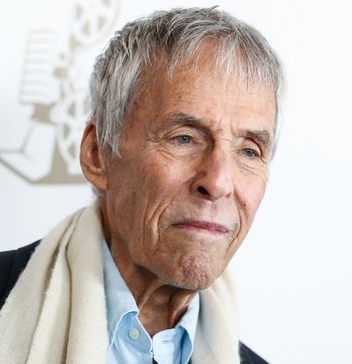

REVIEW POTPOURRI: Scottish conductor, Sir Alexander Gibson

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Alex

by Conrad Wilson; Mainstream Publishing, 1993, 159 pages.

Conrad Wilson

This biography has a special fascination because Alex and I were good friends during the early ‘80s – Alex being the late Scottish conductor, Sir Alexander Gibson (1926-1995), whose recordings, guest appearances and 25 years as music director of both the Scottish National Orchestra and the Scottish Opera brought him international fame. It was the kind of fame justly deserved through hard work, consistently high quality results, discipline, passion for music and good will towards those he worked with. He was both a great conductor, a fine human being and a gracious friend. And he practiced humility – qualities rare among ego-driven conductors.

I saw him conduct several concerts in Houston featuring works of Bach, Beethoven, Schumann, Mozart, Liszt, Brahms, Elgar, Holst, Mahler, Berlioz, Saint-Saens and Szymanowski. And lots of Sibelius. He didn’t have the clearest beat but he and the players felt it together. I felt that every performance was conducted as if it would be his last, a quality surprisingly less frequent among other certain shining stars of the firmnament.

Sir Alexander Gibson

I own many of his records and CDs, all of them at least very good. Click his name on Amazon for numerous listings, each one highly recommended.

The book recounts his various successes with so many opera productions, especially Puccini; the many concerts featuring Sibelius, the names recounted earlier, and numerous world premieres; and his gifts as both organist and pianist during his early years. He was adept in managing emergencies during actual concerts and productions. Finally, no other conductor in history matches his length of service with an opera house and orchestra at the same time!

I also remember him as a chain smoker but, by the ‘90s, he had quit.

In January 1995, he died from unexpected complications following surgery.

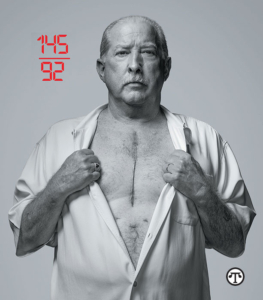

(NAPSI)—High blood pressure is often silent—showing no signs or symptoms—but it’s not invisible. Survivors are speaking out to show the real impact of high blood pressure, and a new campaign from the Ad Council, American Heart Association and American Medical Association provides resources to help you and your doctor create a treatment plan that works for you.

(NAPSI)—High blood pressure is often silent—showing no signs or symptoms—but it’s not invisible. Survivors are speaking out to show the real impact of high blood pressure, and a new campaign from the Ad Council, American Heart Association and American Medical Association provides resources to help you and your doctor create a treatment plan that works for you. Understanding High Blood Pressure

Understanding High Blood Pressure

These procedures are called “Vascularized Composite Allograft” organ transplants, or VCA transplants. They are composed of multiple types of tissue. With a hand transplant, for example, bones, blood vessels, nerves and skin must all be attached to the remaining arm.

These procedures are called “Vascularized Composite Allograft” organ transplants, or VCA transplants. They are composed of multiple types of tissue. With a hand transplant, for example, bones, blood vessels, nerves and skin must all be attached to the remaining arm.