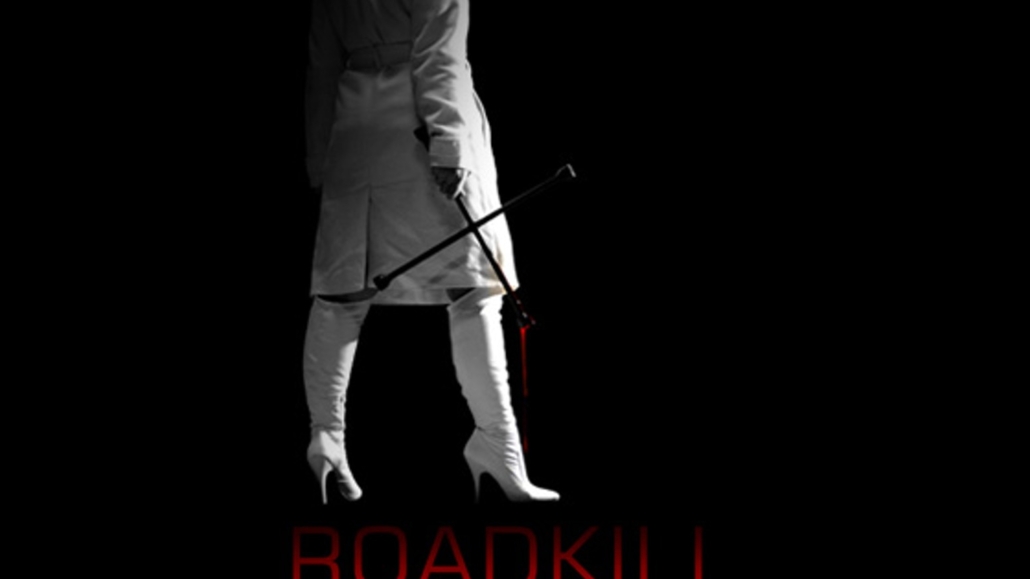

Road Kill: A Love Story

starring Erika Hoveland, Brandon Culp, Cain Perry etc.; available for free viewing on Amazon Prime; directed by Raphael Maria Buechel; 2014.

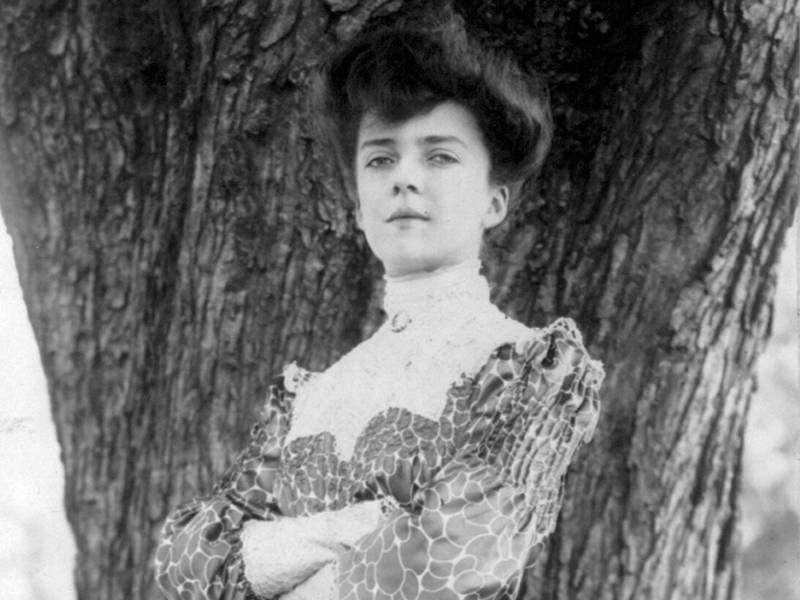

Erika Hoveland

The movie Road Kill: A Love Story, was completed by 2014 but took until this year to achieve world wide distribution.

It stars Brandon Culp as the mute Mitch who works in a small town car wash; Erika Hoveland as Taryn who moves into the village to open a taxidermy shop, and has a hunger for true love along with a huge thirst for blood; and Cain Perry as Mitch’s brother, Joe, who’s also the local sheriff, an alcoholic drinking too often on the job parked by the side of the road in a squad car, talks often to Madge the dispatcher (their dialog providing some of the funnier moments in the film) and has a girlfriend who’s a psychiatrist.

Strikingly interesting opening scenes include a man stuck at night on the side of the road with his broken down car, a truck pulling up with a woman driving it and ambiguity as to whether or not help has arrived. Then daylight ensues with Mitch arriving at the car wash and having a practical joke played on him by his co-workers. The fast food joint across the street has three women employees who seem to be goofing off, one of them developing a growing attraction to Mitch while her colleagues urge her to do something about it. Neither establishment is doing much business – just another lazy day in a small town on a hot summer day.

Taryn drives up to the car wash in a pickup truck and recruits Mitch for some heavy lifting back at her address. Needless to say, the film keeps getting more interesting; at this point, I refuse to provide any more spoilers, commend everyone who was involved in the film down to the tiniest detail, and, noting a certain resemblance to the American gothic style of the Coen brothers, applaud its otherwise superlative individuality.

A 5 star viewing experience!

Two more films:

Frozen Ground

starring Nicholas Cage, John Cusack and Vanessa Hudgens; 2013 and available on Netflix.

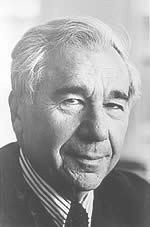

Nicolas Cage

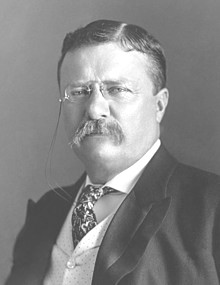

John Cusack

Frozen Ground is based on the true story of Alaska serial killer Robert Hansen and the joint collaboration of an investigator and one woman who escaped being murdered by him while in captivity. It was a well-done suspense film; two qualities in particular stood out: driving around in a winter blizzard after nightfall, which make winters in Maine seem like a summer picnic, and the woman’s close encounter with a mild-mannered bull moose on a city street.

Vanessa Hudgens

Seven Deaths of Maria Callas

starring Marina Abramovic and Willem Dafoe; available online for free viewing until October 7.

The Seven Deaths of Maria Callas was seen live earlier this month at the Bavarian State Opera House, in Munich, Germany, and by myself and others around the world on-line after several months of delays, mainly due to the coronavirus pandemic. It was the fruit of a 60-year fascination with operatic soprano Maria Callas (1923-1977) that began when performance artist/actress/director Marina Abramovic first heard the singer on her grandmother’s kitchen radio at her farm in Yugoslavia.

She read, studied, listened to and absorbed every last detail on the singer’s art and life. She identified her own obsessions with those of her idol in which life and art become one and the same and at risk to one’s health and life (the wikipedia pieces on both women are good places to start for more about them.).

The play features Abramovic portraying Callas moving around the stage and on her deathbed, and Willem Dafoe as a stalking lover/adversary. Callas was quite famous for her brilliant singing/acting of death scenes from operas by Bellini, Bizet, Donizetti, Puccini and Verdi and a different soprano and actress performs each one. Abramovic’s voice is heard commenting on life, love, art, death etc. on tape while neither she nor Dafoe are ever seen speaking.

One of the arias, Un Bel Di (One Fine Day) is from Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, which takes place in early 1900’s Nagasaki, Japan. In light of what happened there and at Hiroshima in early August 1945, figures in hazmat suits are moving around while that aria is being sung.

At the conclusion of Seven Deaths, Callas’s own recording of the Bellini aria is heard.

Marko Nikodijevic composed incidental music for the production while Yoel Gamzou conducted the orchestra.

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates