Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Wars – Part 2

by Mary Grow

by Mary Grow

As readers know, major wars have major effects, beginning before the battles, continuing for the duration and lasting years afterwards. Early historians tended to focus on economics and politics: whether development was slowed or speeded or both, who replaced whom in leadership. Later came interest in social effects, especially significant in the aftermath of the Civil War.

Individual psychological effects of war, now commonly labeled PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder), have been recognized for centuries, but did not receive a lot of attention until the present century. A 2017 Smithsonian magazine article found on line discusses psychological effects suffered by Civil War soldiers, though not under the modern name.

Some of these young men, far from home and family and witnessing the horrors of face-to-face war, developed “what Civil War doctors called ‘nostalgia,’ a centuries-old term for despair and homesickness so severe that soldiers became listless and emaciated and sometimes died,” according to the article. Others had physical symptoms, like “soldier’s heart” (chest pain, difficult breathing, palpitations), or mental breakdowns.

After World War I, PTSD was called “shell shock.” “Combat fatigue” was the best-known of several terms used after World War II.

It is unlikely that 18th and 19th century soldiers from the Kennebec Valley avoided psychological stress, but finding records demonstrating the condition would be even more unlikely. There are, however, numerous reports on and analyses of economic consequences, and social and political consequences are sometimes obvious.

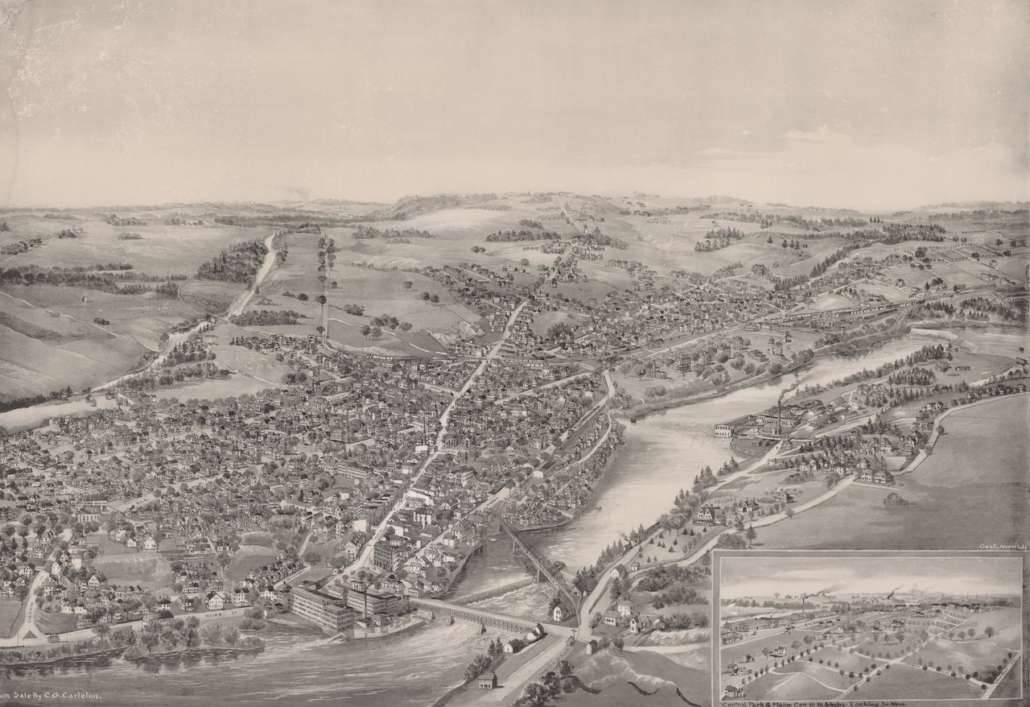

Many of the central Kennebec Valley towns, especially the larger ones, suffered economic distress during the Revolution. The level of distress in Augusta (then Hallowell) is recorded by historians Henry Kingsbury and Charles Nash.

Kingsbury summarized: “A town of so few inhabitants, however willing, could not give much aid to the continental cause, and its part in the war was necessarily small and inconspicuous. It suffered much during the period of the revolution – its growth was retarded and well-nigh suspended….So great was the depression that even the Fourth of July Declaration [of Independence] was not publicly read to the people.”

Nash wrote that by 1777, British warships so “infested” the Maine coast as to practically stop overseas trade, a blow to the shipbuilders and shipmasters of Hallowell (and downriver towns). A year later, though, he wrote that a Hallowell shipbuilder sold the government hundreds of pounds worth of ships’ masts, spars and bowsprits for the budding Continental navy.

According to Kingsbury, only about 100 heads of families lived in Hallowell in 1779, presumably after many Tories had left. When the new national government started assessing towns individually for soldiers and supplies, townspeople could not easily meet the demands.

By the 1780s, according to information Nash compiled from town meeting records, Hallowell voters were raising money to pay soldiers. In October, for example, they raised 12,000 pounds to pay $500 each to soldiers who served eight months in Camden. Many were paid in lumber or shingles instead of money.

Another series of votes in January 1781 raised 90 guineas (Wikipedia says a guinea was about the same value as a pound) for six men to “go into the service of Massachusetts” (Kingsbury added that they were required to enlist for three years); directed that “the selectmen and commissioned officers shall do their endeavors to procure said men”; and for that purpose directed them to “hire money upon the town’s credit.”

That the effort was not fully successful can be inferred from the February vote to “petition the General Court [of Massachusetts] for relief of the beef tax, and our quota of soldiers sent for from this town.”

In March, annual meeting voters gave town leaders “discretionary power to get the continental men in the best way and manner they can be procured.”

Nash found a September 6, 1781, vote (three weeks before Cornwallis’ surrender at Yorktown) that sounded even more desperate. Voters directed selectmen to “endeavor to procure this town’s quota of shirts, stockings and shoes and blankets required of this town, upon the town’s credit if they can be procured.” Kingsbury detailed the requisition: “2,580 pounds of beef, 11 shirts, 11 pairs of shoes and stockings, and 5 blankets,” and said the Massachusetts legislature threatened to fine the town if it did not produce.

From what little Whittemore wrote in his history of Waterville, the townspeople in what was until 1802 Winslow on both sides of the Kennebec also had trouble meeting quotas. Town officials had neither money for supplies nor willing volunteers for soldiers. The price of beef rose to five dollars a pound, indicating, Whittemore said wryly, “either a depreciated currency or that some primordial beef trust already had taken possession of the country.”

He was serious about the depreciated currency. Nash gave examples through the 1770s of a steady decline in the value of the paper money issued by the new government.

By 1781, he wrote, currency was worth so little that the government made a “new emission.” Defined as legal tender and valid for paying taxes, Nash wrote that it held its value briefly, but within a few months it lost almost half its value, a dollar becoming the equivalent of a half-dollar in silver.

Ernest Marriner picked up the theme in his Kennebec Yesterdays. Money, either paper currency or coins, was scarce in the valley anyway, he wrote; people often paid for things they could not make at home with things they could, especially crops, like wheat, corn, peas, potatoes and apples, and also butter, cheese, wool, flax and similar products.

The naval supplies Nash described were paid for partly in dollars (presumably Continental paper currency), with 100 dollars equal to 30 pounds, but also in corn, “New England rum,” sugar and glass.

Marriner found that by 1789, a Continental paper dollar was worth one-fortieth of a silver coin. By then, he wrote, hay, previously costing a maximum of $10 a ton, was $200 a ton. Butter cost $1.50 a pound; by 1802, it was down to 15 cents a pound.

Many Kennebec Valley families were left in precarious circumstances by the combination of limited access to outside supplies; heavy taxes to support local, Massachusetts and federal military and civilian needs; depreciated currency; and breadwinners off fighting, home recovering, in a British military prison or dead.

Nash quoted from the journals and letters of Rev. Jacob Bailey, a Tory who lived in Pownalborough (now Dresden) for most of the war years. Bailey referred to “nakedness and famine” among his neighbors.

Some had no bread for months, he wrote. It was impossible to find grain, potatoes or other vegetables; meat, butter or milk; tea, sugar or molasses. People lived on “a little coffee, with boiled alewives or a repast of clams,” and not enough of that diet to forestall hunger, Bailey wrote.

* * * * * *

Tories, especially outspoken ones like Bailey, were a minority in the Kennebec Valley, and became a smaller minority as the war went on. When it became clear that the rebellion was succeeding, fence-sitters joined the winning side; opponents of independence went away, usually to eastern Canada.

In the Hallowell area, many of the big landowners, like the Gardiner, Hallowell and Vassall families for whom towns were named, were British sympathizers. During or after the war, they emigrated to Canada or Britain; post-war local governments confiscated their lands.

A notorious Tory in the Augusta area was John “Black” Jones (c. 1743 – Aug. 18, 1823).

Nash wrote a great deal about “Black” Jones in his Augusta history, distinguishing him from three other men named John Jones who were in the area earlier or simultaneously. The Tory Jones’ primary work was surveying for the Plymouth Proprietors, laying out lots on both sides of the Kennebec River, including the future towns of Hallowell/Augusta, Vassalboro, China, Unity and Skowhegan. Kingsbury added that he built the first mill on the west side of the Kennebec at Hallowell.

“Black” is said to have referred to his dark complexion, not his character. Indeed, Nash wrote that he was “a skillful surveyor and a man of good character,” who was repeatedly elected to local office in 1773 and 1775, despite being stubbornly pro-British in a divided community.

In April 1777, Nash found, town meeting voters chose Lieutenant John Shaw “the man to inspect the tories, and make information thereof.” At another meeting in July, they implemented a Massachusetts law intended to protect the country from “internal enemies” by instructing Shaw to collect evidence against Jones, “who they suppose to be of a disposition inimical to the liberties and privileges of the said States.” In Oct. 1777 they again voted Jones “inimical to the liberties and privileges of the United States.”

After a brief imprisonment in Boston, Jones escaped and went to Canada, where he enlisted on the British side. Assigned to Fort George, in Castine, he led a band of soldiers who raided local rebel towns. An on-line Canadian biography says he worked as a surveyor in New Brunswick, Canada, after the war.

Returning to Hallowell, according to Nash as early as November 1785, Jones was met by antagonists who escorted him out of town. He came back, and, Nash wrote, “by his many good qualities and an exemplary life he largely overcame, long before his death, the bitter prejudice which his attitude and acts during the revolution had aroused in his fellow-citizens.” Kingsbury wrote that in 1794 it was Jones who surveyed the division of Hallowell into three parishes.

Another mention of Tory sentiment is in Alma Pierce Robbins’ history of Vassalboro. She gave the Revolutionary War only a few sentences, mostly focused on Congress’s approval of aid and pensions to soldiers and their dependents.

Robbins said records indicated that Vassalboro residents were “somewhat lukewarm” patriots who “did their share in a dilatory manner.”

She added, however, that town officials fined “those who spoke too openly against the Revolution,” that the town’s beef quota was “finally” paid “under strong pressure” and that “many” did fight on the Revolutionary side.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Marriner, Ernest, Kennebec Yesterdays (1954).

Nash, Charles Elventon, The History of Augusta (1904).

North, James W., The History of Augusta (1870).

Robbins, Alma Pierce, History of Vassalborough Maine 1771 1971 n.d. (1971).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!