east (river) side of Riverside Drive (Route 201) near the Augusta line.

Robbins wrote that Isaac’s first house was near a brook – probably Seven Mile Stream – on which he built “a grist mill, saw mill and brick kilns.”

(Another prominent family in southeastern Vassalboro were the Browns, Benjamin and his son Benjamin, Jr. Robbins did considerable research to record their contributions to the town and the area. Riverview, their 1796 one-and-a-half-story Cape house on Riverside Drive, has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 2001.

(Robbins wrote that when Benjamin Brown needed bricks for fireplaces in his “large and quite handsome tavern” that he built sometime before he became postmaster in 1817, he imported them from England. Were the Farwell kilns closed by then? Quite likely; or perhaps the Farwell bricks were not to Brown’s taste.)

And here is another question Robbins raised: did “John DeGrucia, brickmaker,” make bricks in Vassalboro in the 1770s? She wrote that in 1769, DeGrucia “gave bond for forty pounds to Samuel Howard, mariner, for land on the east side of the river on Lot No. 80”; she didn’t mention him again. (Lot 80 is one tier inland from the Kennebec River and about half-way toward Vassalboro’s north boundary.)

In 1806, Robbins found, town meeting voters elected a “Surveyor of Bricks,” apparently for the first time.

When John D. Lang started his first woolen mill, in North Vassalboro, in 1850, Kingsbury wrote that he bought and moved a tannery building. Then he had a brick kiln built on the site, “and after the brick were burned the walls of the mill were built around it.” The mill was added to the National Register of Historic Places on Oct. 5, 2020.

Your writer was unable to find information about Windsor brick production in available sources. Kingsbury made one reference: Thomas Le Ballister, from Bristol, acquired 300 acres in southeastern Windsor and built a log cabin around 1793. When he upgraded to a frame house about 1803, “The chimney was laid with the first bricks manufactured in Windsor.”

In Winslow, Kingsbury listed eight or nine places with “good clay for making brick,” identifying their locations by their pre-1892 owners. A major operation started in 1873 was by 1892 Horace Purinton & Co., with a workforce of 15 and an annual production of 1.5 million bricks.

Kingsbury also described a series of mills built by men named Runnals, Norcross and Hayden on a stream he did not name (identifying it by the mills still operating in 1892). Other sources’ information on the family names suggest it might be Chaffee Brook, which runs into the Kennebec in southern Winslow.

Hayden’s mill dam backed up the stream to make Hayden Mill Pond, and Kingsbury wrote that on one side of the pond was a bed of clay good enough to make pottery. William Hussey, a skilled potter, and Ambrose Bruce started a pottery factory in the late 1820s.

Kingsbury wrote that Hussey’s earthenware was popular – “Most of the milk pans then in use by the housewives in this section were his handiwork.” Unfortunately, according to Kingsbury, Hussey was “[t]oo fond of convivial enjoyments” and drank up so much of the proceeds that the pottery went out of business.

William Hussey is listed in Lura Woodside Watkins’ Early New England Potters and Their Wares, originally published in 1950.

Winslow buildings using brick that Kingsbury mentioned included a century-old house standing in 1892, made of brick from an adjacent yard “near the river two miles above Ticonic falls”; and an early tavern “in a house with a brick front” south of the junction of the Sebasticook River. The Hollingsworth and Whitney mill building, under construction as Kingsbury finished his history, required 2,500,000 bricks, he said.

Winslow’s brick schoolhouse on Cushman Road, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, was described in the Jan. 28, 2021, issue of The Town Line. Two other brick school buildings in Winslow were mentioned in the Oct. 28, 2021 issue.

Update on Fairfield Center’s Victor Grange

Members of Victor Grange #49, in Fairfield Center, organized Oct. 29, 1874, continue to make progress on rehabbing their Grange Hall, which dates from 1903 (see the May 13, 2021, issue of The Town Line). The Grange’s July newsletter reports the building is insulated and as of mid-June has a ventilation system.

The next ambitious project is to have the ground-level hardwood floors professionally refinished, Grange Lecturer Barbara Bailey believes for the first time ever. Grange members need volunteers to help move the furniture from the building to a storage trailer on July 24, beginning about 11 a.m., and will need them again to move everything back about two weeks later. They offer hot dogs and hamburgers to the July 24 crew.

Funds have been donated; Timmy’s Trailers, aka C and J Trailer Repair and Towing, of Fairfield, has loaned the trailer; and Pro Movers, of Waterville, will move out, store and return two pianos.

As a fundraising effort, Grangers are selling more than six dozen 1880s chairs from the organization’s early days, at $10 apiece.

The newsletter writers expressed their appreciation to community members who support the Grange and included the weekly and monthly schedule of ongoing public events. People listed as sources of information about Grange activities are Rita, 453-2945; Roger or Wanda, 453-7193; Marilyn, 453-6937; Deb, 453-4844; Barb, 453-9476; Rick or Lurline, 453-2082; Janice, 453-2266; Steve, 347-254-8556; Anastasia, 835-1930; Tina, 649-5396; and Sherry, 238-0334. The email address is Victorgrange49@gmail.com

Main sources

Dowe, Milton E., History Town of Palermo Incorporated 1884 (1954).

Hammond, Alice, History of Sidney Maine 1792-1992 (1992).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892),

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!