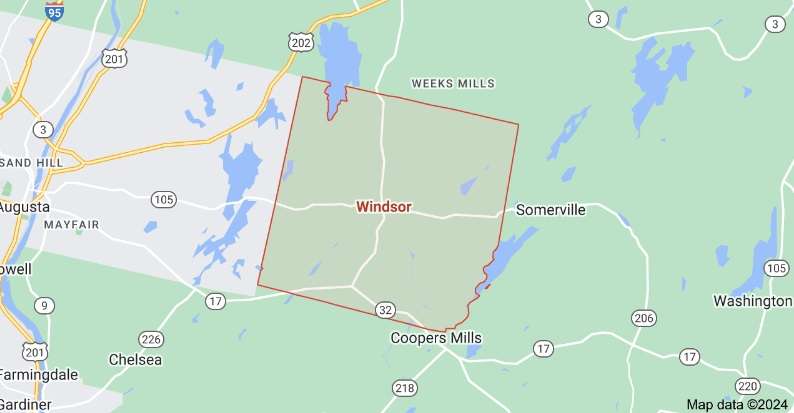

Up and down the Kennebec Valley: Windsor brooks named for early settlers

by Mary Grow

Last week’s article was about ponds in Windsor that were named after people who settled or lived near them. According to Henry Kingsbury’s 1892 Kennebec County history and Linwood Lowden’s 1993 Windsor history, several streams or brooks were also named in recognition of early residents.

Dearborn Brook is the newer name of what Lowden said was the Moody Pond outlet, called in an 1800 deed “Grover’s upper meadow brook on the east side of Oak Hill.”

Dearborn Brook has its origin in southwestern Windsor, near the Windsor-Whitefield town line. It wanders north and east most of the length of the town, with Moody Pond and two other widenings in southern Windsor.

The brook passes west of Windsor’s four corners (the intersection of north-south Route 32 and east-west Route 105); passes under Route 32; and joins the West Branch of the Sheepscot River in northern Windsor.

Besides Grover’s Brook, Lowden said this stream was also called Oak Hill Stream, Meadow Stream, Chases Brook and Colburn Stream or Colburn Brook.

Grover referred to Ebenezer Grover. Lowden identified him as the first man to settle in Windsor, choosing a piece of meadowland in the southeastern area called Pinhook (because of a U-shaped bend in the west branch of the Sheepscot).

Lowden found that Grover was born in York in 1724. He married Martha Grant of Berwick in August 1745; they lived in Georgetown and then in Whitefield on the way to what became Windsor.

Grover “laid claim to, and began to improve” the meadowland in 1781 (when he was 57, Lowden pointed out). He probably moved to Windsor permanently before 1786.

In 1797, Grover, his son Thomas, son-in-law Thomas Day and a neighbor named Abijah Grant had the area surveyed, trying to establish a claim that would compete with the British-based proprietors. Lowden devoted several pages of his history to accounts of Grover’s land dealings.

The historian wrote that Grover’s first home was evidently a house rather than a log cabin. He referenced a Sept. 2, 1797, plan by surveyor Josiah Jones showing “a small building with a glazed window.” It was on the west side of the Sheepscot and a little north of what is now Route 17, Lowden said.

The Grovers probably had three sons and four daughters. Lowden found evidence suggesting Martha Grover died before 1785, and Ebenezer lived with a son-in-law named Joseph Trask, Jr.

Lowden called Grover a man overlooked by historians, who should have credit for his role in Windsor’s early development. Specifically, he deserved recognition for the “first serious mapping” of the town, and for “his significant influence in attracting settlers to this area through his many land transactions.”

* * * * * *

Lowden’s lists of early Windsor settlers include no Dearborns, but the name appears in his history. Your writer has found no evidence explicitly linking the Dearborn family to Dearborn Brook, and no explanation for the stream’s name.

Henry Dearborn, of Pittston, bought half a grist mill at what became Maxcy’s Mills, southeast of the four corners, on May 6, 1823.

In or a bit before 1834, two Dearborns, Henry W. and Dudley T., were among Windsor residents signing a petition to the Maine legislature to dam the Kennebec River at Augusta.

In April 1847, after more than 30 years of declining to build a town house, Windsor voters decided they needed one. They appointed a three-man committee to draft plans and find a site, and on May 15, 1845, they bought William Haskell’s lot for $30.

The deed was signed July 10, 1845; and a second committee, consisting of Haskell, William Hilton and Henry Dearborn, was directed to hire a contractor, plan the building, oversee construction and “accept…the building on completion.”

The voters said work should be done by March 1, 1846, except the plastering – that deadline was June 1, 1846. The first town meeting in the new building started at 1 p.m. May 21, 1846, Lowden wrote.

Lowden quoted an additional provision that allowed “individuals” to add a second floor, providing they paid for it. Evidently they did, because he said this “upper story was used as a school” at first and later as a meeting room for town organizations.

In March 1921, Lowden said, voters decided to replace rather than try to repair the 1846 building.

The on-line site FamilySearch says Henry Wood Dearborn was born in Monmouth Aug. 2, 1798, older son of Dudley (1770-1848) and Keziah (Wood) (1765-1834) Dearborn. The younger son, Columbus, lived only from Sept. 13, 1802, to April 7, 1810. Two daughters lived to adulthood.

On Oct. 20, 1836, Henry married Judith Batchelder (1799-1888); they had “at least one son,” William H.

William H. Dearborn, according to FamilySearch, was born Oct. 13, 1840, in Windsor. In 1862, he enlisted for Civil War service, becoming a member of the 21st Maine Infantry regiment.

This regiment spent two months, from March 21 to May 21, 1863, encamped outside Baton Rouge, Louisiana. There must have been skirmishes with the Confederates, because on May 8, 1863, Lowden said, Dearborn was killed in action – one of at least five Windsor men from the regiment killed in that area that spring.

* * * * * *

Choate Brook was mentioned in the Feb. 15 article as the connection between Savade Pond, in northeastern Windsor, and the west branch of the Sheepscot River. This brook goes southwest under Greeley and Sampson roads and enters the Sheepscot a little west of Sampson Road and north of Route 105.

Lowden named two Choate brothers who were early settlers in Windsor Neck, the northeastern part of the town. They were Aaron Choate and Rufus Lathrop Choate, sons of Abraham Choate, Sr. (March 14 or 24, 1732-April 23, 1800), and his wife, Sarah (Potter) (died in 1811).

Abraham and Sarah were from Ipswich, Massachusetts. Lowden said Abraham came to Whitefield by way of Wiscasset, and owned an interest in a large sawmill at Kings Mills, on the Great Falls in the Sheepscot. An on-line history of Kings Mills says Choate acquired part of the mill and associated rights in 1779.

The genealogy lists Abraham and Sarah’s 14 children: Nehemiah (1757-1775, died on a privateer during the Revolution); Abraham, Jr. (1759-1837); Sally (1761-1837); John (1763-1800); Francis (1764-1799); Aaron (Feb. 7, 1766-March 18, 1853); Moses (1767-1851); the first Rufus Lathrop (1769-1769; lived for less than four months); the second Rufus Lathrop (1770-1771, lived about eight months); Rufus Lathrop (Feb. 28, 1772-Oct. 17, 1836); the first Hannah ( 1774-1774; lived three months); Hannah (1777-1873); Polly (1779-1859); and Ebenezer (1783-1876)

Abraham, Jr., was born in Ipswich in 1759; married Abigail Norris, of Whitefield; and died April 12, 1837. Lowden called him “a prominent citizen of Whitefield.”

According to the on-line genealogy, Aaron was born in Ipswich. On Dec. 20, 1788, in Pownal, he married Elizabeth Acorn of Waldoborough (born about 1770, died in 1844). Before moving to Windsor, they lived in Whitefield, where Lowden said Choate ran the mill his father bought into.

They must have moved while Windsor was still Waterford Plantation, because Aaron Choate is one of those who petitioned to have it incorporated as a town in January 1808.

(Lowden pointed out that the petitioners clearly asked the Massachusetts legislature to name their town Alpha, but the legislation that was approved called it Malta. He explained the change as “the slip of a clerk’s pen.”)

Aaron and Elizabeth had five sons and five daughters, born between 1789 and 1807 (or later), the genealogy says. According to both the genealogy (whose writer used the phrase “It is said”) and Lowden, it was Aaron Choate’s land that Paul Chadwick was surveying when he was murdered by settlers on Sept. 8, 1809, and Choate witnessed the murder.

Elizabeth reportedly died in Windsor, Aaron, in China.

Lowden listed their second son, Aaron, Jr. (May 17, 1792- June 21, 1874), among 13 men who bought pews when the Congregationalists and the Freewill Baptists built the Union Church (aka the North Meetinghouse) in 1827 on Windsor Neck.

Abraham, Jr., and Aaron’s younger brother, Rufus Lathrop, spent “part of his youth” with his uncle in Norwich, Connecticut, Lowden wrote. Kingsbury said he moved to Windsor Neck about 1812.

In Connecticut, he married Elizabeth “Betsey” Maynard. Find a Grave shows their double headstone in the Hallowell Village cemetery; the website says she was born in 1785 and died March 18, 1863, and gives his birthdate as Feb. 18, not Feb. 28, 1772.

Lowden’s list of Windsor men who served briefly in the War of 1812 (mentioned last week) includes private Rufus Choate.

In the mid-1830s, Washington Choate and Thomas Choate (Lowden did not explain where they fit into the family – Aaron’s nephews, perhaps?) were briefly part-owners of a mill on a dam across the west branch of the Sheepscot near the confluence with Dearborn Brook. The dam caused the river and brook to back up onto land owned by 20 people Lowden listed, including Aaron Choate.

Lowden called the Choates one of Windsor’s “five basic families” (the others were the Hallowells, Merrills, Pierces and Sprouls), who were the ancestors of “almost all native residents” when he wrote his history in 1993. In addition to the family members mentioned above, readers may remember from previous articles in this series that he often cited the diary of Orren Choate (June 20, 1868-1948).

Sheepscot River

A 2018 article on the history of the Sheepscot River by Arlene Cole, Newcastle historian and weather recorder, includes a description of its course to the Atlantic Ocean.

Cole wrote that the western branch begins in a swamp in southern Albion and goes through Palermo, where the dam at Branch Mills backs up its flow to form Branch Pond; China, including Weeks Mills Village; Windsor; and Whitefield.

The eastern branch, which Cole called Turner Brook, starts in Palermo, she wrote; the deLorme atlas shows branches from Palermo and Liberty joining, detouring into Montville and returning to Palermo. Trending southwest through Sheepscot Pond, this stream passes through Somerville and joins the west branch south of the village of Coopers Mills in Whitefield.

Cole said this junction marks the beginning of the true Sheepscot River. Above, she wrote, the west branch is 21 miles long and the east branch 14.5 miles long. Below, the river runs another 34 miles to the Atlantic.

Your writer found on line three explanations for the name that has become “Sheepscot.”

One was proposed in 1869 by Rev. Edward Ballard, of Brunswick (then secretary of the Maine Historical Society), as part of a list of Geographical Names on the Maine Coast reprinted in the appendix to an undated national coast survey.

Ballard divided the name into three parts from the Etchemnin (or Etchemin, a subdivision of Algonquian) language: “seep,” which he said means a bird; “sis,” meaning little; and “cot,” meaning place or location. He combined them to mean “Little-bird-place,” and wrote that each year “at the proper season” Maine Natives harvested young ducks on the river.

Cole said the name was Abnaki (Abenaki), another branch of Algonquian. Originally it was Pahsheapsakook, she wrote. She quoted Fanny Hardy Eckstorm’s division – “pahshe” means divided; “apak” means rocks; “ook” means water place or channels – and concluded the name means the place where “the river is split up into many rocky channels.”

A third source, Alfred L. Meister, in the introduction to an undated report on Atlantic salmon in the river, said James Davis of the Popham Colony (1607-1608 in what is now Phippsburg) called the river the Pashipakokee, and other early historians (whom Meister did not name) called it the Aponey or Aponeag. Meister said early fisheries included alewives, salmon and shad.

Main sources

Kingsbury Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Lowden, Linwood H., good Land & fine Contrey but Poor roads a history of Windsor, Maine (1993).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Responsible journalism is hard work!

It is also expensive!

If you enjoy reading The Town Line and the good news we bring you each week, would you consider a donation to help us continue the work we’re doing?

The Town Line is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit private foundation, and all donations are tax deductible under the Internal Revenue Service code.

To help, please visit our online donation page or mail a check payable to The Town Line, PO Box 89, South China, ME 04358. Your contribution is appreciated!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!