REVIEW POTPOURRI – Movie: Dog; Christmas music; Quotable quotes

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Dog

Movies portraying the love of man’s best friend have been melting the hearts of cynics since the days of Lassie Come Home. Another perspective was achieved in this past February’s release, Dog.

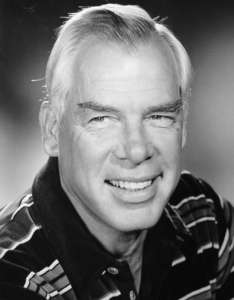

Channing Tatum portrays Briggs, a former army Ranger who has been removed from combat due to some brain damage. Unable to adjust to civilian life, he wants reinstatement and, after constant nagging of his superior officer, is finally given an opportunity to prove himself worthy.

A fellow Ranger, Rodriguez, has been killed in an automobile accident and his burial with full military honors takes place in five days in Nogales, Arizona, itself 1,500 miles from where Briggs lives near Tacoma, Washington.

Briggs is asked to escort Rodriguez’s service dog, a very aggressive Belgian Malinois named Lulu, as a tribute to her handler. Afterwards Briggs will take the dog to the nearby White Sands base to be euthanized. Only then will he be reinstated.

Despite being crated and muzzled, the dog destroys the inside of Briggs’ van. Other incidents include Lulu being released from the vehicle by an overzealous animal rights activist, while Briggs is elsewhere, who believes the canine is being mistreated, but who then is attacked by Lulu.

The dog again escapes from the car later in Oregon and leads Briggs to a marijuana farm. Its owner, Gus, shoots a tranquilizing dart in Briggs, believing him to be an intruder, ties him up but then sees reason when his wife Tamara has a calming influence on both Briggs and Lulu.

(Here, I commend the seasoned acting of Kevin Nash and Jane Adams as the married couple.).

Inevitably Briggs and Lulu begin to bond, as other obstacles, and even a few epiphanies, occur during the remainder of their journey. At this point, I simply recommend this film for the manner in which this potentially hackneyed plot is developed in a strikingly unusual manner, with a message of hope and redemption.

The film was produced at a cost of $15 million and, since its release, raked in $85 million.

A charming Christmas album

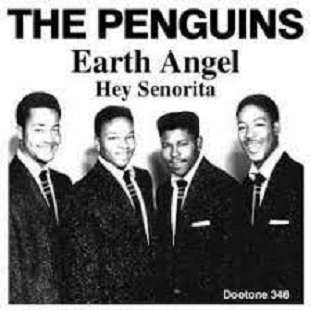

A very charming 1959 LP on the Dot label, Merry Christmas, features the Mills Brothers applying their unique harmonizing to 12 yuletide favorites; the six on side one include such secular examples as Gene Autry’s Here Comes Santa Claus, Irving Berlin’s White Christmas, and one of the finest renditions of Mel Torme’s perennially delectable Christmas Song, surpassed only by a tiny margin by the one of Percy Faith’s orchestra and ladies chorus, while the second side contains the traditional Xmas carols.

And the album can be heard on YouTube.

Quotable quote

December 3 was the 165th birthday of the great novelist Joseph Conrad (1857-1924). I offer one of his very pertinent quotes:

“It is only those who do nothing who make no mistakes, I suppose.”