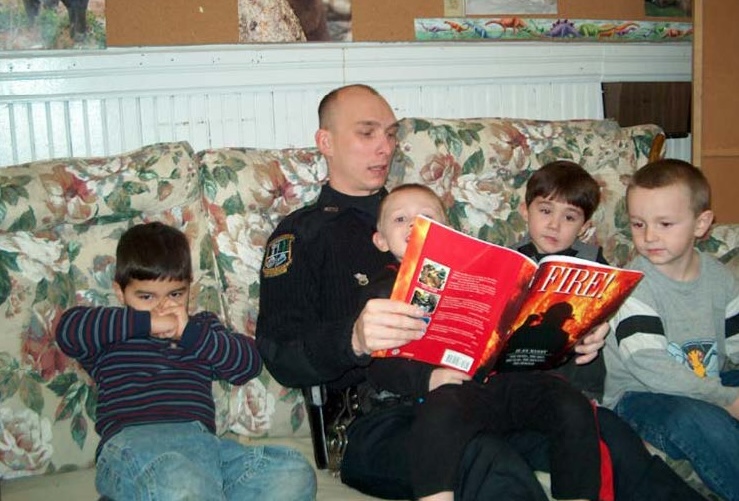

Waterville City Hall and Opera House.

This article will return to the history of a series of buildings, more cheerful than the Augusta jail(s) described in the June 5 story: Waterville’s town hall that became a city hall that was – and still is – combined with a large gathering space called an opera house.

As with the public buildings in Augusta, there are gaps and inconsistencies in the information. A small part of the problem is nomenclature. Winslow and its meeting places were on the east bank of the Kennebec; on the west bank after 1802, Waterville had two meeting houses, the one near the river called the Ticonic or east meeting house and the one farther inland called the west meeting house.

Readers may remember that Waterville became a separate town from Winslow, divided physically by the Kennebec River and legally by the Massachusetts legislature, on June 23, 1802. According to both Henry Kingsbury, in his 1892 Kennebec County history, and Rev. Edwin Carey Whittemore, in his 1902 Waterville centennial history, the earliest meeting house on the west (future Waterville) shore predated the division.

Whittemore found the first reference to a Winslow meeting house in records of a Feb. 10, 1794, town meeting, held in a private home. Voters approved building a meeting house, for both religious and secular purposes, on land on the east (Winslow) bank of the Kennebec that Arthur Lithgow would donate; and raised 100 pounds to build it.

Later in 1794, Winslow voters invited a minister to town. Rev. Joshua Cushman, a Revolutionary War veteran and Harvard graduate, came and stayed 20 years.

He apparently didn’t have a building for the first couple years. Whittemore said on March 7 and 8, 1796, voters first authorized building a meeting house “on the hill near or in Ticonic village,” on the west bank; and then “voted to build another on the Lithgow lot in Winslow, the previous vote concerning it having been reconsidered.”

A five-man “committee for the west side” reported on March 16, 1796, recommending putting up the west (future Waterville) building and selling pews. “Such was the beginning of the meeting house which is now a part of the old city hall,” Whittemore wrote in 1902.

Once the meeting house was approved, Whittemore said, Dr. Obadiah Williams “offered…the present city hall park” for that building and also a schoolhouse or courthouse. A petition from the town’s western residents for a more central location was denied.

Waterville’s present city hall faces south across Castonguay Square. The square is on the north side of Common Street, which runs east-west for the block between Main and Front streets.

On-line information says the land was deeded to Waterville in 1840 and known as The Commons until 1921, when it was renamed to honor Arthur L. Castonguay, the first Waterville soldier killed in action during World War I.

Although the meeting house wasn’t finished for years, Whittemore said the first west side (of the Kennebec) town meeting was held there June 25, 1798. Kingsbury wrote, “The town meeting house on the west side was built in 1797, and first used March 5, 1798.”

Having an unbridged river dividing the body politic was an obvious inconvenience to voters on both sides trying to exercise their democratic rights. On Dec. 28, 1801, Winslow voters petitioned the Massachusetts legislature to create a new town on the west side of the river; and on June 23, 1802, Waterville was incorporated.

The first Waterville town meeting was in the Ticonic or east meeting house on Monday, July 26, 1802. The main business was electing town officials.

Winslow, from 1771, and Waterville, in 1802, included most of what is now Oakland, known after 1802 as West Waterville. Kingsbury wrote that before 1802, a second meeting house was being planned in that area (again, no location is specified).

The legislative act that created Waterville provided that money “assessed for building a meeting house in the West Pond settlement shall be paid and exclusively appropriated to that purpose”; Winslow was not to have any of it.

The west meeting house must have been finished, or almost, by August 1802, because Whittemore said Waterville’s second town meeting was held there on Aug. 9, 1802; and Kingsbury said voters that month approved holding future meetings alternately between the two.

In 1807 or 1808, as war with Great Britain appeared a possibility, Whittemore wrote that voters approved building a “powder magazine in the loft of the meeting house, probably as the driest place available.” Presumably he meant the east meeting house. That the building was also a church is shown by his reference to a preacher’s salary in the same sentence.

Whittemore mentioned the meeting hall again when part of the July 4, 1826, celebration was held there. Then, without explanation, he wrote that in 1842, “the old east meeting house was moved back and fitted up for a town hall.”

The “town hall” was the site of a June 3, 1854, anti-slavery meeting and of at least two gatherings in response to the Civil War.

On April 20, 1861, Whittemore wrote, a large meeting to respond to the April 12 attack on Fort Sumter was held in “the old town hall.” It led immediately to the organization of companies of volunteers.

On March 14, 1864, the “old town hall” was the site of a concert to start raising money for a monument honoring Civil War soldiers. Martin Milmore’s bronze statue of the “Citizen Soldier” was dedicated in Monument Park on May 30, 1876.

The western part of Waterville, with its meeting house, separated on Feb. 26, 1873. The new town was West Waterville for a decade before becoming Oakland.

In his chapter on Oakland, Kingsbury wrote that the “town meeting house” built by Winslow officials “about 1800” “was used for religious and other public gatherings and for town meetings till 1841, when it was taken down.” In 1892, the town hall was Memorial Hall, an 1870 brick and stone building on Church Street that honors Oakland’s Civil War soldiers.

Waterville’s 1874 Independence Day celebration included “a grand dinner in the town hall.” In 1875, Whittemore wrote “a new town hall was proposed”; he did not say by whom, or why. Instead, town officials spent $5,000 to add 33 feet to the existing building.

After rejecting a city charter approved by the Maine legislature in 1884, on Jan. 23, 1888, Waterville voters adopted an amended charter, by a vote of 543 in favor to 432 opposed. The town became a city, with the same municipal building.

In the spring of 1896, Whittemore wrote, an undetermined number of unidentified voters asked for a May 18 meeting, apparently to debate a single question that he quoted as: “to see if the voters of the city will instruct the city council to build a city hall and opera house this season.”

Whittemore thought the idea reasonable. By then, the “old city hall, the east meetinghouse of 1796, with sundry remodellings, was no longer on a plane with the dignity or the demands of the city,” in his opinion.

He did not explain why petitioners included an opera house.

A “largely attended” public meeting was held on May 18, 1896, to ask if voters wanted the city council to build “a city hall and opera house.” A majority said yes, please, estimating the cost at $75,000.

On May 4, 1897, there was another vote: 526 voters approved creating a City Building Commission, while 404 dissented. Consequently, Whittemore wrote, “Plans were accepted, the old hall was moved back, contracts were signed and the foundation of the new hall was partly laid.”

Then the “conservative or as some said reactionary” faction got an injunction that stopped work.

Nothing more was done until early 1901, when more public meetings led the city council to order work resumed, to be financed through taxes over following years, with the cost estimated at $70,000.

The architect for the building was George D. Adams, from Lawrence, Massachusetts. The new city hall was dedicated during the centennial celebration, on the morning of June 23, 1902, “the city’s birthday.” William Abbott Smith’s description of the ceremony in Whittemore’s history referred to “expressions of satisfaction which came from the vast throng that visited every corner of the new building.”

The ceremony, held in the new Opera House, included music, speeches and a presentation of the keys to the building by contractor Horace Purinton to Mayor Martin Blaisdell.

Purinton commented on the range of sources for building materials: stone from northern New York and Michigan, terra cotta from New Jersey clay, brick from local clay, wood from Maine, Georgia and Indiana.

Whittemore’s account praised Purinton and Blaisdell. Abbott added words of appreciation for former Waterville Board of Trade president Frank Redington, who presided over the dedication ceremony.

In his opening remarks, Redington called the new building “a suitable home for our city officials,” and its “convention hall” a meeting place for public discussion, “the old town house remodelled, enlarged, beautified, adorned, and fulfilled.”

He continued: “Some of you are perhaps thinking of the entertainment element which is introduced, for the human mind is so constructed that it needs entertainment as much as the body needs nourishment.”

Whittemore concluded his account of the building: “Waterville at last has a city hall of which she may well be proud.”

Waterville City Hall has been on the National Register of Historic Places since Jan. 1, 1976. In their October 1975 application for a listing, Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., and Frank A. Beard, of the Maine Historic Preservation Commission, described the building as “a good representative example of the multi-purpose civic buildings erected in Maine at the turn of the century.”

It stands three stories tall, with a stone foundation and basement and the upper stories “brick with wood and stone trim.” The main entrance to the city offices is in the center of the south façade; stone steps lead up to both sides of a recessed doorway under an arch, with arched windows on either side.

Above the entrance, three more arched windows are separated by white columns, with elaborate brickwork across the whole front. Top-floor windows are very small. Shettleworth and Beard wrote that the top of the front of the building “is completed by an elaborate wooden cornice composed of a dentil molding, a series of modillions and an ornamental crest at the center bearing the inscription ‘City Hall’.”

The entrance to the opera house/auditorium is on the west side, which Shettleworth and Beard described as handsomely decorated.

Inside, city offices occupy the basement and first floor. The top of the building is taken up by the auditorium, its lobby and backstage area.

Shettleworth and Beard found that the auditorium was called “Assembly Rooms”; “one of its earliest uses was for a dairyman’s exhibition.” It hosted varied touring entertainments, including, the historians said, Australian actress Judith Anderson; American singer Rudy Vallee; American opera singer and civil rights leader Marian Anderson; and early American Western movie actor Tom Mix, whose horse had “to be hauled up the outside of the building” to join him on stage.

After World War II the auditorium was used as a movie theater. It has always provided a venue for local entertainments.

Main sources

Kingsbury, Henry D., ed., Illustrated History of Kennebec County Maine 1625-1892 (1892).

Whittemore, Rev. Edwin Carey, Centennial History of Waterville 1802-1902 (1902).

Websites, miscellaneous.

Type O blood donors especially urged to give

Type O blood donors especially urged to give

A total 707 of undergraduate students at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), in Worcester, Massachusetts, completed research-driven, professional-level projects that apply science and technology to address an important societal need or issue.

A total 707 of undergraduate students at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), in Worcester, Massachusetts, completed research-driven, professional-level projects that apply science and technology to address an important societal need or issue.