REVIEW POTPOURRI: Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Symphony

by Peter Cates

by Peter Cates

Rachmaninoff’s 2nd Symphony

After the failure of his 1st Symphony in 1897, Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) had a nervous breakdown that lasted three years, with a loss of confidence in himself as a composer. Relief finally came when he submitted to three months of hypnosis under the supervision of Dr. Nicolai Dahl. His revived creative juices brought the hugely successful 2nd Piano Concerto.

In 1904, he assumed the position of conductor at the Bolshoi Opera House. However 1905 brought increased waves of revolutionary activities in Russia following the massacre by Czarist troops of many protesters at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg; Rachmaninoff himself cared little about politics and found the unrest distracting to his work .

He resigned from the Bolshoi in 1906 after starting work on his 2nd Symphony and moved himself and his family to Dresden, Germany, for four years, while spending summers at his in-laws’ estate in Ivanovka, Russia (that estate was 3,500 miles east of Dresden and made for a long railway round trip.). Both Dresden and Ivanovka gave the peace he needed to compose several works, such as the Isle of the Dead, his 3rd Piano Concerto and the 1st Piano Sonata. But his need to support his family necessitated a concert tour of the United States in 1909 and a prolonged separation from his wife.

The 2nd Symphony was a huge success at its 1908 world premiere in St. Petersburg and a boon to his self-esteem. It is almost 60 minutes and was often performed with cuts until 50 years ago when the complete score became the norm. As the composer did with the 2nd Piano Concerto, he poured his emotions into the Symphony and created a masterfully developed panorama of delectable melody.

It consists of four movements – the soaring Largo/Allegro moderato, a rip-roaring Scherzo, the sweet Adagio and the triumphant Allegro vivace. My first experience of it occurred during my high school sophomore year when I heard the 1959 Columbia LP of Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra (It was the Philadelphia Orchestra that gave the U.S. premiere of the symphony under the composer’s direction during his 1909 American tour and, during the ‘20s and ‘30s, Rachmaninoff recorded several works with the Orchestra as pianist with his friends, former Music Directors Leopold Stokowski and Stokowski’s successor, Eugene Ormandy, of the four Piano Concertos and Paganini Rhapsody and himself conducted 78 record sets of his 3rd Symphony and Isle of the Dead.)

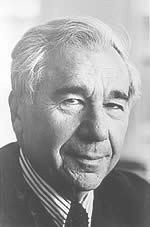

A YouTube video of a 1979 performance with Ormandy, then 80, and the Philadelphians is one of the most captivating examples of a great conductor at work. Ormandy left two other recordings of the symphony, one from the early 1930s with the Minneapolis Orchestra and a 1973 one. Other distinguished ones from as early as 1928 through recent years are those of another close friend of the composer Nicolai Sokoloff, Artur Rodzinski, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Alfred Wallenstein, Kurt Sanderling, William Steinberg, Andre Previn, Yuri Temirkanov, Paul Kletzki, Gennady Rozhdestvensky, Leonard Slatkin, Simon Rattle, Alexander Gibson, Walter Weller, Lorin Maazel, James Loughran, Adrian Boult,Vladimir Ashkenazy, Edo De Waart, Tadaaki Otaka, Yevgeni Svetlanov, Andrew Litton, Mariss Jansons, Antonio Pappano, etc., the symphony being music that generates conductors’ best efforts.

Despite his extraordinary gifts as a pianist and conductor, Rachmaninoff was happiest when engaged in composition.