Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Rufus Matthew Jones, of China

by Mary Grow

China native Rufus Matthew Jones was another writer with a religious background, like Sylvester Judd, though both his religion and his writing style were quite different. Various sources describe him as a philosopher, religious leader, theologian and mystic; he was also a writer, magazine editor, historian and educator.

Jones was born Jan. 25 (or, in Quaker terms, first month, 25th day), 1863, son of Edwin Jones (April 6, 1828 – July 23, 1904) and Mary Gifford (Hoxie) Jones (Sept. 26, 1833 – March 7, 1880).

Several of his more than three dozen published books are about his family and his own life. The first, in the spring of 1889, was his biography of aunt and uncle, Eli and Sibyl Jones.

His own life story Jones wrote partly in reverse order. A Small-Town Boy, detailing his early life in China, came out in 1941. It was preceded by Finding the Trail of Life (1926); The Trail of Life in College (1929, including in the introduction the possibility that after 40 years his memory might be fallible); and The Trail of Life in the Middle Years (1934).

Despite his many writings on Quakers and their beliefs, Jones wrote in his chapter on the Society of Friends in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history:

The history of the Friends in this county can never be adequately written, since from their first appearance until the present time they have done their work in a quiet, unobtrusive way, leaving behind them little more record of their trials and triumphs than nature does of her unobserved workings in the forests; but this fact does not make their existence here unimportant, and no careful observer will consider it to have been so.

Jones wrote in A Small-Town Boy of growing up in a three-generation household, the third of four children. Brother Walter Edwin (1853-1895), 10 years older, left home while Jones was young, leaving the youngster feeling as though “the bottom had dropped out.”

Sister Alice (1859-1909), four years older, was Jones’ “second mother” and “happy playmate” until he “broke away and formed my indispensable group of boys.” Brother Herbert Watson (1867-1918) was “a perfect dear,” but too much younger to share many of Jones’ activities.

The first chapter of A Small-Town Boy is a summary history of China, the town Jones always loved. The second chapter is about his family, and the third about Friends’ meeting. After that come chapters on other influences: “the old-time grocery store,” school, play, important townspeople and town meeting.

Parents and children lived with Jones’ grandmother, Abel Jones’ widow Susannah, until she died in 1877, and her younger daughter, Peace (1815-1907). It was his grandmother, Jones wrote, who started him reading the Bible during a year-long illness when he was 10.

Aunt Peace he called a remarkable woman, unschooled but cultured, wise, well-informed, insightful, one of the rare people in whose ear God whispered, a mystic without knowing it. After she explained a moral issue, “there was only one right course open,” whether her nephew liked it or not.

Jones described the three adult women in the household as loving and supportive of each other and the rest of the family. The death of his mother when he was 17 was a deep grief.

His father, Edwin, was physically strong and a skilled workman, though not intellectual. Neither parent disciplined the children; a word or look of reproach was sufficient.

The parental attitudes, the Bible-reading, the silent morning devotions, created a nurturing home that was profoundly religious in the Quaker fashion. Jones wrote, “The life in our home was saturated with the reality and the practice of love.”

Abel Jones built the family house in 1815 on what is now Jones Road, in South China, running northeast from the four corners that used to be the village’s commercial center. The Federal-style house has been on the National Register of Historic Places since 1983.

The meeting house the Jones family attended on Thursdays and Sundays was three miles away, Jones wrote – the 1807 Pond Meeting House (also on the National Register of Historic Places since 1983). It stands on the east side of what is now Route 202; Jones described the trip as “a drive in wagon or sleigh through the ‘dangerous’ woods,” full of wild animals.

Meetings consisted of long periods of silence, which Jones said were filled with “a sense of divine presence which even a boy could feel.” Occasionally someone would be moved to offer a prayer or a reflection.

The talk might be an inspiring message from a genuine leader, local or visiting. Or someone recognized as among the “one-talent exhorters, or peradventure quarter talent speakers” might deliver a repetitive and unimportant message, loudly and with wild gestures.

Once a month the Friends’ worship meeting was followed by a business meeting. Jones described how, after an older man announced the transition, wooden shutters dropped down with “a strange creaking” to divide the room and let men and women meet separately.

Men’s business Jones summarized as “a searching inquiry into the state and condition, the moral and spiritual progress or decline, of the membership.” There might be specific requests as well: to accept a new member, release a member whose beliefs or behavior were no longer appropriate, investigate the “clearness from other engagements” of a couple wishing to marry or permit a member to undertake a missionary journey.

(In the section on Quakers in her history of Sidney, Alice Hammond wrote that the men’s meeting decided issues of “civics, education, finances, etc.” The women’s “ascertained the correct social form” of the members. She quoted from reports of early 19th-century women’s meetings investigations of proposed marriages, criticism of a woman “addicted to the custom of too freely partaking of spirituous liquors” and a request to accept a new member moving to Sidney from New Hampshire.)

As Jones was growing up in South China in the 1860s and 1870s, the local grocery store was “the center of village culture,” he wrote. From his description, the store in question was almost certainly the one at the four corners described in the China bicentennial history as dating from the 1830s.

The history says Samuel Stuart owned the store when a fire in 1872 destroyed most of the village’s central commercial area. Stuart rebuilt the store and ran it until about 1879, when his son Charles Stuart took over until September 1888.

Jones said the store had a wooden front platform, with cracks through which a boy could accidentally lose his pennies; shelves and a counter; a barrel stove surrounded by chairs; and a “box of saw-dust for the tobacco chewers, who in the good old times could infallibly ‘hit it’ from any location.”

About 15 local men generally hung out at the store, more “at mail-time in the evening” – the store was also the post office, one reason, Jones said, that he was allowed to go there so often – and on rainy days. The storekeeper joined their discussions; and, Jones wrote, “his son and successor” was an even more important participant.

This man, according to Jones, “had served in the Civil War, had lived in Boston, had had a term in jail! He knew the world from inside out and had tales to tell about the ways of the world.”

This man (Jones never did name him in A Small-Town Boy) became Jones’ good friend, taught him to sail on China Lake and let him help in the store. Jones wrote that his upbringing enabled him to hear cursing and vulgarity without joining in, and that mixing with this group taught him to get along with different kinds of people.

Store conversations varied from anecdotes and wisecracks to local, state and national politics. James G. Blaine, of Augusta, was the store-sitters’ hero and perennial presidential nominee, though the majority of the country never agreed to elect him.

One day, Jones wrote, Blaine himself stopped his “span of well-groomed horses” at the South China store. Jones was in the forefront of the admiring crowd, and Blaine asked him to water the horses.

“As a Quaker, I had never yet said ‘Sir’ to any body,” Jones wrote, and he still couldn’t, even to his “greatest living hero.” He replied, “It will give me great pleasure to bring water for thy horses, James G. Blaine.”

Jones watered the horses. Blaine, knowing a tip would be “an impossible breach of good manners,” exchanged a few sentences with the boy and drove off. Jones was a local “near-hero” for days thereafter.

To be continued

The history of the Quakers

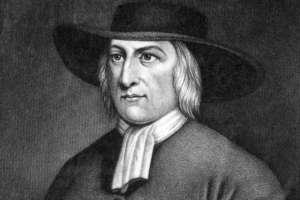

The history of the Quakers, properly known as the Society of Friends, begins in England in the 1650s, with a man named George Fox (1624-1691).

Fox and his followers rejected the dominant Church of England. They believed in a direct relationship between God and the individual, not mediated by a religious hierarchy. A history on a Vassalboro Friends Meeting website says, “Quakers rejected outward sacraments and priestly orders, depending instead on the inward power of Christ’s example for guidance.”

Early Quakers gave women a more important role than elsewhere in society, emphasizing the role of mothers in raising children in faith, piety and love. Quakers were from the beginning anti-slavery and anti-war, often putting them at odds with the dominant society.

Despite persecution in the 1660s, Quakerism spread in England and Wales and was soon imported to the colonies in North America. Massachusetts Puritans initially opposed the doctrine, imprisoning and executing practicing Quakers. Other colonies were more tolerant.

Like other religions, the Society of Friends had its divisions that created schisms and subgroups in the 18th and 19th centuries. And like other religions, British and American Quakers sent missions to other parts of the world.

In 1775, Rufus M. Jones wrote in his history of the Society of Friends in Henry Kingsbury’s Kennebec County history, a New York Quaker named David Sands made the first of his four trips to the Kennebec Valley. He and his companions stopped at the home of Remington Hobbie, an early settler in Vassalboro, whom Sands converted to Quakerism.

In addition to Sands’ influence, the Vassalboro Friends website says that during the American Revolution, their pacifism made Massachusetts Quakers unpopular. Many moved to Vassalboro, China, Sidney and Fairfield in the 1780s and 1790s.

Jones said the first meeting in Vassalboro was organized in 1780, and the first meeting house was built, in two sections, in 1785 and 1786.

Vassalboro’s meeting included members from China, Sidney and Fairfield before those towns had their own meetings and meeting houses. In China, Jones said, half the Clark family (the mother and two of four sons), who were the first settlers around China Lake in 1774, were Friends.

Jones wrote that the first meeting in Sidney was in 1795. Fairfield Quakers also attended; meetings still alternated between the two towns in 1892, he said.

Alice Hammond, in her 1992 history of Sidney, said in 1806 Sidney Friends bought an acre on Quaker Hill Road “where a church had already been built,” plus a half-acre nearby for a cemetery.

The 1988 Fairfield bicentennial history has contradictory information. It says Quaker Elihu Bowerman and his brothers settled in North Fairfield in 1782 and attended the Vassalboro meeting for about 10 years, until they began meeting in one of the Bowerman brothers’ log cabins; it also says Fairfield’s first Friends meeting house was built in 1784.

Main sources

Jones, Rufus Matthew, A Small-Town Boy (1941).

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Correction to Meeting House location

Your writer was probably in error when, in the April 25 article on Rufus Jones, she cited the source that said the family drove from South China north (on what is now Route 202) to the Pond Meeting House twice weekly, while he was a child in the 1860s and 1870s. Elizabeth Gray Vining, in Friend of Life: The Biography of Rufus M. Jones, wrote that his family worshipped at the Friends meeting house at Dirigo.

A reference in Jones’ Finding the Trail of Life to the road through the woods to meeting as “hilly” supports Vining: current Route 3 east to Dirigo is hillier than Route 32 north to Pond Meeting House.

The Dirigo meeting house was abandoned in 1884, when Friends meeting moved to South China Village. Your writer found no information on how long it had been used.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!